Columns

Legendary sportsman Leslie Claudius is a champion without ego, writes Raju Mukherji

In India, our Olympic victories are few and far between. But at the same time, we have had a legendary sportsman who won four Olympic medals and then lost all of them! No riddle this. It actually happened.

For an Indian to win four Olympic medallions, he had to be a hockey player because India dominated world hockey from 1928 to the 1960s. Your guess that the sport is hockey is as perfect as it can be. But can you guess the name of the player concerned?

It happened to be none other than Leslie Claudius, the hockey marvel who won three gold medals and one silver for India in the four Olympics between 1948 and 1960.

Olympic medallists are honoured and revered world over. To win an Olympic medal is an awesome achievement. These champions are a rare breed. But then to win four is nothing short of a miracle. Very, very few international sportsmen have won four Olympic medals and more.

Also, not many international sportsmen have lost their Olympic medals! The legendary ‘American Black’ boxer Muhammad Ali (then Cassius Clay) threw away his gold medal out of sheer disgust. But that is another story for another time.

Indeed, Leslie Claudius is the only international sportsman known to have lost all the medals he had won at the Olympics—thanks to an odd-job man who had come to his house to polish his medals and trophies. Unfortunately, the man actually polished off the medals and vanished without leaving behind any trace!

As a freelancer, when I went to Leslie Claudius’s residence for an interview for the Tiger Pataudi-edited sports weekly Sportsworld way back in the 1980s, the laid-back personality quite casually said, “Ah! You want to see the Olympic medals? I had asked a man to clean and polish my trophies. He took me literally, I suppose. He took the money and the medals with him. However he did a very good job with the rest of the trophies in the cabinet.”

I was aghast, “Did you actually keep those gold and silver medals in an unlocked showcase in the drawing room?” He nodded, “My mistake, I reckon. But then why would anybody be interested in my trophies?” When told the medals would fetch millions as souvenirs among collectors, he gave a relaxed smile, “Let’s say he needed the money more than I did!” It took a little while to dawn on the interviewer that the phlegmatic individual sitting opposite was in a sphere of his own without any attachment to worldly objects.

The life of Leslie Claudius has always been full of such unusual happenings. Born and brought up in hockey-dominated Bilaspur in Madhya Pradesh, the young Claudius was fascinated by football and was fantastic at it. Among the sports fanatic Anglo- Indian community at Bilaspur, he was an all-round sportsman with particular fondness for football.

Yet, when he came over to football-mad Bengal, first to Kharagpur and from there to Calcutta in 1946, football ironically receded into the background as the game of hockey dribbled into his heart. Office teams like Port Commissioners and Calcutta Customs helped him with opportunities and his latent talent flowered in next to no time.

At every level—office, club and State teams—he left his mark. It is indeed unbelievable that in only two years since he seriously wielded a hockey stick for the first time, he was donning the national colours in the London Olympics in 1948. With Dhyan Chand and company around, India had won the Olympic hockey gold in Amsterdam (1928), Los Angeles (1932) and Berlin (1936). Because of World War II, no Olympics took place in 1940 and 1944. In fact, the 1948 London Olympics would be the first time Independent India would play under her own national tricolour.

There was considerable consternation among hockey followers. Would India be able to put up a reasonably good show with not much hockey played during the war period? Would the new players be able to live up to the high expectations? Did we still possess the required talent? But by the end of the London Olympics, the Indian flag kept fluttering to remind us of the exploits of Dhyan Chand, Rup Singh, Richard Allen, Carlyle Tapsell, Eric Pinniger and company. Untried youngsters like Claudius, Keshav Dutt, Ranganathan Francis and Randhir Singh Gentle came to the fore in 1948 and gave relief to hockey lovers around the country. In 1952 Udham Singh and Balbir Singh (Sr) arrived. India’s top stature in world hockey remained unscathed.

From 1948, Leslie Claudius was India’s mainstay at the pivotal position of centre-half for the next 12 years. This was the continuation of the golden period of Indian hockey. Uninterrupted success was a mere formality. Legendary Indian players dominated the world in a style as distinctive as it was effective. Claudius was always in focal point as the sheet anchor. One moment he would be defending his own goal, the next he would be threatening the opposition’s ‘D’. Energetic and selfless, he had indomitable courage and will power to overcome any opposition, situation and condition.

Leslie Claudius was a stylist who combined impeccable technique with powers of innovation. He inspired not by hollow words of advice but solid performance. He had no time for provincial, communal or class bias. He had no time for unscrupulous administrators. He formed no group, joined none. He was the shining nucleus of a world champion team.

