People

Master batsman and former Indian captain Sunil Gavaskar, who has remained on strike with his management company and role as commentator after retirement, shares his remarkable journey with Neil Joshi

He arrived on the scene with a bang at the age of 17 when he was named ‘Best Schoolboy Cricketer’ in 1966. Sunil Manohar Gavaskar’s style of batting and stroke-making sent the bowlers fetching and left the audience in awe. If there was anyone in the Indian team who could prove a match for the ‘fearsome quartet’ in the Caribbean Islands, it was the ‘Master from Mumbai’.

Gavaskar was under the tutelage of his uncle and former cricketer Madhav Mantri, which meant he aimed to be as close to a perfectionist as possible while always being able to stoutly put a ‘price on his wicket’—he recollects how his uncle once berated him when he threw his wicket away after scoring a double ton. When he arrived on the big scene, Gavaskar was made to wait for a good two years before he was selected as a member of the Bombay Ranji squad. So fierce was the competition then, that all he wanted was a match or two to show his prowess. When he finally got the opportunity, he didn’t disappoint—Gavaskar soon made his way into the Indian team and was sent on a jet to the celebrated tour of West Indies in 1971. The ‘Little Master’ had arrived and his critics were silenced.

Part of the first World Cup winning team, which stands at the top of his personal list of achievements, Gavaskar also played in the prestigious World XI squad, which included the greats of the era, and was chosen by Sir Donald Bradman himself. The original Indian ‘Wall’ went on to break his record for the most centuries (he had the highest of 34 tons and was the first to surpass Don Bradman’s 29). After being eulogised for his dexterity on the field, he took to the mike—over a period of three decades, he has become the voice of Indian cricket, on radio or television—and ‘played straight’ with his columns. Now, 69, Gavaskar looks back on his career, travels, his partnership with his family, and his love for his favourite sport: badminton! Here are some excerpts from an exclusive interview.

SUNNY THE ‘BUSINESSMAN’

It’s been over 33 years for Professional Management Group (PMG). Was it a risk to venture into this sphere, especially during your playing days, and has your decision to enter management been vindicated?

To sustain the company and make it what it is, more than 90 per cent of the work was done by Sumedh Shah. We started the company in October 1985. We were earlier into player management and got off that as it wasn’t an easy stream at that time. We then focussed on columns and TV programmes and got into golf and tennis. We came back into player management 10 years ago. Today, PMG is what it is owing to the huge contribution of Sumedh. Now, Sam Balsara and N D Mehta are partners in the company.

As a sportsperson, where jobs were far and few, you were associated with companies like ACC and Nirlon. After that, was it a conscious move to get into player management?

Cricket wasn’t a career in those days; if you were a half-decent cricketer, it got you a job in a corporate entity. The Times of India Shield used to be huge and there were lot of corporates who participated and got mileage if their team did well. Players playing in the ‘D’ division could showcase their potential. Companies like the Tatas would have their best team in the ‘A’ division but one of their teams would also play in the ‘D’ division. So one needn’t be playing for India or Ranji Trophy; even if you were a good club cricketer, you could land a job. Those jobs meant you would work till your retirement age of 60.

You have been the Indian voice in the international arena for the past three decades; what prompted you to take a role behind the mike?

I think I was lucky to be in the right place at the right time. It was 1990 and Sachin Tendulkar had got his first century in England. At that stage, too, it didn’t look like I wanted to do commentary. Also, I didn’t want to travel the world for matches that didn’t involve India. I was clear in my mind about that. Then, India went to Australia and I was invited to do commentary for Channel 9. When cable TV came into India, BCCI won a landmark case against Doordarshan and broke its monopoly; the cricket board was paid for the broadcast rights to show the 1993 England tour of India. From there on, it became a second profession for me. PMG is still my primary profession.

You are regarded as India’s first ‘Little Master’. How did that moniker come about?

The ‘Master’ was first used for Jacks Hobbs. He scored 197 first-class hundreds and 100 of those came when he was over 40. Those were the days when people played on uncovered pitches; achieving this feat was incredible. Hanif Mohammed from Pakistan batted for three days to get his 337 against the West Indies. At that time, it was the English winter. All the English writers were trying to avoid the winter at home and went to the Caribbean to get the ‘sun’ and ‘cricket’; one of the writers called him the ‘Little Master’. So after that, whoever was short and scored well was given that title! The original one was Hanif Sir.

