People

The first female exponent of this classical musical tradition, Dr Madhu Bhatt Tailang is striving to ensure it does not remain a male preserve, writes Prakash Bhandari

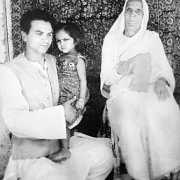

In the Bramhapuri locality of Jaipur’s walled city, one house attracts more attention than most. Called ‘Dhruvpad Dham’, it is adorned with metal wire sculptures of the pakhawaj, veena, mridang and tanpura on its gate. This is no random choice of musical instruments; these are the instruments that accompany the oldest existing form of classical Indian music, called Dhruvpad. Given its décor, this could only be the home of Dr Madhu Bhatt Tailang, the first female singer of this centuries-old form of music. She lives here with her father, the much-revered Dhruvpad exponent, Pandit Laxman Bhatt Tailang, 89.

“The origin of Dhruvpad is linked to the recitation of the Sama Veda [the sacred Sanskrit text] and is a meditative yoga or prayer in vocal form,” explains Dr Tailang. “Its sound and resonance keep the body, mind and soul in a peaceful and healthy consonance. It is much more than mere music.” The Tailangs belong to the Vallabhacharya Vaishnava sect and are traditionally singers in the temples of Lord Krishna. “Our family moved from today’s Telangana to the north of India a very long time ago,” reveals Dr Tailang. She adds that Jaipur has been the home of Dhruvpad singing ever since their ancestors were invited to the darbar of Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II in the 19th century.

Dr Tailang is the only child of Pandit Laxman to follow in his footsteps. “Not all my daughters learnt Dhruvpad. Madhu had a penchant and passion for it, and it was she who wanted to become a Dhruvpad singer in true family spirit. She has a voice that matches the resounding rhythm of the pakhawaj,” says Pandit Laxman, who taught his daughter music orally, as is tradition, from the age of five.

With two master’s degrees and a PhD in ‘Dhruvpad Musical Dynasties’, Dr Tailang has mentored 22 students who have obtained their doctorates in music. She currently heads the Department of Music and is dean of the faculty of fine arts at the University of Rajasthan. Indeed, both father and daughter are passionate about teaching their craft and set up the International Dhruvpad Dham Trust in 2001 to teach students for free. “The future of Dhruvpad singing will no more remain a male domain and a number of my students will take centre-stage,” insists Dr Tailang in her powerful voice that is so beautifully suited to this classical musical art. They also run the Ras Manjari Sangeetopasna Kendra, where students can learn other forms of Indian classical music.

Father and daughter are so totally in sync that even the Gods seem to stop and listen to them sing. “When we were performing at the Dhruvpad Samaroh in Vrindavan on a sunny afternoon many years ago, Madhu and I started singing raga Miyan Malhar. Suddenly, it started drizzling. Soon, the skies opened up and it started pouring as we sang, invoking the rains. This was the effect of our jugalbandi [duet],” recalls Pandit Laxman.

IN HER OWN WORDS

I started learning Dhruvpad when I was five years old, whereas my sisters and brother opted to learn to other forms of classical vocal music or to play the sitar. Riyaz would begin at 4 am for my eldest sister and, an hour later, the rest of us would be woken up to join her. We all took turns at singing or playing, while the others paid attention. After school, we’d return and it would be time for riyaz again. We spent eight hours a day in riyaz, a habit I maintain to this day. I don’t think I have slept for more than five hours a day my entire life.

When I was 13, I took part in my first singing contest. It was conducted by the Central Government’s Ministry of Art and Culture. My father prepared me with a Dhruvpad composition. I won the competition and received my first scholarship. The guests at the competition were surprised to see a girl singing Dhruvpad. At that time, it didn’t strike me as out of the ordinary. That is when I decided I wanted to be a Dhruvpad singer.

My father taught all of us—six girls and one boy—but never pushed any of us to take up music professionally. He was happy with my decision as he believed my deep voice suited Dhruvpad more than any other classical form. It was up to me to carry forward my father’s legacy. For the many scholarships that came my way, I was often asked who I would prefer as my guru. For me, the answer was always the same.

My father took care to balance his roles as parent and teacher. When he would make us accompany him on the tanpura at concerts, I distinctly remember the delicious rabadi and mawa he would feed us on stage. I also remember all these people coming to pay their respects to him. That’s when we’d get a glimpse at how respected our father was.

My mother, who belonged to the same community of devotional singers, was married to my father because of his musical tradition. She would rise before us and get us ready for practice. The chores were divided equally among us children. And when father was away, my mother would take his place as guru and teach us. She was attentive to who was weak in a particular swara or raga, and help them individually.

When I was around 20 years old, my father took me to Ambitjugai in Maharashtra, where the Sangeet Natak Akademi had organised a Dhruvpad mela. I was to accompany him on the tanpura. There, I was noticed by Dr Premlata Sharma, the first female musicologist, who was one of the organisers. She invited me to open the seminar the next morning, making it my first public concert. After that, my career took off.

My father is very progressive with his music even though he was brought up in a traditional school of learning. Before my father, all the Dhruvpad gharana involved singing devotional songs. He said we had been singing those tunes for centuries and even the audience is bored of them. Devotion is not limited to Krishna and Radha. It can also be towards one’s country, he would say. So he started setting Sare jahan se achha, Vande mataram and even the Raam dhun of Gandhi to Dhruvpad. He has over 500 such compositions, the most attributed to any Dhruvpad composer.

Dhruvpad has long been an isolated vocal tradition, only truly appreciated within the musical community but, for my father, this was not good enough. So he reinvented the form by introducing a lighter, fifth element to the existing four, known as the Chaturang: bandish, the summary of a raga; sargam, singing notes instead of words; tarana, nonsense syllables used at a brisk pace; and hawaj bol, making the sounds of the pakhawaj—within which each composition is performed. My father included a folk or semi-classical element for a lighter singing form, thereby making the music more accessible to classical music fans. It is called Pachrang.

My father has opened the art to the many students who are now spread throughout the world. He used to say that this art has been passed down to us across generations, and now is the time for us to let it out. And he finds interesting ways to teach each of his pupils—we call it learning through play. For example, one of the swara is ma pa ni pa re, which in Rajasthani translates to the child telling her mother that it is raining… Ma, paani pare!

People compare me to my father and I feel a great sense of pride that they see him in me. But when your father is your guru, you have to prove your worth as his name is attached to it. Before beginning any concert, I pray to the Gods for strength to preserve my family name.

My father is a man of many talents, including being a handyman. If any machine in the house is broken, like a watch or the television, he repairs it himself. And when we were children, he would stitch our clothes and even cook great food for us sometimes.

Like my father, music is not my only gift. I like to dance and have spent over 12 years of my young life learning Bharatanatyam, Kathak and Manipuri at Banasthali. My father thought it would help me find more rhythm in my music. I don’t have much time for it now but I still dance sometimes.

I was married once. My parents looked for someone with an open mind to let me practise my art. We learnt of this boy who was a lawyer and was also interested in theatre. But you don’t always get the full picture from the outside. We divorced in 1997, without any children. To fill that space in my life, I started teaching children free of charge. Rather than having one or two kids, I have thousands, of different ages. I live with my father now. He has given me his land, which I have made into the Dhruvpad Dham institute. This is now home.

Photos: Surendra Jain Paras Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine July 2017

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….