Columns

Raju Mukherji on the legendary hockey player Dhyan Chand, who shone on and off the field

No Indian has heard of Dhyan Singh, the sportsman. But every Indian has heard of the legendary Dhyan Chand. Both names actually belong to the same person—one fine evening, Singh became Chand! Why and how did that happen?

The story is perhaps apocryphal but there is a distinct authenticity surrounding the circumstances. When his regiment slept at night, a young subedar would pick up his hockey stick and practise alone. His commanding officer, a Britisher, watched him intently under moonlit nights and marvelled at the man’s perseverance. As Dhyan tore into oppositions during the regimental matches, the officer went into ecstasy, “Chand ka tukda.” And the name ‘Chand’ stuck.

Born in Allahabad in 1905, the young Dhyan was a wrestling fanatic who idolised ‘The Great Gama’ Pehelwan (Ghulam Mohammad Baksh). But he followed his soldier-father, who played hockey for the regimental side, and had settled down in Jhansi. Coming on as a substitute in one encounter, he caught the eye of a British army officer, was drafted into a youth team, and the saga of Dhyan Chand began.

Sobriquets like ‘wizard’ and ‘magician’ followed his exploits. His non-conformist techniques staggered the world. For his part, he was a martinet; his principles and sense of patriotism bordered on lunacy. When Adolf Hitler offered him a field marshal’s post in Germany, he politely declined. Dhyan Chand was an ardent Indian patriot who could not visualise serving anybody but his motherland. He was the original ‘Dada’ of Indian sport.

For him the nation came before self, family and friends. At a time when he was in dire financial straits, Australia offered him a coaching assignment. Again, he refused because he felt that if his coaching led to Australia defeating India, he would not be able to hide in shame! He sacrificed financial security for himself and his family for the cause of his motherland. In these days of match-fixing and bribery, Dhyan Chand would appear to be of unsound mind. In truth, he was the opposite; he exemplified the difference between a patriotic professional and a low mercenary.

Dhyan Chand had a wide repertoire of hockey skills but he never played to the gallery. On the contrary, he used them for the benefit of his mates and his country. His early coach Bhole Tiwari, whom he addressed as Guruji, drilled into him that hockey was a team game and no individualism would be tolerated. No unsavoury incident affected him. Every obstacle appeared to inspire him to further laurels.

On his first trip with the India team in 1926 to Australia, his artistry made him a celebrity as he scored over 100 goals and helped others to convert many more. But the India captaincy eluded him both in the 1928 and 1932 Olympics—because he was a ‘commoner’ by birth.

However, by the Berlin Olympics in 1936 the crown was deservingly on him. With or without it, he was the king of the game. Still, despite three gold medals in three Olympics, he and his mates made no financial gains as the amateur ideals were very strictly enforced at the Olympics in those days.

World War II shortened his career. Nevertheless, his genius was acknowledged far and wide. His statue came up in Vienna. India accorded him the Padma Bhushan and, after his death in 1979, a postage stamp was issued to honour him. In 1995, a statue was installed in New Delhi, the first for any Indian sportsman. And his birthday, 29 August, is celebrated as National Sports Day.

On the Padma Bhushan presentation day, Prime Minister Nehru asked him, “Dada, you have so many medals. Please give me one so that I can also put it on my chest and look like a sportsman.” Dhyan Chand replied, “Panditji, on you only the rose looks good.” Such was his sense of honour. He did not believe in gifting away hard-earned awards to people who did not earn them. Can you imagine a sportsman today refusing the PM’s request in such a cheerful manner?

In Pankaj Gupta, the mercurial manager of the India hockey team, he found a friend-philosopher-guide. Dhyan relied on Gupta on various off-the-field issues. At the time India played under the British flag. Dhyan Chand later recounted, “Before the Olympic final against Germany in 1936 we were a little nervous, having just lost to them in a friendly match. But our manager suddenly produced a Congress tricolour and told us this was a fight for India’s independence. The players, comprising Christians, Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims, became highly motivated. We saluted the flag, prayed, and went out to fight for our motherland.”

