Etcetera

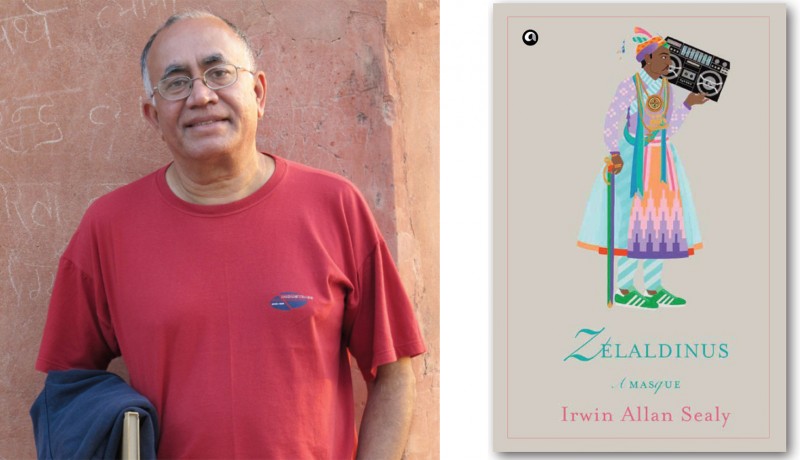

In 1988, Irwin Allan Sealy astounded the literary world with his debut novel The Trotter-Nama: A Chronicle, published by legendary New York-based publishing house KNOPF. The book chronicled seven generations of an Anglo-Indian family in India. A year later, Penguin published British and Indian editions of the book. It went on to win the Commonwealth Writers Prize in 1989 for the best first book by a writer in Europe and South Asia, and the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1991. His latest book, with the title Zelaldinus: A Masque (Aleph Book Company; ₹ 399; 157 pages), is distinctive in many ways. Hardly a few weeks into the market, it has already created a stir. Is it a novella in the traditional sense? Is it prose or verse? Is it history or the figment of a wild imagination? It is difficult to place the book in a specific genre.

Over the past 30 years, Sealy has authored seven books including The Everest Hotel, which was shortlisted for the Booker. The most unique thing about Sealy is that unlike most authors whose books can easily be fitted into a straitjacket genre, each of his works is different in theme and style. In fact, he is least bothered about things like ‘genre’! Sealy’s writing is essentially intuitive and not measured or laboured; he admits that he does not have a routine when it comes to writing. His heart guides his fingers. Little wonder then, that he does not write a book every year—The Small Wild Goose Pagoda was published in 2014 after a gap of 10 years during which the writer was apprenticed to a bricklayer.

The son of a police officer, Sealy has studied in Lucknow, Delhi and Western Michigan University. Cushla, his wife of 40 years, is a New Zealander whom he met while teaching at the University of Sydney, Australia. Their daughter, who works for an environmental agency in New Zealand, is also a freelance writer. The Sealys, who have been living in Dehradun for many years now, spend quite a bit of time in New Zealand. The 66 year-old, who owns neither a mobile nor TV, talks to Raj Kanwar about the art of writing. Excerpts from the interview:

You don’t buy newspapers. How do you keep in touch with the world?

My laptop helps me keep in touch with the world. I can download books and papers, listen to podcasts, stream live video, talk to my daughter in New Zealand, and read any of the hundred newspapers online. In fact, I find it hard to believe that in this day and age we are still cutting down forests for newsprint. On the one hand, we tell our children to plant trees and, on the other, we read newspapers in their presence. Shame on us!

Zelaldinus: A Masque is an unusual story with an offbeat twist. What is the meaning behind the tongue-twisting title?

It’s not so unusual a subject—Akbar the Great—but yes I have given it an offbeat twist. Akbar is the Zelaldinus of the title, and the tongue-twister is simply his name Latinised, because Jalaluddin was a tongue twister for the Jesuit fathers at his court! The emperor had sent for them to join in religious discussions—as you know, he was interested in all faiths and went on to found his own—and they wrote long letters in Latin to Rome in which they called the king Zelaldinus. In the book, which is actually a series of poems, I imagine meeting Akbar and chatting with him about India today. The narrator of the story, Irv, goes to Fatehpur Sikri on a blazing hot day in June and sees the ghost of Akbar who shows him around the dead city. Irv returns in midwinter to find the ghost fretting to leave Sikri. So, together they devise a plot by which the king ends up on the Pak border assisting a pair of star-crossed lovers from either side. The story developed slowly into a masque or a piece of court theatre when I remembered that there was in the Diwan-E-Khas an open-air terrace set up as a pacchisi board where Akbar was said to play a kind of human chess, using for pieces women from his harem of 300.

Is it your yearning to take a road less travelled that prompts you to pick up an altogether disparate theme and different treatment each time you write a new book?

