Etcetera

The individual Aesthetic

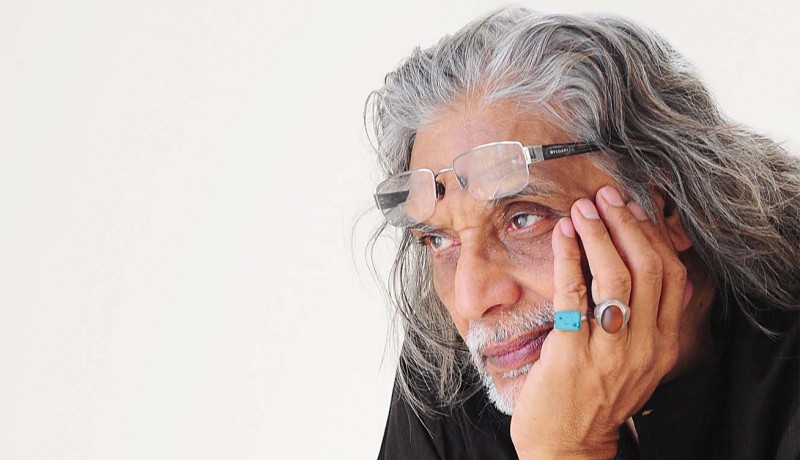

Follow tradition and pay heed to your heart when it comes to your clothes, writes Muzaffar Ali

Each person has a fascination and urge for exploration of their clothing. So do I. The only difference is that I am not just a wearer but an innovator of sorts. And that too has its own journey. I have loved clothes since I was a child. I loved them on my father and on my mother, each with a different eye, with a different passion. Since then I have followed this passion in different ways. It was a romance inspired by the legacy of Awadh’s graceful dressing and working with the rural folk in Kotwara, with the epicentre of the tradition in Lucknow, known for its delicacy and finesse in clothing, couture and craftsmanship.

An age-old saying of Lucknow that still reverberates with me is ‘Khaana khaye mann bhaata, kapra pahne jag bhaata’; it means ‘Eat what you like and wear what others like’. Here, the definitions of mann and jag define the parameters of culture. Jag is a collective sensibility of beauty of a society that evolves from an individual’s aesthetics, which is mann. In the matter of clothes, one always places oneself in a position of making an impression and feeling of ease in different occasions. In cultured societies, people don’t have to shout what they are wearing. People understand the subtle nuances of fabrics and their worth. Today, our society is going through a transition on one hand and stratification on the other. On the other hand, owing to westernisation, we are losing our identity in colourful ethnic ambiences like Rajasthan, Kathiawar in desert landscapes, Kashmir and other hilly regions, Kerala and coastal cultures, Madhya Pradesh, Bengal, and so on.

My own take on clothing comes from what I would like to see people around me wearing. Most of the time, you look at others rather than see yourself. First, the richness of handcrafting is enormously romantic and exquisitely attractive. The idea of any detailed human effort on a body makes me sit up and look. I would start with the fabric itself. There is nothing more beautiful than a handwoven and handspun fabric in India. This is the silent, unseen and unintended aesthetic revolution that India inherited with Independence in 1947. It speaks volumes and solves a million issues of self-reliance and sustainability, particularly in rural India, and also impacts the urban mind.

I would like to share the story of my own cultivation of this form of fabric. My father, who studied in Scotland since childhood wearing the best of English fabrics, suddenly came to India and vowed to only wear handwoven and hand-spun fabric. As an impressionable child, this made an indelible impact on me. From richly adorned occasion wear, or a bespoke serge, to a subtly textured khadi kurta, pyjama and sherwani. It took me time to understand this statement but, in time, I did. Today, I feel this area of fabric development needs attention and offers huge possibilities in design innovation and social emancipation. I can see the blurring of the mann and the jag lines.

Clothes have been close to my passion for filmmaking. In each film I have made, costumes, like music, have been part of my creative expression and organically connected the issues touched in them:

- Gaman, the feeling of helplessness of the people of Kotwara, who migrate to big cities for jobs. This film made me take a full circle and address the issue of what I wear, and would like to see the world wear, through craft.

- Umrao Jaan, which became a benchmark for the cultural finesse that was the fountainhead of graceful couture in India and a seminal point of reference in style.

- Anjuman, set in today’s Lucknow, which takes one into the heart of Chikan craft, reflecting both the beauty and the heartbreak of fading eyesights and nimble fingers.

- Aagaman, another exemplary film in the use of khadi textures.

- Jaanisaar, set in Awadh 20 years after 1857, the first war of Indian Independence, and reflecting the early colonial influence on society, particularly the evolution of the Anglo-Awadhian style that would set the trend for today’s opulent haute couture, especially trendsetting for weddings.

With this eventful exploration I design for myself knowing full well that I am right in what I do. And with this conviction, you see for yourself the saying take a full turnaround: Kapra pehne mann bhaata—wear what your heart says! As a result of this, I scan a wearer threadbare for taste and selection. I can see where they have exercised taste and ingenuity or have got carried away foolishly by the jag bhaata syndrome. I love buying good clothes but only when the apparel has all the intrinsic values that make an ensemble stand out. I am amazed at the unwearable nature of couture as it is entirely out of sync with one’s social milieu. I am equally stunned to see a hundred saris in which not even one has upheld the aesthetics of a tradition or is honest about the innovation of a new idiom. That said, the clothing world is going to grow and grow till the end of time, creating more and more room on the top. What I grew up hearing, ‘Respect what you wear and what you wear will accord you respect’, cannot be more true than now—and will remain true in time to come.

Muzaffar Ali is a filmmaker and painter. Ali and his wife Meera have created a brand, Kotwara, which has imbibed tradition over centuries, blending the best of the East with the best of the West, and reinventing it in today’s globalised context

Photo courtesy: Muzaffar Ali Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine June 2016

WORLDVIEW

WOMAN

MAN: CELEBSPEAK

FASHION POLICE

WOMAN: CELEBSPEAK

MAN

WOMAN: COLUMN

REVIVAL

MAKEUP

HAIR

THE BIG PICTURE

OUR WINNERS

LOOK BOOK

you may also like to read

-

Cracking the longevity code

Small yet impactful choices can be game-changers, writes Srirekha Pillai At 102, there’s no stopping Chandigarh-based Man Kaur, the world’s….

-

Home, not alone

While a regulatory framework is vital for senior-care facilities, the need of the hour is to develop an ecosystem to….

-

Birthday Girl

Published in a special edition to honour Japanese master storyteller Haruki Murakami’s 70th birthday, Birthday Girl (Penguin; Rs 100; 42….

-

A huge treat for music lovers

Published as the revised and updated second edition, Incomparable Sachin Dev Burman (Blue Pencil; Rs. 599; 470 pages) the authoritative….