Etcetera

The fragile beauty of the Kumaon region in Uttarakhand is but the visible face of a landscape that weaves many narratives. Nestled in the foothills of the Himalaya, it is a deep and rich canvas where nature blends with history, mysticism, spirituality, culture, politics and the pahari (mountain) way of life. Tying together all these skeins is an all-encompassing sacred truth: Nanda Devi, patron goddess of the region. Delhi-based writer, critic, scholar and artist Manju Kak explores these various aspects of Kumaon in her recent book In The Shadow Of The Devi: Kumaon – Of A Land, A People, A Craft (Niyogi; 255 pages; ₹ 1,995).

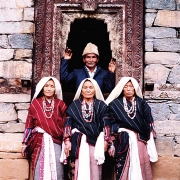

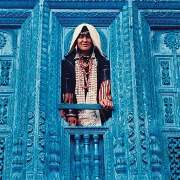

“The book is the result of years of piecing together the story of a land that became the 27th state of India: Uttarakhand. It is the story of a people who have flourished in the shadow of the Nanda Devi range,” says Kak, whose understanding of the region is rooted in the 11 years she spent in St Mary’s Convent (informally called Ramnee), a boarding school in Nainital. Complementing the author’s exploration into the Kumaon people’s woodcraft legacies, the role of the Kumaon women and the region’s environmental faculties is the engaging visual imagery captured primarily by Kumaoni photographer Anup Sah, and contributed to by environmentalist and photographer Vaibhav Kaul, and others. “You can feel the love Anup has for the land,” adds Kak. “Being a trekker and wildlife lover, Vaibhav had been to many of the places that I had visited and researched but could not so eloquently capture.” In an email interview, Kak talks to Suparna-Saraswati Puri about her book and why researching and writing it was such a personal journey for her.

EXCERPTS

You spent your childhood at a school in the Kumaon….

I grew up in the colonial district of Nainital in Kumaon, where the missionaries had brought in education and healthcare. Their efforts at proselytising or educating rested lightly upon the topography beneath, with which they had no real concern. Englishmen who travelled the land made copious notes but they seemed oblivious to what lay beneath. Neither they nor the missionaries really understood the ‘Pahad’ or the ‘Pahari’. ‘Golu’ was a pan-Kumaoni God, who is worshiped in little, whitewashed mounds like gompa and one whom I had never heard of or encountered in the 11 years I spent in Nainital. How could Golu command so much devotion; how could his domed shrines crop up at frequent intervals just about everywhere and have gone unnoticed by them?

As an adult, what did you see in the Kumaon?

Asking questions about the nature of belief in the ‘Pahad’ took me down a road that allowed me to encounter their folk gods, the pari and kechrie, their garh devis in nullah, and the bhoot and paret that were so much a part of their lives, their understanding of the importance of the devilish functions of the supernatural along with the innate good present in nature. Indeed, colonial Kumaon was abandoned in favour of mythology and ritual—the worship of Dhunia and Kshetrapal. Some talented songster would emerge to regale us with a ballad or two, or we would be taken to a medium who would recount her own journey into the practices of tantrik magic or show her prowess in reading rice grains or foretelling the future. It was interesting that these beliefs were so much closer to village life than the high pantheon of Hindu gods for which these hills are known. For the ordinary Kumaoni villager, it was Golu devta all the way.

You have dedicated a large portion of your book to the exquisite woodwork of the Kumaon craftsmen. What is their status now?

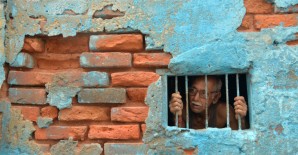

The craft of woodcarving can be regarded as one of the most representative, aesthetic traditions of this land. Found on the beautiful doorways of village homes, I use woodcarving as a metaphor for understanding the people, caste structures, and environmental policies because the wood used—the tun—became a very rare species owing to the environmentally insensitive policies of colonial rule. The state of these shilpkaar [craftsman] villagers has worsened. In the hills, segregation as a result of the caste system became painfully clear. In fact, even when developmental work began, water pipes that were sanctioned would end up hundreds of metres from where these villages were. The poverty, hardship, lack of healthcare facilities and extreme despondency of never seeing change have seeped into the collective village consciousness.

The women of the Kumaon have played a significant role in the region’s recent history. What is their story?

Interestingly, it was my dhoban who began this book’s story. One early April morning, I asked her where she was coming from. She said, ‘Last night, I went to meet the Devi,’ and she pointed to the Nanda Devi range as if it was a person. I am not sure what answer the Devi gave Sheela but it made me curious—her implicit belief that the Devi and she were friends, and if she trusted this Mother Goddess enough, a solution would be found. Uttarakhand owes its existence to the sturdy courageous women of these hills, who from the times before Chipko raised their voices for a saner, kinder, more environment-friendly world. Pahari women are known to be free-willed and tough, and they could put our urban feminists to shame. It is no surprise that the prevailing reverence for Shakti, or Devi, is all-pervading.

How has the Kumaon evolved since the formation of Uttarakhand?

There is a huge sense of regret because, somehow, the vision of the people who actually worked for statehood got left behind. Today, the state exemplifies all the ills of Uttar Pradesh, from which it was carved. The same illnesses plague the state, from alcoholism to plunder by the timber mafia, illegal mining and land grabbing. Increasingly, the crimes of the plains are on the rise and the ideals upon which the struggle for statehood gained ground are disappearing.

Photographs by Anup Sah; courtesy: Niyogi Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine August 2017

you may also like to read

-

Cracking the longevity code

Small yet impactful choices can be game-changers, writes Srirekha Pillai At 102, there’s no stopping Chandigarh-based Man Kaur, the world’s….

-

Home, not alone

While a regulatory framework is vital for senior-care facilities, the need of the hour is to develop an ecosystem to….

-

Birthday Girl

Published in a special edition to honour Japanese master storyteller Haruki Murakami’s 70th birthday, Birthday Girl (Penguin; Rs 100; 42….

-

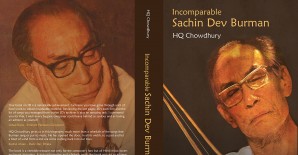

A huge treat for music lovers

Published as the revised and updated second edition, Incomparable Sachin Dev Burman (Blue Pencil; Rs. 599; 470 pages) the authoritative….