Health

With nearly 500,000 Indians dying every year waiting for a transplant, organ donation is an imperative today, overcoming the paucity of infrastructure, lack of awareness and outdated mindsets. Analysing government policies and gathering perspectives from experts, stakeholders and families, Sahil Jaswal looks at how far we’ve come—and how much further we have to go

On 5 July 2018, the city of Mumbai saw its 27th cadaver donation of the year and its 92nd heart transplant since August 2015. Dr Anvay Mulay, head of the cardiac transplant team at Fortis Hospital, Mulund, successfully harvested a heart from a 40 year-old donor, a resident of Thane, who succumbed to injuries from a road traffic accident and was pronounced brain dead—the heart was transplanted into a 55 year-old male recipient from Surat.

THE NUMBER CRUNCH

It was another significant milestone in a larger mission: the promotion of organ donation. Every year, nearly 500,000 Indians die because of non-availability of organs—an estimated 200,000 people die of liver disease, 50,000 people die from heart disease and 150,000 people await a kidney transplant, while 1 million people with corneal blindness await a transplant. Indeed, India has an abysmally low rate of 0.86 persons as organ donors per million population—a paltry number by global standards.

Thus, every donation, every successful transplant, is cause for cheer. Consider the fact that up until 2008, Maharashtra had not conducted even one successful heart transplant, as we reported in our feature “Donating Lives” (May 2008). The tide turned only in August 2015, when Fortis Hospital, Mulund, successfully transplanted a heart into a 22 year-old graphic designer. The heart was flown in from Pune; overcoming the organisational challenges, Mumbai Police created a green corridor and delivered the heart to Mulund, 20 km from the airport, during peak hours, taking one-fifth of the usual time. That year, Maharashtra successfully transplanted five hearts; 2016 saw 47 heart transplants from the state.

Our 2008 report also noted the fact that liver transplant activity was still in its infancy in India—the number of transplants till May 2007 was just 342 in the entire country. Fortunately, the situation has improved. In 2016, there were 108 liver transplants in

Maharashtra alone; across India, there were 665 liver transplants from deceased donors, up from 523 in 2015 and 354 in 2014.

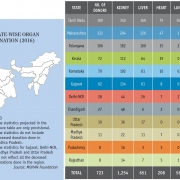

According to data from the National Organ and Tissue Transplant Organisation (NOTTO), in 2017, Tamil Nadu saw 176 cadaver donations of which 318 kidneys, 152 livers, 112 hearts and 87 lungs were transplanted, while Kerala had 26 cadaver donations, of which 46 kidneys, 19 liver and eight hearts were transplanted, and Chandigarh saw 44 cadaver donors, with 121 organs successfully transplanted. In Maharashtra, there were 170 cadaver donations compared to 142 in 2016, serving up 503 organs for end-stage organ failure patients. Of the 170 cadavers, 57 came from Mumbai and saved nearly 350 end-stage organ failure patients, marking the organ donation rate at 2.34, comparable to leading states like Tamil Nadu at 2.56. This year, 2018, up until 8 June, Maharashtra has had 57 cadaver donations, from which a total of 763 organs and tissues have been utilised.

UNDERSTANDING ORGAN DONATION

It’s clear that organ donation is imperative in India today. But first, it’s important to understand the process. Organ donation is when a person allows an organ to be removed, legally, to gift to another person with end-stage organ disease. It is done either by consent while the donor is alive or after death with the assent of the next of kin.

LIVE ORGAN DONATION

As the name suggests, live organ donation takes place when a person is alive. Individuals of 18 or above can donate their organs and tissues either to ‘near relatives’ or out of affection to others. Near relatives, according to the Transplantation of Human Organs Act (THOA) 1994, refers to parents, children, sister and spouse, but the Act was amended in 2011 to include grandparents and grandchildren. While the Act allows donors to donate out of affection or any other special reason, the process is quite stringent and has to go through the local and, if necessary, the state authorisation committee to curb organ trafficking. A living donor can donate a kidney or a part of the liver.

Significantly, 85 per cent of liver donors in India are live donors. Take, for instance, 55 year-old Anita Sathe, who was diagnosed with cirrhosis in 2011. Further damage was limited through heavy medications. However, in December 2017, her condition worsened and a liver transplant became unavoidable. “The doctors told us that we could either wait for a cadaveric donation, which could have taken at least a year, or somebody from the family could donate,” shares Anita. Luckily, the family stepped up—her 28 year-old daughter Anuja’s liver matched perfectly. “We were told by the doctors that the liver regenerates, so I was ready to help my mother,” she says. In February 2018, a part of Anuja’s liver was sliced and transplanted into her mother at Mumbai’s Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani Hospital (KDAH). Six months hence, both mother and daughter are in the pink of health, although Anita is still being monitored monthly.

