People

Bengaluru’s Sukanya Ramgopal continues to wage her battle to raise the status of the ghatam and bring recognition to women exponents of this percussion instrument, writes Chitra Ramaswamy

A concert of bells rings out as she deftly moves her fingers across the six ghatams carefully arranged in front of her. As hand meets clay, the tones she produces synchronise into Raga Valaji. The effect is electric.

Vidushi Sukanya Ramgopal’s prodigious talent was not enough to bring her the prestige she deserves as the world’s first female ghatam player. Yet, in a man’s world, she holds her own with poise, accompanying leading and veteran musicians on the ghatams in India and across the world.

Smarting from the duality in this realm of Carnatic music, the 60 year-old maestro has consistently broken new ground as she holds her audience spellbound. From her early years, she has collaborated with international artists of renown; she performed at Germany’s annual Tamburi Mundi or Frame Drum Festival in 2013; she regularly conducts workshops and lecturedemos at music venues across continents; and she revels in a special memory: the appreciation for her fusion piece with Flamenco dancer Bettina Castano.

Ramgopal lives in Bengaluru but she grew up in Triplicane in Chennai, in a family of musicians and Tamil scholars. She is the great-granddaughter of well-known scholar Mahamahopadhyaya Dr U V Swaminatha Iyer, fondly known as ‘Tamil Thatha’, and the grand-niece of music maestro Ghanam Krishna Iyer.

The youngest of five siblings, she began training in vocal music at the age of five. Within a couple of years, the young girl began learning the violin. However, it was the sounds of percussion instruments that moved her. “There was no specific trigger, I just enjoyed percussion very much,” she recalls. “I would get my sister to sing and try to accompany her by tapping on whatever surface was available at hand—a wooden table, a chair… just about any surface.”

The opportunity to train in the mridangam and, later, the ghatam presented itself when she began learning the violin under Shri Gurumurthy, brother of ghatam virtuoso Shri Vikku Vinayakram. The training took place a few buildings away from her residence, at the Shri Jaya Ganesh Talavadya Vidyalaya, a music school established by mridangam maestro Harihara Sarma, father of Gurumurthy and Vinayakram. The young girl would look wistfully at the mridangam class being held opposite the violin class. The urge to learn the instrument was so strong that she impulsively enrolled herself to be trained under Shri Sarma. Her guru delighted in teaching a student with so much commitment and passion and within three years, at the age of 15, she began to accompany artists during concerts.

But her true calling was the ghatam. Mesmerised by Vinayakram’s playing, she approached him to teach her. He tried to dissuade her from learning an instrument that was too ‘manly’ for ladies to play. Ramgopal laughs as she recalls, “When I persisted, he tried to put me off by saying that it was a difficult and rough instrument for women to learn, that it would make my hands sore and bleed.” She was not deterred, however. “I always fancied challenges from childhood; the more I was told something was not possible to do, the greater my urge to do it. Even in matters as simple as taking the name of my school, when asked, I would rattle it in full: ‘N K Tirumalachariar National Girls High School’, whereas all the other students would simply say ‘National School’! I felt I had to be different from the others, do things others felt were difficult or impossible.”

Her firm stand clinched the matter. She had the support of Vinayakram’s father and her mridangam guru. In fact, he undertook to train the 12 year-old himself, saying it would be a matter of pride for his school that a girl was learning and playing the ghatam. He told Vinayakram he would make her proficient in the ghatam and prepare her for concert-level playing within the one-year period when Vinayakram was visiting Berkeley on a teaching assignment.

Thus began her tryst with the ghatam. Whatever her guru Sarma would play on the mridangam, she would translate on the clay instrument. “His training was so perfect and rigorous that within six months, I had completed the lessons and even begun to perform concerts within the year,” remembers Ramgopal. And as Sarma predicted, she began training with Vinayakram promptly a year later.

Learning to play the ghatam was actually the easier part of her musical journey. The real struggle began when she stepped into the world of kutchery or concerts with its rigid hierarchy and prejudices. She faced double marginalisation. First, because the ghatam is treated as upapakkavadhyam or secondary to the mridangam as a percussion instrument; second, as a woman artist. The change in Ramgopal’s body language is palpable as she says vehemently, “I would say the word ‘accompaniment’ itself is wrong—rather, it is teamwork that makes for a concert’s success or otherwise. As for the gender bias, I feel it is no better today than in earlier times, when I began learning the instrument. Renowned musicians would often question Vikku sir on why he was teaching me the ghatam. They would argue that as a lady, I should confine myself to the mridangam! Even today, co-artists heartily applaud male ghatam artistes when they receive a standing ovation, but are not ready to accept it when I receive such applause!”

In her 40 years of experience as a ghatam exponent, Ramgopal has trained over 25 students; only one of them was a girl. Still, the iconoclast is in it for the long haul. And her battle isn’t just against the gender bias—she also wants to get the instrument the respect it deserves.

Her struggle began in the early 1970s, when she addressed a strong letter to All India Radio, Delhi, questioning the step-motherly treatment meted out to players of the ghatam, kanjira and morsing, vis-à-vis mridangam players. Competitions to select and grade artistes did not have separate categories for each percussion instrument and the mridangam invariably ruled the roost. Ramgopal sought separate categories for each of these instruments, and for them to be acknowledged as part of mainstream concerts. Her request bore fruit in subsequent years.

