Columns

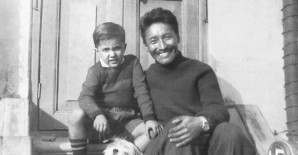

Raju Mukherji remembers Tulemaran Aao and Neville D’Souza, the unsung heroes of football

The sorry tale of Indian football is best exemplified by the incidents concerning Tulemaran Aao and Neville D’Souza. Aao was India’s first captain at the Olympic Games in 1948. Neville D’Souza was India’s sole hat-trick maker at the Olympic Games in 1956. Both possessed impeccable credentials as footballers, but both suffered irreparable neglect.

Tulemaran Aao was from Kohima in Nagaland. He was a brilliant scholar and had come down to Calcutta after India’s Independence in 1947. While chatting with his fellow students at the campus of Calcutta Medical College, he came to know football was a very popular sport among the local Bengalees.

He told his mates he would like to go to the ground one day to witness a match. A doctor-to-be student friend of his accompanied Tulemaran to the Mohun Bagan-East Bengal ground on the northern periphery of Fort William at the Calcutta maidan. It is said that Aao observed the match in progress with very keen interest. Later, with much trepidation, he asked his friend if a trial could be organised for him at one of the clubs. As it transpired, another student knew a patron of East Bengal Club, K D Banerjee, who called Aao over to the club for a trial. He arrived early at the ground with his kit bag in tow.

A group of footballers were about to start their practice session. Aao quickly changed into his football gear and joined them. The coach happened to be Balaidas Chatterjee, a very influential sports administrator who had been a prominent football player and boxer in his salad days. Balaidas realised he had found a gem and, without any delay, registered him to play for the club. However, without realising it, Aao had joined the rival club Mohun Bagan whereas he was supposed to attend the East Bengal trial! As both teams shared the same ground, it was not possible for the young Naga student to know which club was practising at the time. When K D Banerjee arrived at the ground with the East Bengal team for practice, Aao was taken aback. But KD put his arm around Aao and told him, “Son, do not worry. You have got a club. Be loyal to it. Make a name for yourself.” How prophetic those words were to be!

At the time, Mohun Bagan officials prided themselves in not recruiting foreign talent. They relied on Indians and took special care of their players. Normally, a player who joined the club would become a family member of the club, as it were. Aao fitted into the slot with ease and his academic credentials added to his ready acceptance at the club.

Within the course of the year, the bright medical student became the club’s most prominent player in deep defence. He was tough and fearless in his tackles and looked every inch the ideal sportsman. In 1948, when it was announced that the Indian football team would take part in the Olympic Games for the first time as an independent nation, the name of the medical student from Kohima was right on top as captain. At the Games in London, the Indian players played superb football, only to go down 1-2 against France. India failed to convert two penalty kicks and was knocked out of the tournament after just one outing.

Back home, Aao could see that times were changing. Corruption and intrigue were gradually filtering in at the Calcutta maidan. Now in his final year, the medical student did not want to waste time with maidan politics and, sensibly, bid adieu to Mohun Bagan and football forever. He went back to Kohima and became a popular and successful medical practitioner. The intelligent gentleman kept himself away from the wretched condition of Indian football. For their part, our football administrators had no time for India’s former captain and an outstanding defender because he did not come from the mainstream states.

As for Indian football, after a disastrous experience at the Helsinki Olympics in 1952 where the team lost 1-10 to Yugoslavia, it was in doldrums. As directed by FIFA, Indian players were now forced to wear boots— unlike in London in 1948 where they were allowed to play barefoot—and tried their best to adopt and adapt. Thankfully, a magnificent batch of youngsters arrived on the scene at the same time. In coach Rahim they found a mentor who could inspire and encourage.