“A recipient is monitored weekly for the first month, every second week for three months and then monthly,” says Dr Ashutosh Chauhan, liver transplant and hepato-pancreatobiliary (HPB) surgeon at Mumbai’s Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani Hospital (KDAH). “The donor is released in five to six days with painkillers and has to come for only one follow-up after seven to 10 days.” He adds that a transplant is done only for end-stage liver disease. “Cirrhosis, where scar tissue replaces normal tissue, is the most common reason why adults need liver transplants. Hepatitis B and C, where the liver swells up, cancer and metabolic disorders, if unchecked, are other reasons that make a transplant imperative.”

SWAP DONATIONS

Swap donations are also live donations, but for families that don’t have the same blood group. For example, a husband, incompatible to donate his kidney or liver for his wife, can donate for a stranger of another family, provided anyone related to the stranger does the same for his wife. Cases of swap donation were included in the Transplant of Human Organs and Tissues (THOT) Act 2014 in an attempt to increase the donor pool. The Act stated that swap donations shall be approved by the authorisation committee of the hospital district or state and are permissible only through near relatives.

However, medical advancements, at least in the case of kidney transplants, have made the concept of swap donations less relevant. “Blood group and tissue match were the criteria for kidney transplant, but at Kokilaben Hospital we have overcome these two hurdles,” says Dr Sharad Seth, head of nephrology at KDAH. “So even if there is a mismatch, the results are successful.” In addition, Rekha Barot, transplant coordinator at KDAH, shares, “Seventy-five per cent of live donors are women. They are either trying to save their husband, children or other family members.”

DECEASED ORGAN DONATION

Deceased organ donation is the aim of donor pledges, and how organ donation rates are determined. Anyone regardless of age, race or gender can become an organ and tissue donor after they have been declared either brain dead or deceased from cardiorespiratory death (circulatory death), unless they suffer from malignancies like cancer, infections like HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C, and diseases like tuberculosis. In India, after death, the consent of a near relative or a person in lawful possession of the body is required before the organs can be retrieved.

DONATION AFTER BRAIN DEATH (DBD)

Donation after brain death is when a deceased person’s family consents to donate their organs to another patient suffering from end-stage organ disease. Brain death is permanent cessation of all functions of the brain—while individual organs may function, there is lack of the brain’s integrating functionality and loss of respiration, consciousness and cognition that confirms death as an irreversible condition. DBD was legalised in 1994 under THOA; the same year, in August, Dr P Venugopal, head of the cardiothoracic centre in Delhi’s All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), carried out a successful heart transplant. After brain death, almost 37 different organs and tissues can be donated, including vital organs such as kidneys, heart, liver and lungs.

A PRECIOUS GIFT

In Mumbai, businessman Chimanlal Sawla, 52, was pronounced brain dead on 17 January 2018—his two kidneys, eyes, liver and heart were donated. “The doctors and the transplant coordinator of KDAH had asked us if we would like to donate his organs,” shares his son Jignesh. “The family agreed unanimously as we knew he would be giving others the most precious gift of life.”

Mumbaikar Nirmala Nandu, 65, knows just how precious it is. Diagnosed with cirrhosis in 2013, she registered for a donation in 2015 through several hospitals. “Almost a year went by waiting for a donor,” she recalls. “When it became unbearable, my daughter got her tests done and turned out to be a match. However, at the last minute a liver was made available from Indore.” The transplant was done in November 2016; two years on, Nandu is back to her household routine.

Indeed, the list of people awaiting transplants is woefully long across the country. In June 2018, in Mumbai alone, 3,000 people were awaiting a kidney transplant, 250 to 300 a liver transplant, and 10 to 15 a heart transplant.

