People

From ageing mummies to crumbling murals, Mumbai’s ‘art doctor’ uses out-of-the-box solutions to preserve our artistic and cultural legacy

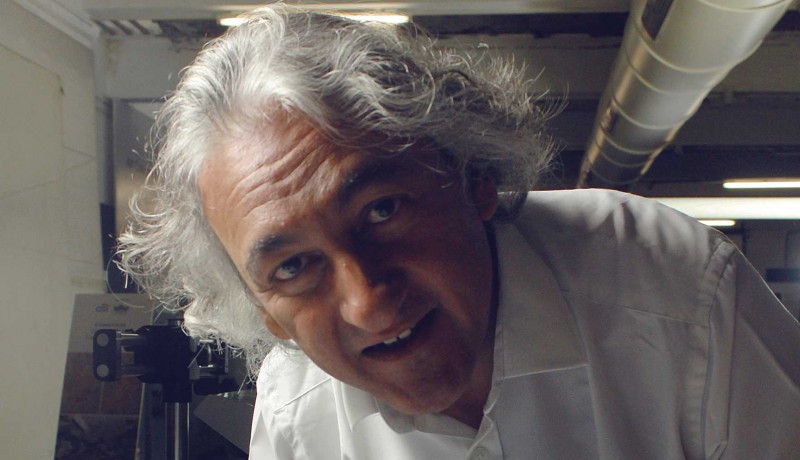

In the Key gallery of Mumbai’s Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vaastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS), two bronze statues have made a conspicuous disappearance. A 10th century Buddha from Nagapattinam, Tamil Nadu, and an 8th century Bahubali from Karnataka are being transported to the Museum Art Conservation Centre to be treated for a turquoise-coloured mold that was found growing out of them. There, Anupam Sah, head of the conservation centre, awaits their arrival.

With gloved hands, he delicately places the statues on the operation table, beneath a large box light, and examines the mould through a microscope. It looks like they have contracted a corrosive “copper disease” owing to the moisture and minerals in the air. “The disease is eating away at the statues from the outside in, so we’ll have to scrape it out and use corrosion inhibitors to treat it,” Sah tells us.

Sah is one of India’s leading art conservators and restorers, who shot to the spotlight a couple of years ago, when his work on a 4,500 year-old Egyptian mummy made the news. “But people were rather disappointed to see the mummy all covered up. Earlier, there were pieces of toe and head sticking out,” he chuckles.

The mummy of princess Naishu, purchased by a relative of the Nizam of Hyderabad, had been spoiling away at Hyderabad State Museum since the 1920s. While Sah’s restoration efforts made for juicy headlines, he remains unfazed. “The first thing they teach you is to not get excited because you have to do objective work. You never allow your own artistic opinions to overpower your sense of propriety when treating someone else’s work. You have to use your skills and sensitivities to do just what is required,” says Sah, who has been knighted by the Italian government in recognition of his work.

When a 100 year-old wall painting at the Jagannath temple of Dharakote in Orissa was falling off the wall, the plaster on which the 20-ft painting was done was so unstable that Sah and his team could not directly intervene. “We needed a few days to just sit down there, to feel the material and its layers before we arrived at a treatment plan,” he says. They mounted a scaffold close to the wall and rolled layers of fine muslin cloth over the wall. Through the muslin, they administered their consolidation injections, which would bind the plaster back onto the wall and hold the painting in place.

Despite his fascinating achievements, Sah is even more proud to have worked on bridging the gap between heritage conservation and development, through his work as a teacher and trainer. As we speak, his team is readying the office computer for a video conference with students in Nainital, his hometown, where he runs a manuscript conservation centre under the Ministry of Culture’s National Mission for Manuscripts. “Over 100 people have been trained here in the past eight years,” reveals Sah, whose formal qualifications include a bachelor’s degree in science and a master’s degree in art conservation.

He has also worked on reviving the wall painting tradition of Orissa in Raghurajpur, which was then declared a heritage village, and has trained stone sculptors under the Old Town Revitalisation project near Bhubaneswar, which encourages local government agencies to employ locally available artisans and craftspeople in civic projects. “You just need people to start things off; if it’s a good idea, people catch on.”

In Ranibagh, near Nainital, Sah has set up the Himalayan Society for Heritage and Art Conservation, or HIMSHACo. Now in its 13th year, the organisation trains people, especially in the hinterland and across mountain regions, in wood and stone carving, paper work, darning, etc.

Of all his projects, this one remains closest to his heart, for this is where it all started. It was at his grandfather’s place in Ranibagh, as a boy of 13, that he decided he wanted to be an art restorer. “I read an article titled, ‘How science cures the ailing art’ by the Central Institute of Restoration in Rome. It spoke to me. Right then, I knew I wanted to do something that was an amalgam of the sciences and the arts.” He wrote them a four-page letter, learnt the Italian, and followed his dreams all the way to Italy. Then, he returned to commemorate the place where it all started. “That’s providence,” he smiles.

—Natasha Rego

- AMAN NATH

- C SEKAR

- DINESH DESHPANDE

- INDRA VIJAY SINGH

- MOHAMMAD IMTIAZ & REYAZ

- SAILAJA PATURI

- SANDEEP KATARI

- SHASHIKANT MAYEKAR

Photos: Natasha Rego Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine October 2018

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….