People

In Mumbai, Jyoti Mhapsekar is working towards an unusual utopia—zero-waste management—while empowering slum women, writes Natasha Rego

Eighteen years ago, NGO Stree Mukti Sanghatana (SMS) staged a skit in a slum in Chembur, aimed at spreading word of a day-care centre for 25 little girls in the vicinity. Titled Mulgi Zali Ho (It’s A Girl Child), the skit by Jyoti Mhapsekar was meant to urge women to keep their kids at the day-care centre while they earned their daily wages.

Mhapsekar, the 69 year-old founding president of SMS, had no idea then that this gesture would lead to empowering thousands of slum women in Mumbai. It also started a revolution of sorts, in waste collection in this metropolis.

“We had already been working with women from economically backward strata for about 20 years but we did not know that the women of that slum were primarily waste pickers at the Deonar dumping ground and street-side garbage bins,” says Mhapsekar, recollecting that fateful day.

That realisation inspired SMS to launch the Parisar Vikas programme, now with 3,000 members, which trained waste pickers in the collection, segregation, composting and disposal of waste from housing societies, corporate campuses and hospitals across Mumbai. Apart from helping them find employment in this way, SMS also empowers them with life skills, offers them regular healthcare, and provides educational facilities to their children, especially the girl child.

“When we learnt these women were waste pickers, we decided to meet more of them,” Mhapsekar recalls. But finding them was a challenge. “We had to hang out near garbage bins where a couple of women would be working and ask them to take us to their community. That way, we acquainted ourselves with about 2,000 of them over the next couple of years and surveyed them. We wanted to know who they were and where they came from.”

SMS discovered that these women were unskilled Dalit migrants who had fled drought-prone Marathwada. Eighty-five percent of the waste pickers they had surveyed were women, many of them single, which made them primary breadwinners. Apart from earning a pittance from waste picking, they were prone to respiratory diseases, skin infections and rat bites, for which they received no medical attention. Their survey also revealed that these women were an ever-growing force in an ever-growing city; if the NGO was to empower this invisible workforce, they would also have to capitalise on the garbage itself.

“When we started Parisar Vikas, we thought we’d only have to work with the women. But for true liberation from waste picking, we realised we would have to start learning about garbage too!” says Mhapsekar, a former librarian by profession. So, SMS educated itself on garbage segregation and its members attended composting workshops. It then educated the women about government schemes, childcare techniques, nutrition, sanitation, girls’ education and age of marriage.

The NGO also engaged an expert to train the women in zero-waste management. “As they couldn’t forego even a day’s earnings, we gave them a stipend,” says Mhapsekar. “We needed to wean the women away from the dumping grounds and garbage bins. By the year 2000, SMS had trained about 1,000 women in waste segregation, dry-waste collection and composting.”

The challenge then was to find these women formal employment via contracts with housing societies, to maintain zero-waste premises. This involved door-to-door collection of segregated waste, maintaining a compost pit in the compound, and sending dry waste for recycling. It also meant convincing individual, middle-class households to segregate their waste at source. This is a hurdle Mhapsekar still deals with today. “One of the first housing society contracts we got was at Makarand Sahaniwas in Mahim,” she shares. “Some of our supporters living there had a tough time convincing their fellow members.”

Arun Kumar, CEO of Apnalaya, another NGO that works with marginalised communities in Mumbai, including waste pickers, remarks: “The municipal corporation may not be doing its part to ensure that waste is segregated and collected, but when it comes to citizens, the mindset still relies on the age-old caste system; we assume that there will always be ‘someone else to pick up my rubbish’.”

“As affluence increases, garbage also increases. But the middle class feels it is the business of the poor and lower caste people to take care of it. I would attend general-body meetings of housing societies to meet the residents and dispel their concerns,” says Mhapsekar. “Even if they were interested in managing their waste, they would be worried that the compost would smell. So I would make a speech, screen a film and distribute pamphlets on garbage.” After much convincing, four housing societies in north-east Mumbai made deals with SMS—the organisation had to take care of the business transaction and assign trained women to each society.

Although this was an encouraging start, there were a few stumbling blocks. In those days of scant mobile connectivity, keeping track of so many women came with certain hiccups. Mhapsekar recalls the time when the women did not show up to work at one large housing society. “Our phones were ringing with the voices of angry residents and we had no idea why they were all absent. So we went to their homes and found that someone had died and everyone had stayed back to show support. We had learnt a valuable lesson that day, that each group needed to contain women from at least two different slums.”

In 2004, SMS took the next step and began to organise the women into cooperatives under the Parisar Vikas programme. They began to call the women ‘Parisar Bhaginis’. By now, their activities had expanded to Wadala on one side and Bhandup on the other, and the housing society contracts were transferred directly to these cooperatives. “We wanted them to take independent charge of the business transactions,” says Mhapsekar. “We would only step in to negotiate the deals.”