In January 2016, 35 year-old Rubina, another resident of Mumbai, was told her heart’s functions were limited to 10-15 per cent. In March 2016, she registered through KDAH; on 26 June 2016, she underwent transplant surgery. “A transplant becomes imperative when a patient reaches terminal heart failure, which is also called ‘Stage D’,” explains Dr Nandkishore Kapadia, director of heart and lung transplant at KDAH. “In the US, 500,000 patients are suffering from heart failure; in India the number is 2.7 million. India is the diabetic capital of the world, so there are more incidents of heart failure.” Here, he makes an interesting point: “Despite the rise in terminal heart failure, Mumbai has only 10-15 on the waiting list because most patients are referred late. Either the patient doesn’t want to accept that they are heading towards Stage D heart failure or the treating doctor is unaware they have a potential transplant patient. So I would say, at least Mumbai is not lacking in donors, but recipients.”

Evidently, it is not only paucity of donors but a lack of infrastructure and awareness that is leading to the needless loss of life. Exacerbating the problem is an archaic mindset guided by superstition.

GROWING INFRASTRUCTURE

In a report published in journal Neurology India, Dr Aneesh Srivastava of the department of urology and renal transplantation, Sanjay Gandhi Post-Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow, writes, “The total organ donation shortage of the country can be met if 5-10 per cent of victims involved in fatal accidents serve as organ donors.” But here’s the rub: lack of infrastructure.

As Dr Vimal Bhandari, director of NOTTO, explains, “Over 1.5 lakh people die every year in road traffic accidents. And it is true that in almost 30-40 per cent of fatalities, the cause of the death has been head injury, leading to brain death. However, in such cases, the patient is admitted to public hospitals and the majority have not applied for retrieval and transplant license.”

Consider the fact that while there are over 160 government medical colleges in India, only a handful are licensed to be retrieval and transplant centres. According to the NOTTO website, there are a total of 231 transplant and retrieval centres across India, both public and private.

In this scenario, Tamil Nadu stands tall as an example to follow—with 103 transplant centres in place, its organ donation rate, at 2.56, is the highest in India. According to data available with State Health and Family Welfare Department under the Deceased Donor Organ Transplant Programme, a total of 6,481 organ donations have been undertaken in the state from October 2008 to May 2018. In March 2015, the Transplant Authority of Tamil Nadu (TRANSTAN) was created to coordinate and supervise transplant activities (including live, cadaver and tissue transplants). And while private hospitals still continue to be largest contributors of cadavers to the programme, the state offers free kidney, liver and heart transplants in government hospitals. Maharashtra is also making strides with a total of 86 organ transplant centres and 42 non-transplant organ retrieval centres (NTORC). Mumbai and Pune both have 36 transplant centres, as of April 2018.

Other states, unfortunately, tell a different story. Eastern India is the worst, with most states not having conducted cadaver donations at all, along with Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh and Jammu & Kashmir. “The need of the hour is to get infrastructure in place,” says Lalitha Raghuram, country director of the Multi Organ Harvesting and Aid Network (MOHAN) Foundation, a not-for-profit organisation promoting organ donation and transplantation since 1997. Raghuram who has also served as executive director of the Eye Bank Association of India (1993-2002), further adds, “Assam as of now has only five retrieval and transplant centres, and Gujarat has around 12 [according to MOHAN Foundation], while Telangana has 26.”

To achieve greater success, both the public and private sectors need to come together. Take civic-run King Edward Memorial (KEM) Hospital in Mumbai, for instance. This is where the Regional Organ and Tissue Transplant Organisation (ROTTO) for the Western Zone has been set up; yet, it only received its heart retrieval and transplant license in May 2018. “It’s the private sector that is leading the charge,” affirms Dr Ashutosh Chauhan of KDAH. “But the overall rate will become better if the government sector also joins hands.”

COMBATING POLITICAL APATHY

“Organ donation is a public health issue,” says Dr Ram Narain, executive director of KDAH. Indeed, the Deceased Donor Organ Transplant Programme is run at state level. The steps to create awareness about organ donations, including promoting public understanding of brain death, networking between hospitals and protocols for allocation, come under the state’s purview. And all states do not follow the same protocol.

In many states, there is no government body to monitor (or hold accountable for) proceedings in an organ transplant case. Gujarat is one such state with no organ donation policy in place, although it has 12 kidney retrieval centres and two heart retrieval centres—Care Institute of Medical Sciences (CIMS) and Sterling Hospital, both private, both in Ahmedabad. Recently, ROTTO Maharashtra, which administers the Western India zone, refused to accept any organs from Gujarat till it frames a policy and forms a State Organ and Tissue Transplant Organisation (SOTTO).

