People

One of the foremost authorities on tigers in the world, Ullas Karanth has given the art of wildlife conservation in India a scientific makeover, writes Srirekha Pillai

Tiger, tiger, burning bright

In the forests of the night,

What immortal hand or eye

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

—William Blake

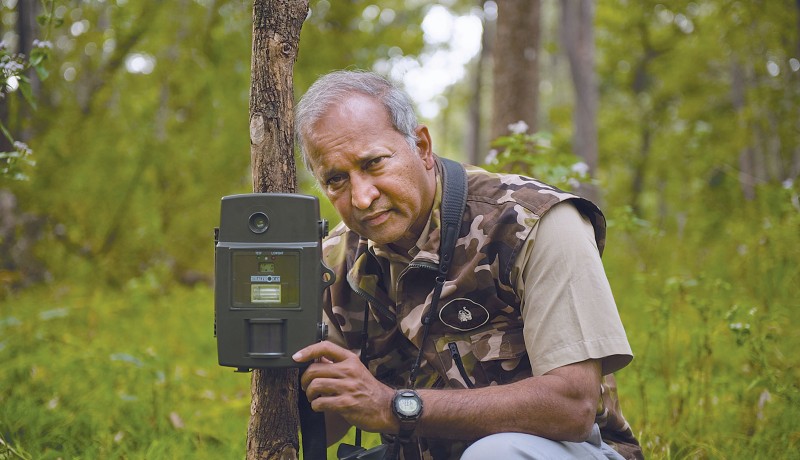

Rarely has an animal exercised such pull and power on the collective human psyche as this magnificent beast. Paeans have been penned, shrines built and folklore spun around it. A mascot for endangered animals, the tiger has been able to reclaim lost ground in India, thanks in great part to the path-breaking scientific approach of Bengaluru-based wildlife conservationist K Ullas Karanth. His invention of using camera traps to estimate tiger populations has been incorporated by the National Tiger Conservation Authority in its tiger census methodology. In fact, the Indian programme of the New York-headquartered Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), initiated by Karanth in 1988, has played a significant role in tiger recovery efforts in the country. Today, over 70 per cent of the world’s wild tigers are found in India, although the country is home to less than 25 per cent of its habitat.

Director of the India programme of the WCS and the founder of Centre for Wildlife Studies—a non-profit trust based in Bengaluru for conservation of wildlife and wild lands—Karanth’s love affair with the big cat goes back to a childhood spent in Puttur in Dakshina Kannada district of Karnataka. Born to Jnanpith-winning Kannada writer Kota Shivaram Karanth, who was also known for his social activism and environmental zeal, it was but natural that Karanth veered towards nature and animals. “My father had a mini zoo at home,” he says. “I remember seeing peafowl and hare. Earlier, we had sambar, blackbucks and chital. People from all over Puttur came to see them.”

Hulivesha or the tiger dance, the centrepiece of Dasara celebrations in Dakshina Kannada, also fascinated a young Karanth who would follow the dancers painted in patterns of ochre, white and black moving to the crescendo of drumbeats through the dusty roads of the village. As a five year-old, when he saw a tiger for the very first time at a circus, Karanth was hooked. “Influences come from different directions,” he notes. “We have a strong animistic element in the culture of Malenad. There are shrines to the tiger, the gaur and other animals.” Karanth also grew up on stacks of nature books and Jim Corbett’s tales of man-eaters found in his father’s library.

Meanwhile, the first edition of ornithologist Salim Ali’s Book of Indian Birds, gifted by one of his aunts, initiated him into bird-watching. Later, while training to be an engineer at the National Institute of Technology at Surathkal, Karanth read the founding father of wildlife conservation George Schaller, credited with the first scientific study of tigers. “When I read him, it all came together. I realised conservation was science, just like engineering. At that point, I decided to work towards being a wildlife biologist.” To understand the broader issues and challenges of conservation, Karanth started accompanying his cousin, senior forester Shyam Sunder, to the jungle. During these trips, he also befriended K M Chinnappa, a forest ranger who taught him how to track animals and read signs and sounds of the jungle, such as a crackling twig or the flight of birds.

After working as an engineer for almost five years, which left him feeling “stifled”, Karanth finally bought a farm north of Nagarhole National Park, and started farming for a living. He used the opportunity to renew ties with nature, visit the park and engage in conservation advocacy. He also started writing and publishing on natural history and undertook wildlife surveys. In 1986, at the age of 36, Karanth earned admission to the University of Florida’s Wildlife Ecology and Conservation Programme. When he graduated, Schaller selected him to build the WCS programme in India.

Buoyed by the exposure to the latest research methodologies in the US, when Karanth returned to India, he tried to instil a scientific spirit in the way wildlife was monitored in the country. “We were censusing tigers by identifying paw prints and tracing tracks. Though Corbett and other skilled naturalists had occasionally recognised some tracks, the census had no basis in science.” Karanth suggested putting cameras triggered by wildlife sensors in the forests to take photos and identify tigers through stripe patterns. “Stripes differ from tiger to tiger and from side to side. To identify an individual tiger, you need images of both sides,” he elaborates. “We have built some sophisticated pattern-matching software to do the first screening, so that eyeballing can be limited to the final few.”

Karanth is known for pioneering the use of camera traps in studying prey-predator relations. The capture-recapture sampling—taking a sample of animals, marking and releasing them; taking a second sample after a few days with both marked and unmarked animals; and using that ratio to estimate the total population—introduced by Karanth in India was far more reliable than the ‘pugmark’ census which demanded every tiger be identified and counted. Besides the tiger, this method has since then been used to estimate populations of leopards, jaguars, snow leopards and cheetahs worldwide. Karanth has also championed the use of occupancy sampling by simply counting tiger signs—developed by him and American statistical ecologist Jim Nichols—to estimate spatial distribution of tigers across larger regions. His scientific approach has helped arrive at a far more accurate picture of the tiger population in India.