LITTLE BUMPS & EARLY STRIDES

You waited almost two years to get into the Bombay squad and were on the sidelines for most of that time. How difficult was it to cement a place in the Ranji team?

It was very difficult to get into the Bombay team. You had eight to nine players in the national side from Bombay. So, the popular talk in those days was, “It is easier to get in to the Indian team than the Bombay team.” I understood it wasn’t going to be easy and that I may get a match or two in my entire career. I had to prove myself to know whether I belonged there.

I played one match for the Irani Trophy, which was against the Rest of India; 21 players were vying for a place in the India team to go to Australia, for which the squad was going to be announced after the match. I was the 22nd player and didn’t consider myself in contention; I failed in both the innings. After that, I didn’t get an opportunity to play for another three years despite scoring runs for clubs and inter-university cricket. That’s how Bombay cricket was and I am not complaining about the fact I wasn’t chosen. There were players who were scoring runs in the Bombay team who couldn’t be dropped.

By the time you cemented your place in the Bombay team, you must have learned a lot from your travels with ‘greats’ in the team. Could you shed some light on your travels and how they helped you become a better cricketer?

The Bombay Cricket Association (now Mumbai Cricket Association) took care of the players very well. We travelled first class and virtually got the entire bogie to ourselves. This was because we were the champions. Unlike now, where the support staff outnumbers the players, we had just one manager and a masseur. There was a great bonding experience. Suppose we travelled to Calcutta, we would spend two nights in the train and it was fantastic for the simple reason that the youngsters and seniors would congregate in one cabin. The youngsters would lie on the upper berth while the senior players would sit below and play cards to pass time. Even while they were playing cards, we would be talking cricket, there was a bit of leg-pulling—we were soaking in all the experience and knowledge. This also meant we could see the greats as pure ‘human beings’. Sometimes, one is overawed by them but luckily that didn’t happen to us because they showed us their personal side. They would be sitting in shorts or lungis or wearing a plain ganjee [vest]; when you see someone in very casual attire, all the formalities seem to be broken. I would recommend it to anybody! Even touring in a team bus was a great bonding experience, especially when we were touring in England. Where is a chance to do something like this in an aircraft?

Who were your mentors and what did you learn from them?

When I played for Dadar Union [Matunga, Mumbai], I had my uncle Madhav Mantri [who started Dadar Union], V S ‘Marshall’ Patil, Vasudev Paranjpe, Ramnath Kenny, Narayan Pai and Naren Tamhane around. When we met, we could see the discipline in them. Whoever you were or however popular, if you didn’t come half an hour prior to the match and if you came a minute after 10 am, you were dropped. They mentored us by telling us to keep our shoes white, our leg-guards white. There was no issue about getting your clothes dirty on the field, but then you had to wear your whites the next day.

Please tell us more about Madhav Mantri as an influence on your career.

Both he and my father Manohar were huge influences on me. I make a mention of Madhav Mantri at almost every corporate event with regard to my playing career. Our residence was at a distance from his and we would visit him only once in two to three weeks. But when we shifted closer during my first year of college, I remember going to his house very frequently. One day I opened the drawer of his cupboard and saw a lovely woollen sweater. There were also so many caps. So I asked him, “Can I have this cap? You have so many of them.” He said, “No, I can’t give it to you. You have to earn it. These are the caps I have earned. Unless you earn it, you can’t get this cap.” These words had a profound impact on me as they taught me the value of hard work and not getting things easily in life. Today, you can get the Indian cap easily owing to merchandising as well as counterfeiting. It’s available for ₹ 100 on the street. I really feel sad about it. In Australia, the merchandise available for fans is different from what is worn by the players. Everything remains the same, but the logo is different. There is a distinction; it has to be earned.

We believe your mother would celebrate every ton you scored by gifting you some money….

At the end of the series, my mother would give me a rupee for every run I scored. So if I scored 500 runs in a series, my mother would gift me ₹ 501 in an envelope. Despite shifting residences, I have most of those envelopes unopened and in the old currency. It was more like a blessing. My father would treat his colleagues at his office with sweets every time I scored runs.