Today, SMS has 10 cooperatives, with about 50 members each, maintaining zero-waste properties at 70 housing societies in Mumbai, as well as a residential colony of the Reserve Bank of India. The corporates they work with include Sony, Voltas, Godrej, Bajaj and Cap Gemini in the city.

In fact, in December 2016, Vijaynagar Cooperative Housing Society in Andheri, under the wing of SMS’s Ramai Cooperative, won the ICICI Bank Swachch Society Award for its zero-waste premises. The Parisar Bhaginis also collect the non-medical dry waste from six hospitals and two malls and transport it to the five dry-waste sheds they acquired through a government welfare scheme. Those who are not in the cooperatives belong to one of SMS’s two federations that comprise 1,500 self-help groups that enable the women to borrow money from each other instead of moneylenders.

Over the years, many women have been promoted to positions of supervisor and trainer, and now handle the contracts, in addition to training fellow waste pickers. One of the first members to join SMS, Susheela Sable has come a long way from drought-prone Marathwada. The 50 year-old president of one of the federations, who was waste picking since the age of 10, has become a spokesperson for waste pickers at climate-change conferences across continents. In 2009, she addressed the Copenhagen Climate Change Conference in Denmark for the first time. “I like to give them a picture of our situation and dispel certain myths. It is true that there are so many slums in India… but as waste pickers, what sense does it make to keep our own surroundings dirty when it is our duty to clean up the city!” she points out.

As for Mhapsekar, who was awarded the Nari Shakti Puraskar by President Pranab Mukherjee in 2015, the ultimate objective of SMS is to work towards eradicating waste picking altogether, something that can happen only if Mumbai segregates its waste at source, i.e. at home, and disposes of it in a scientific and sustainable manner, as laid out by the Central Government’s Solid Waste Management Rules of 2016. “Yes, legislation has been introduced but, on ground, everything remains the same,” rues Apnalaya’s Arun Kumar, whose organisation works with about 500 waste-picker families near the Deonar dumping ground. “There is increasing pressure on residential colonies to segregate their waste. But then we see municipal collectors dumping it all into one truck. There is no systemic effort to ensure that garbage is segregated, the process is decentralised, or that anyone who violates the rules is punished.”

The 2016 rules also ordered the integration of informal waste pickers into the city’s collection of residential solid waste. But both Mhapsekar and Kumar are reluctant to give the municipal corporation many points for this. Making matters worse is that the city has only three dumping grounds, of which the “mountain” at Deonar should have been closed 50 years ago. So it will be a while before Mumbai can be considered a clean and green city.

“However, if that day does come, 25,000 waste pickers will be out of work,” says Mhapsekar. “So they should be given alternative skills, like sorting in dry-waste sheds, and we must ensure their future generations do not fall into the same cycle.” There are stories of hope in this regard. For instance, some women, like Mangal Thorat, have made use of the opportunities SMS provides to turn their life around. When her son, enabled by SMS’s education programmes, wrote his Class 10 exams in 2010, the former waste picker joined him and completed her Class 10 exams too. She went on to become a part-time nursery school teacher and part-time trainer with SMS.

With the NGO’s reach spreading to neighbouring municipalities, Mhapsekar’s mission with SMS is almost coming to an end. “I turn 70 in two years and it will be time for me to take a backseat,” she says. “But next year, we want to extend the concept of zero-waste campuses in colleges. To catch them young, we’re going big, with poster exhibitions, films and street plays. We’ll also take a mobile garbage exhibition, which the EU helped us set up.”

Regardless of how much longer she stays at the helm, Mhapsekar is always thinking up ways to achieve SMS’s ultimate goal. Clearly, there’s no time to waste.

THE WASTE FACTSHEET

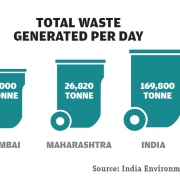

- According to the India Environment Portal, run by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), India is the world’s third-largest garbage generator, after the US and China, generating 169,800 tonne of garbage per day

- Maharashtra, which is the state that produces most garbage in India, generates almost 15 per cent of the country’s trash (26,820 tonne per day)

- Mumbai, which produces 9,000 tonne of garbage per day, is the city that generates most waste in India

- Indore in Madhya Pradesh has been ranked the cleanest city according to the Swachh Survekshan 2017, which takes into consideration waste segregation at source and integration of waste pickers into the system

- In February, the Tirunelveli Corporation received the ‘Best Corporation Award’ by the Centre for its efficient collection and disposal of segregated waste

Photographs courtesy: Jyoti Mhapsekar Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine June 2017

AGRICULTURE

FORESTS

WILDLIFE

WATER

ENERGY

SUSTAINABILITY

EXCLUSIVE COLUMN

EXCLUSIVE COLUMN

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….