Columns

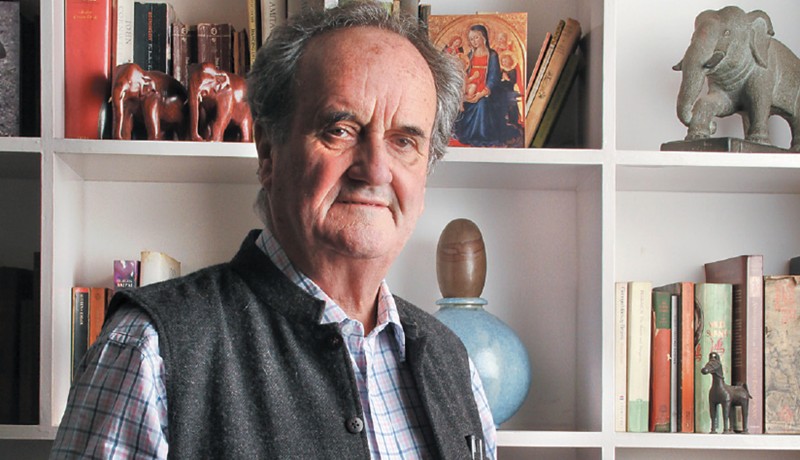

BBC’s Mark Tully, reporting from foreign shores, became the credible voice on India during the dark days of Emergency and press censorship, writes Raj Kanwar.

India was not an alien country for the 30 year-old Mark Tully when he arrived here in 1965 as BBC’s India correspondent. In fact, he was born in Calcutta in 1935 to a British entrepreneur when the British Empire in India was at its pristine glory and Calcutta its numero uno city. It was in Calcutta and at a British boarding school in Darjeeling that a young Mark grew up.

Nevertheless, Mark’s upbringing in India was somewhat sheltered and secluded, very much British-like. For the first five years, there was a stern English nanny who became his matron-mother-mentor all rolled into one. Playing with children of the natives was a strict no-no. He was even forbidden from speaking in Hindi or Bengali since those languages were considered “the language of the servants”. This was to ensure that his upbringing was completely British, devoid of any Indian vestige.

Yet, there was more of India in Mark Tully’s bloodline than England—the native land of his paternal forebears. His maternal forefathers lived in Eastern United Provinces (present-day Uttar Pradesh). His great-great-grandfather was an opium agent and his great-grandfather a trader, though he became a civil servant after 1857. One of his mother’s uncles was also in the Indian Civil Service. Interestingly, his father-in-law was an indigo grower.

As was the practice of British residents in India those days, Mark was sent to England when he turned 10. The focus of the British educational system was to groom students into gentlemen. Mark religiously visited the church. He was good at languages and learnt both Latin and Greek. He also studied theology and history. Mark nurtured a desire to become a priest. But that was not to be. “It so happened that the pub became my favourite rendezvous. I would even entice my fellow students to accompany me. Incidentally, I also enjoyed the company of women. On serious reflection, I decided that the Church was not the right calling for me; the Church authorities too readily concurred,” Mark once told me. What was possibly a loss to the Church was surely a gain for the world of journalism and news broadcasting.

He yearned to be a journalist, yet he could not get an immediate opening. He took up a job with the BBC in London in its human resource division. However, his heart lay in news reporting and he bided his time until he found an opening of sorts in the news section. Finally, his dream was fulfilled when he became the bureau chief in New Delhi. Those 25 years were the most productive and satisfying years of his life. They were the most momentous years in India’s post-Independence history, and he had the privilege of having a bird’s-eye view of all those events. In no time, Mark created a niche as a foreign correspondent and over the following years became the recognisable face and credible voice of the BBC in India. During those heydays, Mark gathered legions of fans all across the country. I was then one of his most diehard fans and admirers. At times, I even envied his immense popularity and dreamt of becoming Mark Tully’s clone. I craved to meet him but our paths never crossed then. In due course, I got deeply involved in my new business that took me not only all across the country but elsewhere in the world. In those hectic travelling schedules, Mark Tully faded into the background.