Normally, geniuses are highly individualistic and prefer to draw the entire focus on themselves. But Dada was different. He was a team man who helped others excel. He relied on discipline and selflessness. Once he rebuked his brother, the brilliant inside-forward Roop Singh, for being selfish at play, “Kishen, you may leave the field since Roop has decided to play in your position as well as his!” The irony was not lost on Roop Singh, and the message was clear to the entire team.

Today, we hear hockey has declined in status in India because there is no money in the game. This was the case in Dhyan Chand’s days as well—but no one raised this issue when India was winning gold in the 1928, 1932 and 1936 Olympics. When Dhyan was asked about the lack of monetary support, he laughed: “We were not playing hockey to earn money. We were playing for India’s glory.”

Once, in 1937, actors Prithviraj Kapoor and K L Saigal came to watch Dhyan Chand and Roop Singh play. At half-time the score was nil. Saigal commented, “I have heard so much about you. Surprised to see that you are unable to score a single goal.” Dhyan replied, “Will you sing as many songs as we score goals?” Saigal nodded in agreement. Dhyan and Roop scored 12 but by then Saigal had left the field for some urgent work. However, the next day, he invited the team to dinner, regaled them with his enchanting voice, and presented every member with a wristwatch. Different era; different values.

After Independence, the great man was generally ignored by the people who administered Indian hockey—no one thought that he would be able to contribute in any way! While his protégé Shah Dara was doing wonders for Pakistan as an administrator and coach, here in India we had no time for the greatest ever hockey player the world had ever produced. Once, Dhyan Chand was given a coaching stint in Patiala. While he was showing his deft stick-work, Indian Hockey Federation (IHF) chief Nagarwala intervened to show Dhyan the correct way! Dhyan, ever the gentleman, politely asked him to take over the coaching assignment. Within a few days, Dhyan was asked to put in his papers. That was the end of his coaching career in India.

After the 1971 war with Pakistan, the first sports contact between India and Pakistan was in 1974. Indira Gandhi was advised by Siddhartha Shankar Ray, her cabinet minister and a former cricketer, to use the image of Dhyan Chand to renew India’s relationship with Pakistan. Immediately an Asian all-star team was invited to come and play on Indian soil. And the great Shah Dara arrived to pay his unbounded respect to his mentor.

The last person to interview Dhyan Chand happens to be the scholar-journalist Tapan Ghosh. According to him, at a tea reception hosted by then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in New Delhi, Dara said, “Dada, you are the real guru of subcontinent hockey. Whatever we have learnt was only because of you.” The hockey match was a smashing success as the channels of communication were again laid open between the two countries. Even after over three decades, the image of Dhyan Chand had not diminished a bit in the world of hockey.

But, in India, no one found the time for Dhyan Chand. The simple man who had made the country proud was in penury after retirement. Neither the IHF nor the Sports Ministry took a single step to relieve his financial problems. According to his biographer Nikhet Bhushan, close to the end of his life the legend lamented, “When I die, the world will cry but India’s people will not shed a tear for me. I know them.”

Dhyan Chand was a natural gentleman. A genius. An ambassador in the best sense of the term. He was a hermit who lived the life of a chivalrous knight, high on principles, discipline and self-respect. A person who exuded gentleness on and off the field—a sage of a sportsman.

Kolkata-based Mukherji is a former cricket player, coach, selector, talent scout, match referee and writer

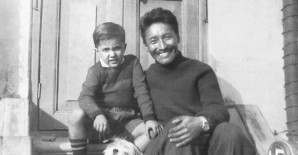

Photo courtesy: Raju Mukherji Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine February 2018

you may also like to read

-

Mental workout

Mukul Sharma tells you how to keep those grey cells ticking Everyone will ultimately lose his or her brain….

-

Helpline

Dr Harshbir Rana answers your queries on personal and social issues related to ageing, elder care and intergenerational relationships ….

-

Off the cuff

Raju Mukherji pays tribute to his first hero, Tenzing Norgay, an exemplary mountaineer Darjeeling, 1955. Dr ‘Pahari’ Guha Mazumdar….

-

Yoga RX

Shameem Akthar shows ways to control debilitating ankle pain through regular practice Ankle pain is so common and prevalent….