You have often been compared to the great Sir Donald Bradman. Could you share the incident when ‘three Bradmans’ converged at one place?

It is huge honour to stand on the same pedestal with Sir Donald Bradman. Nobody can be compared to him; he was such a phenomenon. Nobody in the game will ever come close to his average when they finish playing cricket, nor to the consistency with which he scored his runs. His appetite for double and triple hundreds, whether playing first class or international cricket, was immense. We were part of the Rest of the World (RoW) team that travelled to Australia in 1971-72. The Australian government had cancelled the tour of South Africa owing to apartheid and we had come to fill in the season. I was in the RoW team with Sir Garfield ‘Gary’ Sobers. In those days in Adelaide, you got off the tarmac and walked to the airport. Sir Bradman, who had picked the RoW team, was waiting for us and especially for Gary Sobers, whom he got along very well with. Bradman asked Sobers, “Where is that little fellow from Bombay?” At that time, Zaheer Abbas, who was also in the team, also came forward to meet Bradman. The good old Rohan Kanhai saw that and exclaimed, “Here is the ‘Bombay Bradman’, there is the ‘Karachi Bradman’ and here is the ‘Real Bradman’!”

SKIPPER’S CAP & THE CUP FOR LIFE

Did you enjoy your captaincy? How important was it to be in form to get the best out of your boys?

It was enjoyable 95 per cent of the times. You won’t find it enjoyable if you are not pulling your weight in the team. I could not ask the players to do things when I was not doing well. It was not difficult to motivate the players at all. We were among hundreds of players vying to be in the Indian team. None of us took it as a privilege; we never took it lightly.

The 1983 World Cup was a big win…..

The World Championship in 1985 was close to being on a par with the World Cup. But the World Cup is the World Cup. That win cannot be compared to anything. That was the greatest moment of my career; that win still gives me goosebumps. Nothing can match that win and nothing comes close. It was a magnificent moment to watch Kapil Dev lift the Prudential Cup on the Lord’s balcony. We were happy to have hundreds of Indians thronging the ground after the match.

LOOKING BACK

You have enjoyed close rivalries against teams, some of them really intense. Which teams you would identify as the fiercest in your times?

Clearly, the West Indies and Australia were the teams you always wanted to do well against; so was Pakistan. Sri Lanka wasn’t a Test playing nation until the last couple of years of my playing career. Pakistan had some great players in the 1970s. I cherished playing against Pakistan but, most important, I got to learn something new from every game.

Was retirement a tough decision or could you see it on the horizon?

I got the message almost a year earlier. In the last couple of years of my playing career, I was looking at the clock around teatime and saying to myself, “Another 20 overs of fielding till the end of play.” That is when it struck me that I wasn’t enjoying myself on the field. And when the time came it was easy for me to take a call on retirement. [Gavaskar played his last Test against Pakistan in Bengaluru in March 1987 and his last ODI versus England in Mumbai on 5 November 1987 in the World Cup semi-final.]

Surpassing Don Bradman’s 29 centuries would be one of your most cherished moments….

I would imagine so. Initially in my career, to share a dressing room with some of my heroes like M L Jaisimha, Salim Durani and Ajit Wadekar and then playing my first series against the likes of Rohan Kanhai and Gary Sobers was unbelievable. I met ‘Don’ in my first year of international cricket in November 1971 when I toured Australia after England and West Indies. It was a tremendous learning experience.

Who was the best skipper you played under?

I enjoyed playing under Ajit Wadekar. When I started playing for Bombay, he was my skipper, and also when I made my debut for the Indian team. Ajit as a captain was tremendous and had his own methods of doing things. He often used Eknath Solkar and me to pass the message to others. He would scold us to make others aware despite us doing nothing. As we were Mumbai boys, he could say things to us. He would later come and tell us that the message was meant for someone else! Look at the success he had in the West Indies and England—he was the first captain to register India’s first wins in those two countries. I played under six to seven captains but Ajit was the best.

THE ‘SUPER’ STAR

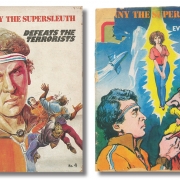

How did it feel to be part of the comic strip, Sunny The Supersleuth?