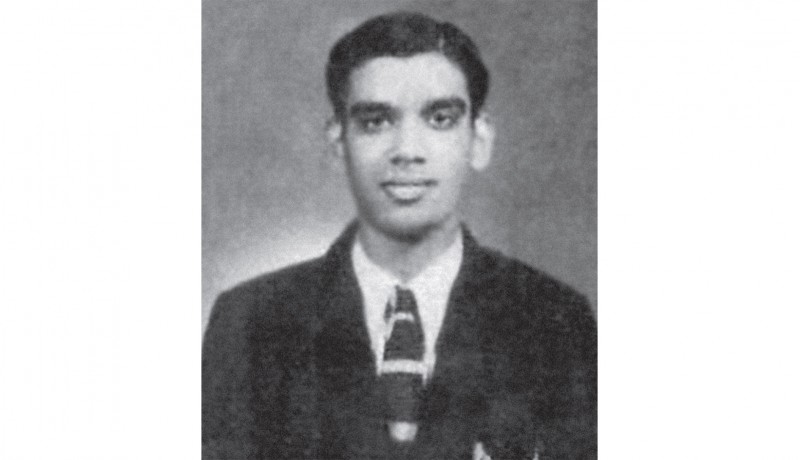

And at the Melbourne Olympics in 1956, Indian football players made the nation proud—they missed the bronze medal but came in fourth. The principal torchbearers included youngsters like Tulsidas Balaram from Andhra Pradesh, P K Banerjee from Bengal, Narayan from Bombay, and Neville Stephen D’Souza from Goa, which was a Portuguese colony in India at the time.

Among these prodigious talents, the man who was in the headlines perpetually was D’Souza. He could weave his way through hardened defenders with courage and gumption—and then unleash a thunderbolt of a shot that blasted the net. D’Souza possessed firepower in his feet and his power and unerring accuracy would find the back of the net from any angle. He was a centre-forward who had no weakness as a striker. Whether shooting or heading, he had few parallels. He sent the international football critics into raptures with a brilliant hat-trick against Australia. (He later scored India’s only goal in a losing cause against Yugoslavia.) Never again was any Indian able to replicate this outstanding feat at the Olympics.

However, the bug of corruption Aao had anticipated in the late 1940s was already in motion. When the trials for the selection of the Indian team for the following Olympics in Rome in 1960 were in progress, it was a foregone conclusion that D’Souza would be the captain. He had all the essential qualities of leadership. Apart from being among the best players, he was by far the most articulate and had a brilliant, incisive, tactical mind. He had even led Maharashtra to victory in the Santosh Trophy, the symbol of inter-state supremacy in Indian soccer. But, sad to relate, D’Souza was not only deprived of the captaincy, he was omitted from the team altogether! He then vanished from the Indian football scenario for ever.

Why would this happen? You see, D’Souza was educated and held prominent positions in multinational corporations. It seems his supposedly ‘better’ background went against him! The general conception among football administrators in India was that the players should belong to financially deprived sections; should not have any decent academic credentials; and should kowtow to officials and be happy to receive whatever little they were offered. Unfortunately, the attitude has not changed much even after so many years.

Neville D’Souza was not a person who would bow down to undeserving people. He had education, self-respect and a brilliant career with a MNC ahead of him. He would be the last person to dance to the tunes of corrupt, unworthy officialdom. For all his sterling qualities, he was forced to make way for the less deserving. Thankfully, like his famous Naga predecessor Tulemaran Aao, the Goan D’Souza never compromised; never resorted to underhand dealings; never formed cliques; never flattered influential officials; never conspired to win awards. They played and lived their successful lives with their head held high.

Kolkata-based Mukherji is a former cricket player, coach, selector, talent scout, match referee and writer

Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine October 2018

you may also like to read

-

Mental workout

Mukul Sharma tells you how to keep those grey cells ticking Everyone will ultimately lose his or her brain….

-

Helpline

Dr Harshbir Rana answers your queries on personal and social issues related to ageing, elder care and intergenerational relationships ….

-

Off the cuff

Raju Mukherji pays tribute to his first hero, Tenzing Norgay, an exemplary mountaineer Darjeeling, 1955. Dr ‘Pahari’ Guha Mazumdar….

-

Yoga RX

Shameem Akthar shows ways to control debilitating ankle pain through regular practice Ankle pain is so common and prevalent….