Chief wildlife warden of Rajasthan G V Reddy credits Karanth with pioneering the use of scientific tools in wildlife conservation in India. “Karanth is a passionate conservationist who has fought and convinced the system to change its approach towards wildlife monitoring,” he says. “The tiger census practised today is based

on the camera-trap methodology he introduced. Our approach earlier was intuition-based; he has brought in the scientific edge.” Admiring Karanth for putting into practice “whatever scientific knowledge he has gathered”, Reddy also applauds him for “building a core of science-based wildlifers to carry on his legacy”. For his efforts, Karanth has received accolades aplenty, including the Padma Shri (2012); the Salim Ali National Award for Conservation from the Bombay Natural History Society (2008); J Paul Getty Award for Conservation Leadership from the World Wildlife Fund (2007); the Sanctuary Asia Lifetime Achievement Award (2007); and the Sierra Club International Earthcare Award (2006).

However, Karanth’s struggle to make science acceptable in the field of wildlife conservation hasn’t come easy. There have been repeated attempts to stall his research. Ruing the lack of a professional wildlife culture in the country, Karanth observes, “The need for hard science in conservation is not appreciated in our country to this day.” He recalls how his work was targeted for the first time in 1990, when the death of some tigers was wrongly ascribed to radio collars on them. He got the stay vacated in the Supreme Court. “I have never compromised on what I believe in,” he says.

Concurring that being the glamorous leader of the pack, the tiger has a huge advantage over other endangered animals, Karanth observes that it has its flipside too. “It’s the same cultural resonance of the tiger that drives the oriental medicine market, with massive smuggling rings thriving on tiger parts and bones.” Besides the tiger, Karanth’s team also strives to protect endangered species such as the Asiatic elephant, lion-tailed macaque, leopard, dhole, and the great pied hornbill, among others.

Identifying illegal hunting as the greatest threat to wildlife in India, the 68 year-old says, “If we can stop that, we will have four times the number of wildlife we have now.” He is also concerned about the targeted hunting of high-value species such as rhinoceros, tigers and elephants in protected areas. That said, Karanth says things have come a long way since his childhood when there were no conservation laws. “I see Indian wildlife as a half-full cup now. As a 10 year-old boy, I used to worry tigers would go extinct in my lifetime as animals were being hunted down and forests wiped clear for agriculture.” He suggests reconciling conservation with development by spatially separating lands for conservation, urbanisation and agriculture.

“He is a visionary with few equals in this field,” says wildlife and conservation filmmaker Shekar Dattatri, who has worked with Karanth for over 20 years. “Karanth has the ability to see both the big picture as well as the intricate details of complex conservation issues. He is also one of the few wildlife scientists I know who is also an active conservation practitioner.”

Today, Karanth is also assisted in his work by daughter Krithi, who is a conservation scientist with a focus on assessing patterns of species distributions and extinctions, impacts of wildlife tourism, consequences of voluntary resettlement, land use change and understanding human-wildlife interactions. The dad-daughter duo has an easy professional relationship, having even published papers together. His regret, however, is that he was hardly there for her when she was growing up. His wife Prathibha, a speech pathologist who has developed a system for dealing with autistic children, had to virtually bring her up singlehandedly as he was “a weekend husband, out in the wild mostly”.

An avid reader, comfortable with anything from fiction to economics and philosophy, Karanth also loves to spend time with his grandchildren, aged 10 and two. A little known fact, though, is that he paints. “I’m a reasonably good painter. For lack of time though, I haven’t been able to pick up a paintbrush for years now,” he says, admitting that he loves to sketch wildlife. As for any threat to his life in the wild, Karanth adds in a lighter vein, “I’ve darted tigers, caught and tranquilised them. I cannot say I’ve been in a risky situation. I think I run a greater risk when I drive every time from Bangalore to Nagarahole on the highway.”

BOOKING IT

- The Way of the Tiger (2001)

- Tigers (2001)

- Monitoring Tigers and Their Prey (2002)

- A View From the Machan (2006)

- Camera Traps in Animal Ecology (2010)

- The Science of Saving Tigers (2011)

- Science and Conservation of Wildlife Populations (2017)

HIGHLIGHTS

- The WCS-India programme is the longest running scientific study of tigers covering the largest tiger population in the wild, globally.

- Karanth and his collaborators have pioneered the development of new techniques such as photographic capture-recapture sampling, tiger and prey spatial occupancy modelling, line-transect estimation of prey numbers, faecal DNA-based individual identification—all of which are now applied globally.

THE WILDLIFE FACTSHEET

Endemic species

- Almost 33 per cent of plant species are endemic to India, not to be found anywhere else in the world

- Among the 44 species of mammals endemic to India are the Nilgiri tahr, wild ass and the lion-tailed macaque

- The 55 species of birds endemic to India are found mostly in the Western Ghats, eastern India along the mountain chains and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands

- There are around 187 endemic reptiles and 110 endemic amphibian species in India.

Tigers

- According to the World Wildlife Fund and the Global Tiger Forum, the number of wild tigers in 2016 has gone up to 3,890 from 3,200 in 2010

- India is home to 70 per cent of tigers in the world

- The oldest Bengal tiger fossil was found in Sri Lanka, and it has been dated back 16,500 years

- A full-grown male Bengal tiger can weigh up to 420 pounds.

Photographs courtesy: Ullas Karanth Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine June 2017

AGRICULTURE

FORESTS

WATER

WASTE MANAGEMENT

ENERGY

SUSTAINABILITY

EXCLUSIVE COLUMN

EXCLUSIVE COLUMN

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….