Again, Tamil Nadu forms a stark contrast with its centralised waiting list and streamlined procedures to declare brain death. Hospitals work in conjunction with the state government, which has made it compulsory for all hospitals to report cases of brain-dead patients, enabling it to identify and retrieve organs from potential donors. It also permits relatives of organ donors to get priority in organ transplant, as long as the hospital certifies the relationship. The state also conducts workshops to educate and sensitise medical professionals from across the state on deceased donation.

Hearteningly, others have taken a cue. In 2015, Union Surface and Transport and Shipping Minister (and Nagpur MP) Nitin Gadkari, along with Nagpur Mayor Pravin Datke and Rajya Sabha member Ajay Sancheti pledged their organs. In fact, Gadkari has been instrumental in proposing to incorporate organ donation information on the driving license, nationally. Also, Maharashtra Medical Education Minister Girish Mahajan took the lead in starting an online registry for organ donations in August 2016; during his tenure, the number of donation centres in the state increased from three to 17 (four civic-run and 13 state medical colleges) and organ donation has been adopted as a flagship programme of the state government.

What’s more, this June, the Indian Union Health Ministry recommended that state health departments offer ‘cash rewards’ for organ donation. The jury’s still out on that one, though, as many experts contend that commercialisation of such an altruistic act would deter people to avoid the stigma of having ‘sold’ the organs of their loved ones and give rise to organ trafficking, no matter how stringent the processes to gauge the motives of a donation. Instead, they argue that incentives should be non-monetary, as is the case in Israel.

RAISING AWARENESS

Political will aside, lack of awareness is a major bugbear.

Priyanka Borah would agree. The CEO of Zublee Foundation, the first NGO working for cadaver donation awareness in the Northeast, she says, “Lack of awareness among the medical fraternity tops the list of impediments in the programme, followed by lack of awareness among the masses. With infrastructure at a very nascent stage, no proper medical training and lackadaisical networking between hospitals, things are far from getting better.” Dr Bhandari of NOTTO adds, “Many government hospitals don’t have a clear protocol for declaring brain death; even the medical community sometimes are at a loss, so they don’t come forward and inform the authorities of the potential donor.”

Many brain death cases occur in public hospitals where declaration of brain death is negligible. In fact, there have been innumerable cases where patients are declared brain dead but are either kept on a ventilator or just taken off it because attendants don’t understand the process of organ donation. And with the medical fraternity unaware, family members also find themselves in the dark for options in case of a death.

“Brain death is a difficult concept to wrap their head around for most families,” says Bhavana Chabbria of Shatayu Foundation, an Ahmedabad-based public-service initiative by Govindbhai C Patel Foundation. “Even though there are no chances of resuscitation, a brain-dead person is still warm and pink and most families can’t come to terms that their loved one has passed away. This is where awareness among the masses and the medical fraternity plays a major role in increasing the donor pool. Correspondence by transplant coordinators over the matter is another step to educate the families of potential donors and probably save many lives.”

Metropolitan cities seem to be doing better. “The masses are surprisingly aware now, through countless initiatives and campaigns by various organisations,” says Raghuram of MOHAN Foundation. “They understand that organ donation is a vital service to humanity.” Concurring with her, Rekha Barot of KDAH says, “Lack of awareness among donors hasn’t played much of a role in dearth of organs available, at least in metros. In my personal experience, a family does not agree to donate only when the sentiments attached are extremely overwhelming. Once we explain the deed they are doing and that a brain-dead patient can save at least eight lives, almost everyone agrees to be a donor. And this is true for all classes, educated or uneducated.”

Mumbaikar Reema Joseph, 36, has been the recipient of this generosity. After suffering kidney failure in 2013, she started dialysis in 2015 but her condition continued to worsen. She finally registered through KDAH in October 2017. “I got a match within four months but I rejected the kidney as my family was travelling and I could not make that decision alone,” she reveals. “But as luck would have it, another kidney was made available to me and on 14 February 2018, I underwent surgery.”

Maharashtra Medical Education Minister Mahajan reiterated this point at the CSR Corporate Meet held on 8 June 2018 by The Times of India in association with KDAH. But he cautioned, “Though there is greater awareness… we should not think the battle is won. There is still a set of people that believes in outrageous and outdated theories. For instance, ‘If I donate now, in my next birth I will be born without those organs’. Such beliefs can be eradicated only by educating the masses.”

ACTS OF FAITH

Religious beliefs do play a significant role in the low consent rates seen in India. This has been cause for concern even in UK and their government is trying to address this.

With this in mind, a key component of the organ donation awareness initiative by KDAH and The Times of India, now in its sixth year, is a myth-busting session where religious leaders from various communities set the record straight on the subject.