I was pleasantly surprised to see a comic strip few days ago when someone came up to me for an autograph. I was seeing that after a long time. I would like to get hold of the copy. I know that I am comfortable flying but superheroes go all over the place and fly like a rollercoaster or a giant wheel—I don’t think I can do that!

Did you ever feel your story should be documented in a movie?

My life has been quite well-documented. There hasn’t been much documented on Dhyan Chandji. If someone should be on the silver screen, it should be him. I don’t think my life needs to be documented!

THE ‘BETTER’ INNINGS

How often did your wife Marshneil accompany you on tours? Did she have to take a backseat while you were travelling with the team?

I preferred to take my wife everywhere, wherever I toured. The BCCI didn’t tell us officially but they generally didn’t want wives to be a part of the first half of the tour because that is when you are getting into the groove and you have certain official functions, like visiting the Indian ambassador at the embassies. When I got married, I was a vice-captain and got a room for myself. So she could stay and it would not disturb anybody. Later on, when I stepped down from captaincy and had to share a room, there was a question about how to adjust. I wasn’t the only one with a wife on tour. To accommodate our partners, we would request the fast bowlers for their rooms. The Kapil Devs, Madan Lals and Karsan Ghavris wouldn’t sleep on the bed; they slept on the floor to rest their backs. So we had to request them early for their rooms—100 times out of 100, they accommodated us!

How do you spend a regular day now?

I usually take it very easy, sleep and read a bit.

It’s hard to believe that badminton is a sport you rate over cricket!

For me, the No. 1 sport is badminton, over and above cricket. I used to play till five to six years ago. I didn’t have the legs and lungs to play singles as a profession. I think it’s a fabulous game that requires high skill and stamina. Now, fitness has become an integral part of the game. If you see the rallies, they are 40-50 strokes, which is just amazing. Cricket is my life and what I am is because of cricket. However, had I not made my mark in cricket, I would like to have done so in badminton.

LIFE TODAY

What’s it like to be a grandfather?

The best hat I wear now is that of a grandfather. It’s an education in itself. When you spend time with your grandkids, it’s a big stress-buster.

You are not known to be a foodie….

There are only six to seven days of the year when I eat like a pig! The rest of the year, I eat very little. I am a small eater. I am not a good guest to have at one’s home. Generally, the hosts feel I haven’t liked their food because I eat such small portions. That’s probably the reason I have stayed so small!

Would you have found a place in the team today?

I don’t think I would have found a place in the present Indian team. The game today is far more entertaining than when we played or even before we played. There are so many shots being played; second, the players are so fit, athletic and agile. It’s a delight to watch them throw themselves on the field, run fast between the wickets and hit the big shots. There has been a lot of innovation in shot-making, like scoops, switch hits, etc.

Do you believe cricket is a batsman’s game?

Cricket has always been a batsman’s game. But it’s the bowler who gets six deliveries; even if he is hit for five sixes, he waits for the batsman to make one mistake and sends him back to the pavilion. That said, even though the sizes of bats have been changed recently, batsmen are strong now. They go to the gymnasium and pump weights. The sixes they hit out of the stadium are also because of the quality of the bats.

Why were you reluctant to coach the Indian cricket team?

I will be very honest: I am not a good watcher of the game. Even when I was playing, I wasn’t a good watcher. Suppose I got out early, I would come into the dressing room and read a magazine or novel or reply to letters and then go out and watch the game. I wasn’t like G R Vishwanath or like my uncle Madhav Mantri; they were ball-by-ball watchers. I wasn’t ever that and still am not, even when I am doing commentary. If you are not a ball-by-ball watcher, you cannot be a coach or a selector. It is only when you focus that you can assess a bowler or batsman. I am unable to do it and hence cannot be considered for a selector—or even give it a thought.

Looking back, would you do anything differently?

I have absolutely no complaints from life. I have been very blessed; I am very happy and content. I used to tell everyone my ambitions were on the field of play. Off it, I have none. I have still not retired and I am still batting. As long as ‘He’ keeps me blessed, I will bat.

Photos: Haresh Patel Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine November 2018

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….