In 1992, Ramgopal conceptualised Ghata Tharang, a musical ensemble with six ghatams of different pitches, occupying centre-stage for the first time in the history of the instrument. The very next year, her Sthree Thaal Tharang, another innovative venture that involved an all-women’s instrumental ensemble, created waves in musical circles in India and overseas. The ensemble performs extensively at festivals and universities across continents.

Despite her several innovations in the field, Ramgopal continued to face animosity from male musicians. In 2000, she encountered one of her most bitter moments when she was to accompany flautist N Ramani during his concert in Bengaluru. When she reached the venue, she was told that the accompanying mridangam artist had refused to share the stage with a female ghatam artiste. “The organisers profusely apologised, hailed a taxi and sent me back. Even upon the deaths of my parents I had not wept as much as I did on that day. The sorrow I felt was indescribable! It was then that I decided I must do something out of the box, something nobody had ventured to do before, to prove women were second to none in any field. I was determined to showcase my talents in a different way. It became almost an obsession.”

In 2014, Ramgopal established the Vikku Vinayakram School for Ghatam in Bengaluru with the sole aim to take the instrument places. And in 2016, she released Sunaadham: The Vikku Bani of Ghatam Playing, a guide to learning the ghatam. In addition, Ramgopal also advocated on behalf of the ghatam with the Sangeet Natak Akademi. With the recent demise of Meenakshi Amma, the leading ghatam-maker from Manamadurai, she impressed upon the Akademi the need to encourage the younger generation in the village to keep the art and skill of ghatam-making from decline, signs of which have been evident for some time. Her efforts have paid off; “the Akademi has now given a grant for training people in ghatam-making,” she reveals.

The recipient of several awards and titles, Ramgopal prefers to mark her musical journey with emotional milestones. One such moment came in 1996-97, when she accompanied vocalist M S Sheila on a three-month concert tour in the US. Following a concert at Cincinnati, a certain Mr Natarajan who spoke at the end of the concert lauded Ramgopal on her performance and said that, through her, U V Swaminatha Iyer had been reborn to pick up the strands of music from where he had left off. “That was a moment of great pride for me and I felt humbled to be compared to such an illustrious person as my great-grandfather,” she remarks, her eyes welling at the memory even after all these years.

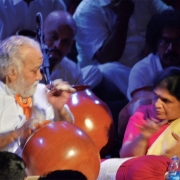

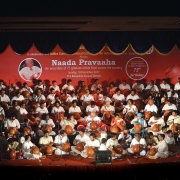

Gratitude can be expressed in many ways; for Ramgopal, paying a rich and grand tribute to her guru Vinayakram was her way of saying ‘thank you’. On 10 December last year in Bengaluru, she marked his 75th birthday with a percussion ensemble involving—hold your breath—75 percussionists from all over India! The concert, a first of its kind, lasted three-and-a-half hours and, not surprisingly, received rave reviews.

WHAT IS A GHATAM?

The ghatam or ‘pot’ is an ancient percussion instrument in South India. The madga of Rajasthan, matka of Gujarat and ghara of Punjab are variants of the ghatam, used in the folk traditions in these states. While essentially an earthenware pot, it is made sturdy by mixing the clay with small amounts of brass, iron or copper filings. The addition of these small metallic shards produces the distinct metallic sound associated with the instrument.

While the pitch of a ghatam varies directly with its size, it can be altered by applying water to its neck. To ensure good tonal quality, the walls of the pot must be of even thickness. The player usually places the ghatam on his/her lap, with its mouth facing his/her belly. Performers use their fingers, thumbs, palms and wrists to strike its belly, neck and rim, to produce the different sounds. In fact, by continuously pressing and opening the ghatam’s mouth against the player’s belly, a range of sound modulations can be produced. However, there are variations in the way the instrument is placed, with several players, especially women, keeping it on a ring or a stand in an upright position.

THE GHATAM MAKERS

Manamadurai, a small village near Madurai in Tamil Nadu, is the most important centre for the manufacture of ghatams. There are smaller centres where the instrument is made, in Chennai and near Bengaluru. In Manamadurai, four generations of a single family have been making the instruments for over a century, with the fifth generation only just beginning to shoulder the mantle. A third-generation veteran, 67 year-old Meenakshi Amma passed away in November 2017 and is perhaps the only instrument-maker to receive the Sangeet Natak Akademi award.

Ghatam-making is an arduous task that takes several days. It is only after the pot is baked that one can know whether it is ‘music-worthy’. The outer surface of the pot requires hours of tapping with a flat wooden hammer while the other hand remains inside the pot, holding on to a specially made, heavy stone. Only roughly 40 per cent of pots that are fired turn into usable ghatams with good tonal quality. As much as 16 kg of raw clay is beaten and fired, resulting in one ghatam, which is eventually half this weight.

Meenakshi learnt the art of ghatam making from her husband and father-in-law, at the age of 15. Her son Ramesh, who has taken over the business, has already initiated the fifth generation of Manamadurai’s ghatam-makers by training his daughters, niece and nephew. The family turns out about 400 ghatams per year, only half of which are sold because the rest fail the tone test.

Photo: J Ramaswamy Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine April 2018

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….