“People have their own individual beliefs about the next life, but as per the scriptures there is no mention of organ donation being an impediment towards it,” says Swami Shridurgananda, a representative of Ramakrishna Mission in Mumbai.

“What we carry in the next life are the pancha tanmatra [perceptions/subtle elements]: sabda tanmatra is the sound vibration, sparsa tanmatra is touch, rupa tanmatra is form, rasa tanmatra is flavour and gandha tanmatra is smell.”

Father Stephen Fernandes, professor of moral theology at Mumbai’s St Pius College, also assures us that the church does not have anything against the act of organ donation. In fact, in August 2000, Pope John Paul II had addressed the 18th International Congress of Transplant Society in Rome, where he called organ donation “a boon for humanity”, if done in an ethical manner.

In Islam, there is a concept called sadqah-e-jariyah, which means continued or ongoing charity, which comes to benefit people even after the person who made the donation has passed away. A number of Fiqh (Islamic law) academies, such as the Islamic Fiqh Assembly of the Muslim World League in Jeddah, have opined that organ donation is permissible to save a person’s life.

“The fact that our body accepts organs from another’s is because our body has been naturally made this way,” reasons Maria Khan of the Centre for Peace and Spirituality, an organisation that shares the spiritual principles of Islam with the world. “It is natural law. If organ donation was unnatural, it would not have been possible for us to donate in the first place. Some Muslims may argue that organ donation is like muthla or disfigurement, which is unlawful in Islam. But drawing this parallel is completely wrong. Muthla always involves extremely bad intentions in terms of humiliation, while organ donation is entirely an act of good intention. It is done with the best of wishes for fellow human beings and the deceased donor from whom the organs are retrieved is treated with respect and honour.”

Interestingly, in his writings, Swami Sukhabodhananda references the Bhagavad-Gita where Lord Krishna says, “Tad viddhi pranipaatena pariprashnena sevaya.” [Be humble, bow down and enquire with a sense of seva.] “Organ donation is the uttama seva, which is the highest service, giving life to another human being,” the spiritual master explains. “Seva is the pathway that helps us go beyond the body and mind.”

CAN YOU DONATE?

This seva, this pathway is yours to take—if you so choose. Too many people mistakenly assume their age precludes them from organ donation, but this is false. Organ donation can be done regardless of age, race or gender, and people as old as 80 and beyond have the potential to save lives by donating their organs. Significantly, even people who suffer from malignancies, infections and diseases can save lives in their own way: though their organs cannot be harvested for therapeutic purposes, they can be donated to medical colleges for research, for educating budding doctors in transplant procedures and raising awareness among the medical fraternity.

Sharing her experience of donating her father’s body to medical science, Arati Menon, editor of Harmony- Celebrate Age, says “My father S Sundararajan passed away on 29 December 2013 at AIIMS, New Delhi. As he was suffering from cancer, he couldn’t donate his organs but he was adamant all along that we donate his cadaver.” Unlike organ donation, body donation precludes the possibility of performing last rites as the body is given to the medical college/hospital. “The decision was difficult for my mother, as his next of kin, to make, as she is quite religious,” she adds. “But she didn’t overrule his wishes because she knew how important it was to him. Today, as a family, we are very much at peace with the decision, and very proud.”

Ultimately, much of it does boil down to family, the need to have frank conversations about organ donation, especially as consent from next of kin is mandatory in India. If convinced, ensure you convince those around you. While our government works to get a more effective national transplant programme up and running with proper interstate organ transfers and efficient networking between hospitals, it’s time for us, on an individual level, to draw from our own well of compassion and answer the call. Each one of us has the power to save lives—let’s use it.

ALL YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT ORGAN DONATION

OPEN TO ALL: Anyone can register to be an organ donor, regardless of age, race or medical history. That includes you.

CARE COMES FIRST: Your donation status will not affect the medical care you receive. The first priority of medical professionals is always to save lives.

LIVE AND LET LIVE: A ‘living donor’ can also save lives by donating a kidney or part of the liver.

REST ASSURED: Organ donation does not become an option until brain death has been declared.

NO COSTS: Organ donation does not have any cost or financial implications for donors or their families.

ACT OF FAITH: All major religions support organ donation and view it as a final act of love and generosity.

DONOR’S DIGNITY: Donors and their families are treated with care, respect and dignity throughout the process.

RESPECT YOUR RITES: Last rites are possible for organ donors. There are no visible deformities.

