Etcetera

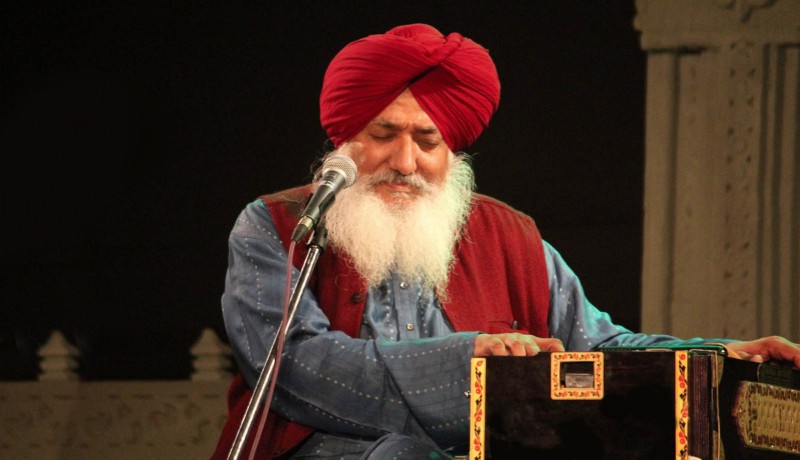

“To perform on the main stage in Zenana Deori at Mehrangarh Fort might induce a cosmic state. The vastness and the openness at this unprecedented height is as if one is performing for the firmament and the stars along with the dancing audience,” expresses versatile musician Madan Gopal Singh as he muses over his recent performance at the World Sacred Spirit Festival in Jodhpur. “This performing space is unlike any other I have seen in my long career as a singer.”

The son of renowned Punjabi poet Harbhajan Singh, Madan Gopal Singh taught literature in an evening college affiliated to the University of Delhi for over 40 years. He started singing as an amateur and went on to establish a quartet ensemble, Chaar Yaar, joining hands with guitarist and banjo player Deepak Castelino, sarod player Pritam Ghosal and multiple percussionist Gurmeet Singh, performing around the world. Though initially the group explored ancient Sufi texts of Baba Farid and Rumi, it started experimenting with songs and poetry of various international cultures across different timelines, ranging from Brecht, Lorca, Tagore and Puran Singh to Hikmet, Hamzatov, Faiz and Nagarjun, creating musical bridges.

For his part, Singh has written scripts for films such as Rasayatra and Name of a River and lyrics for films such as Idiot and Qissa. The 69 year-old has also composed music for largely art-house cinema (Paradise on the River of Hell, Khamosh Pani). In an email interview with Sai Prabha Kamath, he discusses his inspirations and unusual approach to music. Excerpts:

You wear many hats—composer, singer, lyricist, actor, screenwriter, film theorist, editor. Which is the closest to your heart?

I would like to believe I am a good listener of music and a willfully erratic reader of all kinds of books—especially poetry and reflective, philosophical writings of various persuasions.

How do you define the music you create?

Music happened without any conscious training. It happened because of the romance of my youthful enthusiasm to relate to various anti-war moments while I was at university. The subsequent desire to create music was triggered by a sense of profound sadness at the quantum of strife one witnessed in the 1980s and ’90s. One thought that there was an express need to intervene to help protect all that was compassionate and plural in our lived and remembered histories.

Your inspirations?

My initial inspirations were my parents. Also the early morning, whispered scripture recitals by my mother and some of the truly great poetry to which we were exposed to as children in our chaotically multicultural and multilinguistic house. In music, Mallikarjun Mansur, Kumar Gandharva, Tufail Niazi, Salamat Ali Khan, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Mohammed Rafi, S D Burman, Jyotirindra Moitra and many more… too numerous to count.

What were your turning points as a musician?

I started singing as an amateur with well-known painter Manjit Bawa (who used to accompany me on the dholak) as a late-evening pastime to unwind. The community of artists around soon fell in love with the range of music and poetry I had imbibed and we could go on singing for hours together. Other friends, such as Safdar Hashmi, M K Raina, Mani Kaul and Kumar Shaha, took note of our unusual approach to music and the entire project kept growing.

What was the genesis of Chaar Yaar?

Prior to Chaar Yaar, I was singing as Madan Gopal Singh accompanied by my musician friends on various instruments. However, around 15 years ago, I felt the need to underline the inclusive and celebrative nature of our music in an atmosphere where religious and ethnic identities were beginning to tear asunder the very idea of our singular plurality. I decided to step back and give ourselves a group profile. Chaar Yaar, thus, became a definitive gesture of coming together of musicians belonging to four different religions and four different regions.

What is the role of music in society today?

It is a reaffirmation of our oneness in plurality. It is also a resonant way of remembering our archetypal pasts in which compassion, sharing and maintaining the inviolable sanctity of the other is paramount. It is also perhaps the most effective way of renewing ourselves and, thus, protecting our creative spirit from becoming stale and moribund.

What is the response to Sufi music in India?

Sufi music in India has grown in conjunction with the local cultures of India and has hence remained seductively organic and alive. It has avoided falling into the trap of some assumed purity. It has gained huge reach in India as a kind of a ‘patchwork quilt’ rather than ‘wall-to-wall carpeting’. It has been able to cut across multiple culture and ethnic registers and has remained incredibly sensuous and alive.

A moment you cherish….

To sit inside a musical note and persist till its resonance begins to overwhelm my being.

Your best performance?

May happen one day but I have enjoyed too many in India and abroad to single out one.

Photo credit: Mehrangarh Museum Trust March 2019

you may also like to read

-

Cracking the longevity code

Small yet impactful choices can be game-changers, writes Srirekha Pillai At 102, there’s no stopping Chandigarh-based Man Kaur, the world’s….

-

Home, not alone

While a regulatory framework is vital for senior-care facilities, the need of the hour is to develop an ecosystem to….

-

Birthday Girl

Published in a special edition to honour Japanese master storyteller Haruki Murakami’s 70th birthday, Birthday Girl (Penguin; Rs 100; 42….

-

A huge treat for music lovers

Published as the revised and updated second edition, Incomparable Sachin Dev Burman (Blue Pencil; Rs. 599; 470 pages) the authoritative….