Columns

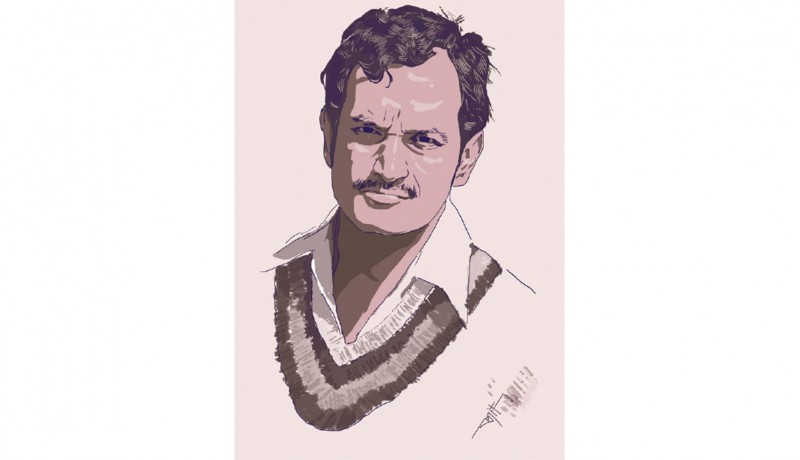

Raju Mukherji pays tribute to one of India’s greatest cricket captains Ajit Wadekar

Only thrice has India won a Test series on English soil. The captains were Ajit Wadekar (1971), Kapil Dev (1986) and Rahul Dravid (2007). Ironically, not one of the above three has ever been rated very highly as a captain in India. In fact, captains who lost or drew the series in England have been eulogised in the Indian media! Cricket history reveals that the England tour is always the most difficult for Indians. Since 1932, India has played 17 Test series on English soil and lost 13 of them. Most Indian captains who lost or drew have been those who were supposed to possess exceptional cricket brains.

Yet, the exceptional achievements of the three successful Indian captains in England have not received their due recognition. Superb leaders of men like Ajit Wadekar, Kapil Dev and Rahul Dravid never received any acclaim for their leadership qualities. Very strange, indeed. And very unfortunate.

Wadekar’s captaincy career was a giant wheel in motion. For a period of three years, he was right on top, having won every series that came his way. Then, in a matter of weeks in 1974, he came crashing down. He became a villain whom everybody wanted to curse and kick.

People forgot that he had won a series against West Indies in their backyard in 1971, and repeated his success in England against a very strong team in 1971. The following season, in 1972-73, his team beat England in India. Australia had just beaten England. So if there was a system of ranking at the time, India would have been the top cricketing nation in the world in 1972. Thus, Wadekar won three series in succession, a feat no other Indian captain has ever been able to replicate. He was indeed unlucky that he never had Zimbabwe and Bangladesh in the opposition.

Wadekar received almost no credit for his team’s success. It was always claimed that he won with ‘Tiger Pataudi’s men’! Till the last day of his life, he maintained, “If that were the issue, why did Tiger not win with his own men?” Absolutely to the point.

However, in 1974, Wadekar’s team lost all its three Tests in England. It was a disastrous tour for India with all the top stars available. The moment that happened, his house in Mumbai became the target of stones and bricks. Ajit Wadekar actually had almost the same players as he did in 1974. Yet the media forgot all about ‘Tiger Pataudi’s men’ and laid all the blame on Wadekar’s captaincy! Disappointed and upset, Wadekar retired immediately from all forms of cricket on his return from England in 1974.

There is a notion in India that Indian cricket came of age in 1983 when the Prudential World Cup was won in England. Actually, huge amounts of money began to flow into Indian cricket since 1983 on account of the great achievement of Kapil Dev and his men. In reality, Indian cricket began to get the respect of the oppositions from 1971. That particular year was the turning point of Indian cricket in more ways than one. Except in one series, in 1968-69, Indian cricketers had always been on the losing end on overseas tours ever since their inaugural tour of England in 1932.

In 1968-69 Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi’s men won a series abroad for the first time. The opponents were the weak New Zealanders. No one took the Kiwis seriously at the time. In fact, along with New Zealand, teams from India and Pakistan were considered weak oppositions away from home. After having experimented with a host of potential talents for about two years, in 1971 the chairman of the national selection committee Vijay Merchant—among the best-ever openers—omitted Pataudi from the captaincy saddle. This was major ‘news’ at the time. The obvious choice was his deputy Chandu Borde. He, too, was dropped. A studious, reticent young man by the name of Ajit Wadekar was elevated to the post amid much accusation of provincial bias.

But Merchant stuck to his ideas. He brought in young people with outstanding performance in domestic cricket. Merchant had no time for ‘fancy players’ with supposed potential and no performance. All those who were tried and had failed to perform during those two seasons were gently sidelined.

Thus, Ajit Wadekar was fortunate that he had the ‘grey matter’ of Merchant to guide him. He was selected as captain because he had led Bombay and West Zone to innumerable victories in domestic cricket. He knew what leadership was all about and, very important, knew how to win.