Meanwhile, his popularity soared, taking him to iconic heights. Those were tumultuous years. Jawaharlal Nehru had died a year before Mark’s arrival in India. Indira Gandhi ruled the roost then. The 1965 war with Pakistan and birth of Bangladesh in 1971 were some of the important events Mark covered. There were also a string of historic tragedies that rocked the country. The Bhopal gas tragedy was the most upsetting. The clamping of Emergency by Indira Gandhi was one of the darkest periods in the annals of Indian parliamentary democracy. The upright BBC journalist did not shy away from calling a spade a spade. Indira, as was her wont, took much umbrage, and there was a move to arrest him. Here is the story in Mark’s own words, “I heard it from Inder Gujral that a man named Mohd Yunus in Indira Gandhi’s darbar wanted to take my trousers down, give me a good beating and arrest me. I had subsequently recorded all this in a book. The provocation was a canard that the BBC had reported the resignation of Jagjivan Ram, which in reality we had not. It was Gujral who thus saved me.”

Mark was then deported to England. However, that did not stop him from reporting on the goings-on in India during that dark period. “The result was that the whole of India tuned in, then and thereafter, to my radio’s broadcasts, ‘The Voice of India’, to hear what they thought was an accurate coverage of events,” Tully later wrote. He once even managed to sneak into India under an assumed name. Eventually, the deportation order was withdrawn.

Mark also roundly criticised Operation Blue Star and the atrocities that followed Army operations. The attack on the Golden Temple had produced a sense of outrage among all sections of the Sikhs. Together with his friend and colleague Satish Jacob, Mark wrote a book on the subject, Amritsar: Mrs Gandhi’s Last Battle.

It was only three years ago that my long-nursed unfulfilled wish came to fruition when Mark Tully and Satish Jacob came to Dehra Dun at the invitation of the Doon Library and Research Centre and Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. The enthusiastic response he received at an interaction with students from several schools was truly amazing. None of those present at the meet were even born during Mark Tully’s reign as the uncrowned king of foreign correspondents, yet Mark received a standing ovation. However, it was that evening at a dinner with select guests that I had the pleasure of having Mark to myself much of the time.

We stood in one corner and talked random stuff, sipping our drinks. He drank beer and I Scotch. “Why do you drink beer at this time as it is generally a daytime drink?”“Oh! I love beer,” he said. “When do you drink Scotch?” I asked, holding my own glass. “I reluctantly take Scotch whenever I run out of beer, but that is very rare,” he said, taking a swig from his mug. And so, the conversation followed.

Mark has spent much of his life in this country. In many ways, he is truly an Indian. All his five siblings were born in Calcutta. His older son Sam is married to Nandita, an Indian banker in London. His younger daughter Emma is married to Peter Kerkar, son of a Swiss mother and Marathi father. And now Mark has become an Overseas Citizen of India. An uninterrupted spell of nearly three decades as a foreign journalist in India must have been something much more than a mere odyssey of rediscovery for the 81 year-old Mark Tully.

The writer is a veteran journalist based in Dehradun

Photo: Harmony Archives Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine September 2016

you may also like to read

-

Mental workout

Mukul Sharma tells you how to keep those grey cells ticking Everyone will ultimately lose his or her brain….

-

Helpline

Dr Harshbir Rana answers your queries on personal and social issues related to ageing, elder care and intergenerational relationships ….

-

Off the cuff

Raju Mukherji pays tribute to his first hero, Tenzing Norgay, an exemplary mountaineer Darjeeling, 1955. Dr ‘Pahari’ Guha Mazumdar….

-

Yoga RX

Shameem Akthar shows ways to control debilitating ankle pain through regular practice Ankle pain is so common and prevalent….