The road less travelled, certainly. Nobody wants the straitjacket, when even house arrest would make you chafe! So you look, instinctively I think, in quite the opposite direction every time you start out; or rather all the time your mind has been sitting fallow you’ve been looking for a new set of constraints, a different kind of jacket if you like, but one that leaves your arms free to signal.

Talking about The Trotter-Nama: A Chronicle, how did you zero in on the theme of Anglo-Indians in India? Isn’t the community now virtually an endangered species?

I happen to be an Anglo-Indian—and yes, we’re not threatening to take over the planet—so when I looked around me at the start of my career as a writer I saw a theme ready and waiting, especially as it had only ever been attempted by outsiders who got it wrong every time. So I was looking to set the record straight. I speak of a career, but it only appears so in retrospect: I didn’t set out to be a Writer. I don’t think we’re worthy of the capital letter.

How has the community helped in the growth of English-medium education in India?

Everybody talks about Macaulay’s minute, where the British Raj set out to create a class of Indian Englishmen here through education in the English language. What they don’t realise is that Macaulay was a late development: Anglo-Indians had been teaching the English language privately in their homes for centuries before that. It was a kind of cottage industry: they were called dame schools, because the teacher was usually the lady of the house, a mature dame, who retailed her mother tongue for a fee. And there was no shortage of takers, even in the beginning, for this English-medium tutoring. My mother ran a dame school when I was a boy in a town too small for a proper school—Fatehpur, where my father was posted with the UP Police. She was a trained teacher who got her BA from Allahabad University and her licentiate from the renowned Isabella Thoburn College in Lucknow. My sister and I had for schoolmates the children of local magistrates and judges and civil surgeons and whatnot. Anglo-Indians have always been teachers; even at church-run schools until recent times, the staff was preponderantly from their ranks.

Why is it that you give each of your books a subtitle? Do these subtitles have any special meaning or is it just an idiosyncratic practice of yours?

It’s partly idiosyncratic, but partly a pointer for the reader, a subtitle always is: it tells you something by way of orientation before you set out, and it’s a useful compass to have in your pocket if you go astray. Of course you need to know what an ‘Almanac’ is, for starters, and if you’re familiar with the genre—the weather guides, the seed-sowing advice, the sunrise and moonset and high tide and low tide charts, the proverbs and recipes along the way—then you gain an appreciation of what I’m trying to do in The Small Wild Goose Pagoda, which has that subtitle. In that book, I set out to write the natural and social history of just this little plot of land, 433 square yards, of Dehra Dun which is my corner of India. I’ve always maintained it is useless making large pronouncements about any country; in fact I distrust any book that has ‘India’ in the title. What presumption! The best you can hope for is to know your own patch intimately. What could I possibly say about Kerala?

What does writing mean to you, and what sort of literary legacy are you planning to leave for the next generation?

The satisfactions of writing are immense and to my mind immeasurable; I’m convinced that the pleasures of the trade—not your royalties—are your earnings. Goals you set book by book, not across a lifetime, and mostly you fall short. The thresholds are reachable, crossable; the ceilings you can’t hope to touch. Chekhov is one ceiling, Calvino is another, Babel a third, and so on. Legacies are always problematic, and each generation must work out its own literary fate. I’d like to think my work illustrates a need to ground your writing in the soil about you, not in models from Europe or America or any of those immensely fertile and attractive but alien fields. But the future is international and who knows where it’ll lead. What’s indisputable, however, is the need to master your own idiom before you set about globalising.

I understand that you don’t have a regular writing routine. What is your writing process like?

My output is pitiful, especially when you consider I have a house to finish building and a garden to manage and bread to bake. Prolonged physical work leaves you drained and unfit for writing, but I’m making notes all the time. I work more deliberately the older I get and yet the best stuff, whether in the world or on the page, happens quickly and easily. It’s the underpinning that’s hard. The raw stage of writing is in any case far more pleasurable than the finished. Writing hours vary widely depending on the circumstances: certain books were night-owl music, others dawn birds. During the day there’s housework and general upkeep. I sleep four hours a night.

Photo: Sharmistha Mohanty Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine August 2017

you may also like to read

-

Cracking the longevity code

Small yet impactful choices can be game-changers, writes Srirekha Pillai At 102, there’s no stopping Chandigarh-based Man Kaur, the world’s….

-

Home, not alone

While a regulatory framework is vital for senior-care facilities, the need of the hour is to develop an ecosystem to….

-

Birthday Girl

Published in a special edition to honour Japanese master storyteller Haruki Murakami’s 70th birthday, Birthday Girl (Penguin; Rs 100; 42….

-

A huge treat for music lovers

Published as the revised and updated second edition, Incomparable Sachin Dev Burman (Blue Pencil; Rs. 599; 470 pages) the authoritative….