Surprisingly, Wadekar never played serious cricket while at school. He was a very bright student and had once even maxed his algebra paper. While a school student, his cricket was restricted to casual matches with his neighbourhood peers. In college, his cricket suddenly flowered and he became a regular in the strong Bombay University side.

At the time, he was a fluent player of exceptional elegance. His stylish stroke play was a connoisseur’s delight. Drives and cuts came naturally to him. He joined Shivaji Park Gymkhana, one of the bastions of Marathi cricketers in Bombay. There, he honed his skills under the careful guidance of various former cricketers, as is the custom in Mumbai even today.

Wadekar was not satisfied in being stylish alone. He developed a gluttony for runs and more runs. No amount of high scores would satisfy his appetite. This approach stayed with him in every domestic championship. He would ‘murder’ spin bowling under any conditions. High-rising deliveries of extreme pace troubled him. But then who did not have problems against such deliveries? As the great Rohan Kanhai, among the greatest of ‘hookers’, once said, “None of us like 90 mph deliveries coming to our face; it is only that some play them better than others.”

Unfortunately, Wadekar was ignored for a long time by the national selectors. Finally, when he could not be neglected any more by the sheer weight of his performances, he made his debut in 1967 in his late 20s. But, by then, his style had changed beyond belief. He was no longer the fluid stroke maker of yore. His approach was of a man who had come to make the most of his limited opportunities. He was very effective, no doubt, but no longer the graceful striker he had been.

Wadekar led from the front. He taught us that we were good enough to beat the best in the world by our own methods. He did not copy others. Did not bother to find out what Australia, England and West Indies were doing. He concentrated on India’s strength. He relied on spin bowling and on close-in catching to win matches for India.

Wadekar selected his XI on the basis of ‘horses for courses’. The moment the genius of Salim Durani gave India the victory at Port of Spain, skipper Wadekar’s total concentration was to hold on to the lead till the last day of the series. In England, too, at the Oval he realised that if anybody could give India a victory, it would be Bhagawat Chandrasekhar. He had Chandra to plunge the dagger in and hold on till the opposition submitted. Wadekar had a set of the most brilliant foursome around the batters to accept even catches that could hardly be rated as chances. Men like Eknath Solkar, Venkataraghavan, Abid Ali and he formed a quartet that was the best-ever close-in cordon the world had ever seen.

People who criticise Wadekar conveniently forget that he did not possess a single pace bowler worth mentioning. He had a wicketkeeper who was more of a showman. Apart from the young Viswanath and the younger Gavaskar, skipper Ajit Wadekar never possessed another batter of world renown. He fought the best with very limited talent. But the brilliant man got his mix in the right proportion. He taught India that we could beat the best in their own backyard. Today, it may not appear to be a difficult task, but back in the 1970s it was a yeoman effort. None thought it could be achieved. When it did happen, our media was so servile that instead of praising Wadekar and his boys, they began to say that the opposition was weak!

Ajit Wadekar never played to the gallery. He made no friends with the media for support, never compromised on his tough approach. He kept his wit for his after-dinner speeches. He preferred the company of books to the company of flatterers at the bar. An everlasting memory of Wadekar was at the Moin-ud-Dowlah Trophy championship at Hyderabad in the early 1970s. While most players would be at the lounge on the first floor of the Fateh Maidan’s Lal Bahadur Shastri Stadium, nursing their drinks, the India skipper would be seen in his room with a book and beer for company. He evinced a keen interest in the book I was reading. He borrowed it and returned it within two days mentioning, “I am a fan of Che Guevara as well.”

The next time I met him was in his chamber at a nationalised bank in Mumbai. He was the sports convenor of the Banks’ Sports Board. As the representative from Calcutta, I asked him if it would be possible to have observers sent to the neglected northeast of India to unearth sports talent. Wadekar kept his ears open and gave his assent.

Some banks carried out the directive very diligently. One of the discoveries happened to be a teenager from Sikkim, Bhaichung Bhutia. Actually, it was a former football player from Wadekar’s bank, Bhaskar Ganguly, who can be given the credit for the discovery.

Kolkata-based Mukherji is a former cricket player, coach, selector, talent scout, match referee and writer

Illustration by Jit Ray Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine November 2018

you may also like to read

-

Mental workout

Mukul Sharma tells you how to keep those grey cells ticking Everyone will ultimately lose his or her brain….

-

Helpline

Dr Harshbir Rana answers your queries on personal and social issues related to ageing, elder care and intergenerational relationships ….

-

Off the cuff

Raju Mukherji pays tribute to his first hero, Tenzing Norgay, an exemplary mountaineer Darjeeling, 1955. Dr ‘Pahari’ Guha Mazumdar….

-

Yoga RX

Shameem Akthar shows ways to control debilitating ankle pain through regular practice Ankle pain is so common and prevalent….