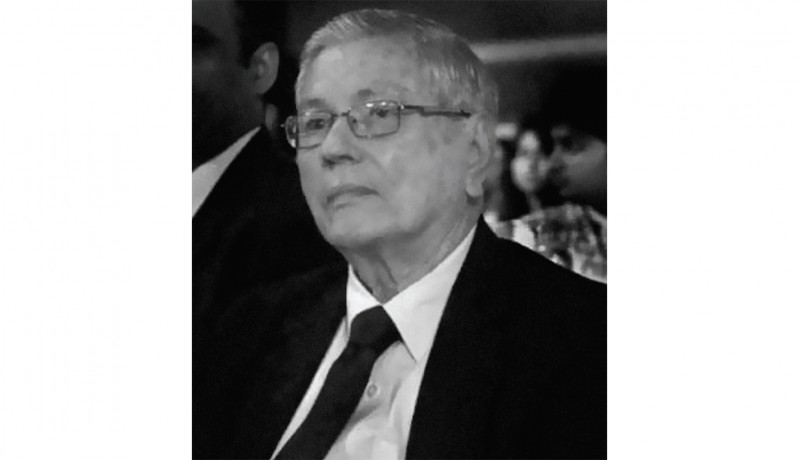

But the contradictions continued. He was of medium height, very tough but not muscular. He was not an exhibitionist. On the contrary, he was a clean-shaven, young man of exemplary manners and bright eyes. His refreshing charm, modesty, refined voice and conduct belied all the conventional impressions of a star sportsman. He was a champion without an ego. He was an artist without any hangups. He was a superstar without controversy following him. He was a magnificent centre-half without having anyone good enough to be his rightful protégé.

A delightful conversationalist, he once said, “We were unlucky not to have seen Dhyan Chand and Roop Singh at their peak. But let me tell you, son, even in their old age such was their ball control that we had difficulty in taking the ball away from them. Both were wizards with the stick in hand. Roop was no less than his brother Dhyan, but was destined to be forever in the shadow of his elder brother.”

During the course of the interview at his McLeod Road flat, Claudius said, “From the 1950s, many Anglo-Indians left India to settle in Australia and Canada. This was a setback for Indian hockey as the Anglo-Indians showed a distinct flair for the stick and ball game.” Absolutely correct he was. Many of our past greats came from the Anglo-Indian community.

After three successive Olympic gold medals in London (1948), Helsinki (1952) and Melbourne (1956), Claudius was selected to lead the country at the Rome Olympic Games in 1960. This was his 4th Olympics. Later in 1964, Udham Singh, too, repeated Claudius’s record of three golds and one silver.

Sadly, India’s domination of the Olympic hockey honours came to an end in the final against Pakistan. Claudius was shattered. For him, the silver medal was no compensation. He bid adieu to the game he loved and served with the greatest of dignity. “That was the saddest day of my life,” he recounted. “It was a magnificent final against Pakistan in Rome. No quarters were given and none expected. But the one-nil defeat was just too much for me. I retired on our return.” Furrowed eyebrows clouded his face.

Within moments, however, he brightened up, “You know, son, when the national flag goes up the pole you get a strange feeling that cannot be described. Hardened men have tears in their eyes. You only think of your country and nothing else matters. I was lucky to have enjoyed that exhilarating feeling no less than three times.” Then, his voice faltered, “On the podium in Rome, we tried to muffle our disappointment. Tough adults cried like children. The silver medal seemed to mock me.”

Sport is said to be a great leveller. Claudius is an exception to the rule. For he has had no failures. Yet the man himself felt he had failed the country in Rome. Such were his high standards that even the silver medal was considered a failure!

But no, most certainly he did not fail. Rather he was a glorious example of an ideal champion: charming, modest and selfless apart from being a magical wielder of the hockey wand. The memory of the dignified self still remains a shining model for every aspiring sportsman.

Kolkata-based Mukherji is a former cricket player, coach, selector, talent scout, match referee and writer

Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine August 2018

you may also like to read

-

Mental workout

Mukul Sharma tells you how to keep those grey cells ticking Everyone will ultimately lose his or her brain….

-

Helpline

Dr Harshbir Rana answers your queries on personal and social issues related to ageing, elder care and intergenerational relationships ….

-

Off the cuff

Raju Mukherji pays tribute to his first hero, Tenzing Norgay, an exemplary mountaineer Darjeeling, 1955. Dr ‘Pahari’ Guha Mazumdar….

-

Yoga RX

Shameem Akthar shows ways to control debilitating ankle pain through regular practice Ankle pain is so common and prevalent….