Columns

Shameem Akthar Explores The Link Between Pilates And Yoga.

Not many people, except practitioners of either, know Pilates and yoga are very closely related. Equally few people know that Pilates is actually eponymous with its creator Joseph Pilates. Much of Pilates is actually yoga, with very evolved props and machines.

Joseph Pilates, a German, was interned in England during World War I. He was avidly into fitness, because he was born a sickly child and made himself strong through a well-rounded fitness regimen. During his internment, he taught his physical fitness routine to the others interned along with him. When the great flu swept through England in 1918, his trainees and he escaped its travails. This convinced him he was on the right track. He migrated to the US and set up fitness studios; he became popular largely because of his celebrity clients, many of whom were famous dancers.

The similarity between yoga and Pilates is striking, though there is a lot more attention on muscular awareness and isometric contractions in Pilates. It is dynamic and entirely focused on the physical aspect of healing, unlike yoga which engages the mind and the breath in various related practices like meditation and pranayama (breathing practices). In Pilates, the props help further prod the practitioner into poses and deepen them. Though some basic props are used in yoga too (blocks, belts), they are not extensive. What’s more, Pilates poses have different names that are easy to remember unlike in yoga, which largely features Sanskrit names based on natural objects or creatures they resemble (makarasana/crocodile) or the action of the muscle or action involved (dwipada bhujapidasana/two-legged shoulder-pressing pose).

Those who practise yoga will find Pilates engaging and different because of the approach of the training. But they will also find an affinity. Indeed, it is not improbable to have many serious practitioners of either science borrowing from the other and incorporating a feature that expands their practice further.

YOGIC MOVES

Saw (Pilates) or merudandasana/spinal pose (yoga)

Sit with your legs extended and split wide apart. Ensure the knees do not lift up. Push toes towards your face (flex your feet). Keep your hands out at shoulder level. The back should be straight, hips pushed down, and legs fixed firmly on the mat. Inhale; twisting your torso, exhaling, reach your right hand towards (or ahead, if flexible) the left foot. Inhale; return to the centre and, exhaling, reach your left hand to the right foot (or beyond). Do this dynamically, about 10 times. Points to note: The body leans forward every time the hand extends towards the foot. The other hand extends straight behind. Benefits: This is a terrific combination of poses—a forward bend and a twist. If you lean your face towards the extended leg, it has the benefit of a forward bend: a pelvic squeeze that creates a blood gush to the pelvic region, with a positive effect on the uro-genital system. It tones and keeps the face younger; makes the hips, spine and legs flexible; works out the arms; and improves coordination. The twist tones the spinal nerves, works out the entire back and powers all the organs stacked up along the spine within the torso.

Adi Shankaracharya’s Atma Shatakam

This is a compact delineation of the Vedantic mind, which forms the substratum of all yoga. As much as yoga is of the body, its original intention was to use it to understand the spiritual connection that runs through the whole universe. In these verses, Adi Shankaracharya explains the entire philosophy of Advaita Vedanta (of non-dualism). He is said to have sung this in response to the master Gaudapada’s query as to who he was. To go to the beginning of the story, the teenaged Adi Shankaracharya, who leaves his widowed mother and home in search of self-realisation, wants to become the disciple of Gaudapada who asks him who he is. Shankaracharya, already evolved, explains that he is not the mind, the body, nor the senses, the organs or their systems. He is beyond all these obvious things to which we appear attached. He is that one which runs behind all these things, like a string through pearls. For those who are enraptured by the idea of Advaita—non-dualism—this is an enthralling set of verses.

Available in a song format, all over the Net, it is the most compact definition of the yogic mind, and the quest and purpose behind sadhana. To explain the cosmic principle, more commonly called Brahman, he uses the term Shivoham (I am Shiva principle/I am that one which is Bliss Eternal). The set of slokas are also referred to as Nirvanastakam. Given below is a rough translation. One can read or sing these verses to connect to the idea of cosmic connection and understand the yogic aspiration and mind:

I am not this mind, nor this body. Neither am I the intelligence, nor am I the ego. I am not in the senses, nor in their actions. I am not the breath, nor in its five expressions. I am not in any of the five elements. I am not in the emotions. I am not in the four stages of a human being. I am not bound by the good or bad. Nor in scriptures or spiritual acts or places. I am not the subject or object of pleasure. I am that Eternal Bliss Consciousness.

Shameem Akthar is a Mumbai-based yoga acharya. If you have any queries for her, mail us or email at contact.us@harmonyindia.org. (Please consult your physician before following the advice given here)

Photo: iStock Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine September 2016

you may also like to read

-

Mental workout

Mukul Sharma tells you how to keep those grey cells ticking Everyone will ultimately lose his or her brain….

-

Helpline

Dr Harshbir Rana answers your queries on personal and social issues related to ageing, elder care and intergenerational relationships ….

-

Off the cuff

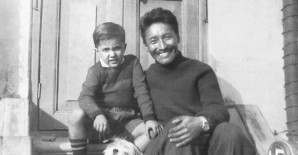

Raju Mukherji pays tribute to his first hero, Tenzing Norgay, an exemplary mountaineer Darjeeling, 1955. Dr ‘Pahari’ Guha Mazumdar….

-

Yoga RX

Shameem Akthar shows ways to control debilitating ankle pain through regular practice Ankle pain is so common and prevalent….