People

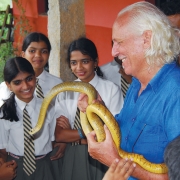

Chennai-based herpetologist Romulus Whitaker has a charm and rare enthusiasm towards creepy-crawlies, and has saved countless lives through his decades-long work, writes Jayanthi Somasundaram

Romulus Whitaker was hard to miss on the streets of Madras in the 1970s. The handsome young man with an American twang and natural swagger would cruise around the city on his motorcycle, a 3-ft snake tangled in his flowing hair.

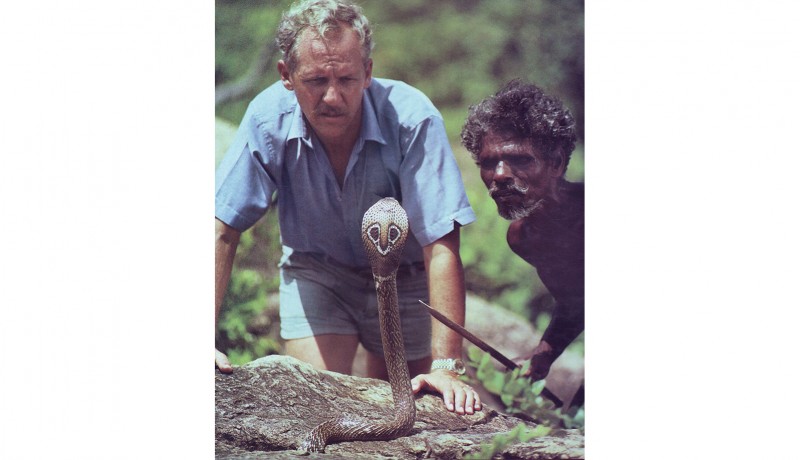

Whitaker was a poster boy all right, just not the typical kind. The arresting image drew international attention to his work with snakes in a country where these reptiles are usually regarded as a symbol of evil. “My favourite image is that of a cobra shielding the Buddha from the sun or being used as a belt by Ganesha or a necklace by Shiva,” says the 75 year-old herpetologist, who was conferred the Padma Shri for his work earlier this year.

Indeed, no single individual has contributed as much to the conservation of snakes and crocodiles in India as Whitaker, who along with like-minded colleagues has set up six pioneering institutions that are changing the way Indians perceive these reptiles. “The best thing about my work is that it sends waves of interest out to younger, more energetic people to keep this work rolling,” says the Chennai-based conservationist, who is famously known for setting up India’s first snake park in the city, then called Madras, in 1972.

Whitaker caught his first snake when he was just four. It was at their family country estate in New York state that he brought home a non-venomous American garter snake. “My mother said, ‘How beautiful!’, and soon she bought me The Boy’s Book of Snakes by Percy A Morris,” he smiles. This was his first book on snakes. It triggered an obsession and soon he started a collection of milk snakes, garters, ribbons and ring-necked snakes at home.

When Whitaker turned seven, his mother married into a well-known Indian family and they moved to Bombay, now Mumbai, in 1951. For the next 10 years, Romulus went to boarding school in Kodaikanal, Tamil Nadu, where he spent his weekends scouting for snakes and learning jungle lore from local hunters in the forests.

After finishing high school in 1960, Whitaker returned to the US for further studies. Following a failed attempt at college and a stint as a travelling salesman and merchant seaman, he worked at the Miami Serpentarium run by legendary snake man Bill Haast, a man he calls his guru, from whom he learned the techniques of safely and humanely extracting venom.

Returning to Madras, Romulus started out by producing and selling snake venom. “I was sourcing snakes, particularly kraits, from all over India and came to know the Irula snake catchers in South India,” he shares. The Irula tribe of Tamil Nadu are aboriginals whose traditional occupation is catching rats and snakes. “When I first met them, all I wanted was to work with them, learn from them, and involve them in developing more of my ideas.”

Eventually he rented a plot of land with an old house, where he put up snake enclosures, a signboard, and got some newspaper publicity. The people of the ‘Land of Snakes’ needed to see and learn about these much-maligned yet fascinating creatures, he reasoned.

The experiment worked. It was also the beginning of Madras Snake Park (now the Chennai Snake Park). “The Tamil Nadu Forest Department gave me a 25-year lease on a plot of lovely scrub jungle in Guindy Deer Park, right in the heart of the city. The new snake park was an overnight success and soon we were getting a million visitors a year.” It attracted generous media coverage and among the high-profile visitors was then prime minister Indira Gandhi. “Mrs Gandhi went away with a new appreciation for snakes, lizards, crocodiles and turtles, which she later acted upon,” says the herpetologist.

From snakes to crocodiles is but a small step and Whitaker soon found himself on a new mission. “My former wife Zai and I realised the snake park was not big enough to breed crocs, which had become endangered in India. So we had to raise money to buy land to set up the Madras Crocodile Bank Trust. We had a total of ₹ 14,000, which we had got as wedding gifts and bought the first 3 acre of what is now the famous croc bank on East Coast Road in Chennai.”