GLOBAL LESSONS

THE TOP 5 (in per million population/pmp)

- Spain – 46.9 pmp

- Portugal – 34.0 pmp

- Belgium – 33.6 pmp

- Croatia – 33.0 pmp

- USA – 32.0 pmp

SOURCE: International Registry in Organ Donation and Transplantation, 2017

- In 1989, the Spanish government invested heavily in the organisational structure of organ donation, ensuring every hospital in the country had its own organ donation coordinator. It also addressed the family consent rate by adopting a long contact method where coordinators identify potential donors early (using clinical triggers) and spend a considerable amount of time getting to know the family of the potential donor.

- In 1991, the Surgeon General of the United States introduced new legislation in the US Federal Register mandating that each hospital had a legal duty to identify and refer every potential donor to the Organ Donor Organisation.

- In 2011, the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) appointed Gurch Randhawa, a professor of diversity in public health, to help overcome religious and community objections to organ donation through campaigns, surveys and seminars.

- In 2012, Israel introduced a scheme, nicknamed ‘Don’t Give, Don’t Get’, where priority is offered for transplants to living donors and their family members, along with health and life insurance, for up to five years and complete reimbursements to live donors. The transplant rate shot up by 60 per cent within the first year of implementation.

INDIAN MILESTONES

- 1968: Dr P K Sen performed India’s first heart transplant procedure at Mumbai’s King Edward Memorial Hospital (KEM).

- 1994: The primary legislation regarding organ donation and transplantation, Transplantation of Human Organs Act (THOA) was passed in 1994.

- 1994: Brain death was legalised; on 3 August, Dr P Venugopal, head of the cardiothoracic centre at AIIMS, Delhi, performed India’s first successful heart transplant.

- 1994: According to THOA 1994, hospitals had to register for a license to engage in removal, storage or transplantation of human organs.

- 2011: Provision of non-transplant organ retrieval centres (NTORC) for retrieval of organs from deceased donors and their registration under amended Act; THOA amendment included tissue donation and registration of tissue banks.

- 2012: Dr Jnanesh Thacker, consultant cardiovascular and thoracic surgeon, Hinduja Hospital, Mumbai, performed the first successful lung transplant in India.

- 2014: Cases of swap donation introduced in amended THOA. Swap donations are to be approved by the authorisation committee of the hospital, district or state where transplantation is to be done. Donations permissible only from near relatives of swap recipients.

- 2018: On 16 June, Indore created a record in central India by facilitating its 32nd green corridor in the past 32 months, for a kidney transplant.

- 2018: On 27 June, NOTTO (National Organ and Tissue Transplant Organisation) provided a green corridor for a heart from Mumbai to Delhi, covering a distance of 1,178 km in just 2:30 hours.

WHAT TAMIL NADU GOT RIGHT!

- Focus on promoting deceased organ donation

- Emphasis on not letting organs go to waste

- First state to make declaring brain death mandatory

- Training transplant coordinators

- Implementation of transplant guidelines

- Centralised waiting list

- Set of guidelines for hospitals that are not retrieval or transplant centres

PRESERVATION OF ORGANS

- Heart: 4 hours after removal from the donor

- Lung: 8-11 hours

- Liver: 12-18 hours

- Pancreas: 8-12 hours

- Intestines: 7-8 hours

- Kidneys: 24-48 hours

USEFUL LINKS

- Donate Organs, Save Lives: donatelifeindia.org

- International Registry in Organ Donation and Transplantation (IRODaT): irodat.org

- Multi Organ Harvesting and Aid Network (MOHAN) Foundation: mohanfoundation.org

- National Organ and Transplant Organisation (NOTTO): notto.gov.in

- Shatayu – A Gift of Life: shatayu org.in

- The Organ Receiving and Giving Awareness Network (ORGAN): organindia.org

- Zublee Foundation: zubleefoundation.com

Photo: iStock Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine August 2018

you may also like to read

-

Hot tea!

If you enjoy sipping on that steaming hot cup of tea, think twice. New research establishes a link between drinking….

-

Weight and watch

If you have stayed away from lifting weights at the gym, thinking it might not be a good idea for….

-

Toothy truth

Research has established a clear association between cognitive function and tooth loss when cognitive function score was categorised into quintiles…..

-

PRODUCT OF THE MONTH

Automatic Blood Pressure Monitor Measure your blood pressure and pulse rate with no fuss Hypertension, or high blood pressure, could….