After setting up the crocodile bank, Whitaker went back to university and earned a BSc degree in wildlife management from Pacific Western University in the US. “The only reason I wanted the degree was so that I could apply for a PhD. I thought people would see me as a ‘serious’ herpetologist, not just a ‘pop’ one.” He never did pursue the PhD though as he was having far too much fun chasing snakes in jungles around India and learning on the field.

Whitaker has written over 200 scientific papers on reptiles, in addition to founding India’s first herpetological journal, Hamadryad – Journal of Tropical Asian Herpetology, now in its 37th year of publication. He also has eight books to his credit.

His work on king cobras and snake venom research has been featured in books, magazines, and documentaries, including the Emmy-winning King Cobra produced and directed by Whitaker himself. His fascination for the king cobra, the world’s largest venomous snake, resulted in a collaborative study with Matt Goode, an ophiologist (a herpetologist who specialises in snakes) from the University of Arizona in the US. The study combined research, public education and a plan for the snake’s conservation. “Hundreds of adult king cobras are rescued from people’s homes and gardens every year and many king cobra nests are found and monitored,” he says. “The work goes on and the king cobra has now become the most studied snake of the more than 300 species of snakes found in India.”

Some of Whitaker’s fondest memories are of his snake-hunting adventures with the Irulas. In 1975, hundreds of Irula families were rendered jobless when the snakeskin industry was dealt a death blow. While this was a landmark conservation measure for snakes, for the Irulas, it spelt doom. Whitaker shared his venom extraction knowledge and techniques with the Irulas and set up the Irula Snake Catchers Cooperative Society in 1978.

The Irula Cooperative is the only organisation allowed to make legal use of snakes in India. (They have licences for 8,000 snakes each year for their venom; after extraction, they release them.) It now supplies 80 per cent of the venom needed to make the over 2 million vials of anti-venom used to treat snakebite in India each year. Whitaker has also taken the Irulas to Florida to trap pythons that are wreaking havoc on the endemic mammals and birds in the Everglades National Park.

For Whitaker, embarking on a sub-career in filmmaking in 1985 was purely to reach out to more people. His first film was a collaborative effort with his school friends in 1985. “It was called Snake Bite and was the story of how two people were bitten by snakes. While the first was treated by a village quack, the latter got a shot of anti-venom at the hospital. Anti-venom wins!” he cheers. The film went onto win a gold medal from the British Medical Association.

Later, he produced and directed a full-length feature film, Mudalai (Crocodile) with his former wife Zai, for the Children’s Film Society of India. In 1989, the film won many awards including the Silver Elephant at the 6th International Children’s Film Festival, and Best Feature Film at the International Centre for Film for Children and Young People. Made in Tamil, Hindi and English, the film was also screened as part of a Christmas Eve telecast in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1991.

“This encouraged me to meet the National Geographic people and that’s how I met my wife Janaki Lenin, a film editor. We put together the idea of King Cobra,” he reflects. The 53-minute film, shot in the rainforests of Kerala and Karnataka, won an Emmy Award for Outstanding News and Documentary Programme in 1998. “One of the best things about that project was that we were able to buy a new jeep, which we used to drive around the Western Ghats. We had so much fun that I even thought of telling Nat Geo that I would just do the recee trips,” he jokes.

For someone who can’t stay away from the wilderness, Whitaker now spends a lot of time in front of a computer, writing proposals on behalf of Madras Crocodile Bank Trust, where his son Nikhil is curator. This project researches the venom of snakes from different Indian regions in order to test the efficacy of anti-snake venom. “As the India project manager for the Global Snakebite Initiative, an international NGO, I’m helping to collect venom samples to improve Indian anti-venoms, promoting a nationwide snake conservation and snakebite mitigation outreach programme by producing short videos and involving schools and rural communities,” he tells us. “I’m doing this for the people, as much as I’m doing it for the snakes.”

Like most other wildlife conservationists, Whitaker cannot always quantify his work. But there are times when figures can speak for his success. When he co-authored Snakes of India, the Field Guide in 2004, there were 276 species of snakes that had been documented in the country. As of July 2018, he notes, a total of 302 species have been identified in India, including several wolf snakes, vine snakes, cat snakes and tree snakes.

Whitaker wants people to look at snakes as innocent things of beauty, not vengeful creatures. He believes most children would be fascinated with these reptiles if their parents had not instilled a sense of fear in them.

“Both our boys Nikhil and Samir were fearless about snakes and other creepy crawlies. As parents, we had to actually caution them and teach them what they could and couldn’t touch. Once, Samir came up to us carrying two venomous saw-scaled vipers, exclaiming, ‘See Dada, cat snakes [which are harmless lookalikes of vipers]!’ I calmly told him to put the snakes down, very carefully, and then gave him the requisite shaking and shouting so he’d remember to be more careful,” Whitaker laughs. He still savours the memory of his 8-ft pet python slithering out of his parents’ apartment on Marine Drive, Mumbai, sending his neighbours running for cover! “Later, I found it hiding under a trunk in our own store room,” he grins.

Whitaker points out that snakes are under considerable pressure from habitat loss, especially those that live in the dwindling forests of the Western Ghats. “And in the Eastern Ghats, king cobras are being killed on sight even though there is no record of a king cobra bite in that region,” he rues, admitting that at 75, age has slowed him somewhat. But given the amount of work that is yet to be done, he says he is inspired to act even faster.

Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine November 2018

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….