Etcetera

Sanskrit and film don’t often go together—whereas film is a medium of communication used to reach the masses, the ancient language of Sanskrit is viewed as the preserve of a privileged few. So when Sanskrit professor Dr G Prabha, 60, combined the two to make an evocative film on Kerala’s Namboothiri Brahmin community, he aimed to take Sanskrit to the common man while shining a light on how socially regressive ancient customs can be.

“Sanskrit will remain self-centered and within a certain community or religion if we only associate it with scripture. But language is universal. To make it relevant, we should move away from classical subjects and start telling contemporary stories,” says Dr Prabha, retired head of the Department of Oriental Languages in Chennai’s Loyola College. His film, Ishti, is one of few Sanskrit feature films ever made, and the only one that ventures away from mythology and biopics. Set in the early 20th century, it revolves around a prominent Namboothiri Brahmin family entrenched in orthodox rituals and regressive practices.

Dr Prabha, who originally hails from Kerala, has also worked as a freelance writer and published several short stories in Malayalam. Inspired by 20th century social reformer V T Bhattathiripad, who led the reforms against the inequality and patriarchal traditions of the Namboothiri Brahmins, he has been mulling over the story of Ishti for 15 years. Owing to their very nature as keepers of Vedic knowledge, the community stubbornly clung to their identity even as change swirled around them. But it was only a matter of time before change seeped into their ranks, with the younger generation rebelling against antiquated traditions. This has been mirrored in Dr Prabha’s 108-minute film.

Ishti has been making the rounds at film festivals since its premiere last year. Pratibha Jain spoke to Dr Prabha after the film was screened at the 150th year celebrations of University College, Thiruvananthapuram, recently. Excerpts from the interview:

What is Ishti?

Ishti is another term for atmanveshan, which means ‘search for the self’.

You are a self-taught filmmaker. How did your journey begin?

I have always been fascinated with film as a medium. This interest was fed by the strong visual communication department in Loyola College, where I taught. I have also attended many film festivals and did a month- long course on film appreciation at the Pune Film Institute after I retired in 2014. I stayed on for a couple of months, watching numerous films and having conversations about filmmaking.

What triggered the story?

The story is inspired by the autobiography of V T Bhattathiripad, a Namboothiri Brahmin and a great reformer of the 1940s. He learnt the Vedas by rote and became a priest, but remained illiterate. When I read about his life, there was mention of a young girl mocking him innocently for not knowing how to read and write. Her laughter triggered something within him and he went on to educate himself. This incident played on my mind often. In Ishti, it is mirrored in the life of the 71 year-old protagonist Ramavikraman’s son Raman [played by Malayalam actor Nedumudi Venu], who reveals to viewers his hidden desire to be literate.

Considering this is your first film, what were the biggest challenges?

I have made two documentary films before, but this is my first feature film. The biggest challenge was completing the shoot in time. We took 17 days, a few days over schedule, even though every little detail, from setup to the frame, was planned at the location in advance. And I had so much more in mind… what I wrote, visualised and wanted. For example, I had a story on the plight of the Namboothiri widows. It would have taken another two weeks to depict their lives and correlate it to the film. I had to compromise because we didn’t have the funds for it. Overall, I am glad it happened the way it did or the film may have become too lengthy.

Tell us about your role as director.

It was my story, my script and my direction. Apart from not finding a producer, some actors were also reluctant because there was no model Sanskrit film, no precedent. Except for Venu etan—he is not only an actor; he is a knowledgeable person, who has done many Sanskrit dramas on stage—they are all newcomers. They mingled well with the language and studied hard as I would explain the meaning of each line.

How does screenwriting differ from writing articles or books?

Ishti was screening in my mind for many years! So I used a cinematographer, Eldho Isaac, who had the time to understand my vision, and thus enrich the frame. I was very specific about what I wanted—to use the visual language to create an atmosphere and convey meaning through silence, as much as I wanted to use the Sanskrit language. The background, symbols, colour, light, materials, props and pictures in the frame needed to import meaning. All this has come from keenly watching films, especially the classics. Even from newspaper photographs, paintings and observing nature. You automatically create your own visual language that is influenced by your experiences. But certain concepts or abstract ideas cannot be visualised. You fill in that gap with language. For example, in Ishti, there is a fire that Ramavikraman must maintain unto his death. But the only way for me to convey this is through dialogue.

What has the response been like so far, from experts as well as viewers?

I am delighted that several film festivals across India have screened Ishti. I took it to Thiruvananthapuram recently. The Sanskrit department of University College screened it one morning and then we spent the afternoon discussing the film. It has been applauded on an academic level, and it has been accepted by ordinary people. It portrays the historical background of Kerala, through a new story, in a new language. However, the film has not gone down well with some people. The Brahmana Kshema Sabha in Muvattupuzha, in Kerala, has filed a case against the CBFC for granting the film a U certificate, and me for showcasing the Namboothiri community in a poor light. I am fully aware that the Namboothiris have evolved since then and many of them have made tremendous contributions to literature and culture. This story is of their past, but such practices survive in some communities. As long as individuals or society continue to suppress women in any form, this story will be relevant.

Are there more Sanskrit films forming in your head?

Always. But first I need to find a daring producer who will take that chance.

Photos courtesy: Medha Creations Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine April 2017

you may also like to read

-

Cracking the longevity code

Small yet impactful choices can be game-changers, writes Srirekha Pillai At 102, there’s no stopping Chandigarh-based Man Kaur, the world’s….

-

Home, not alone

While a regulatory framework is vital for senior-care facilities, the need of the hour is to develop an ecosystem to….

-

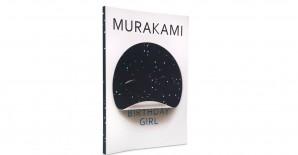

Birthday Girl

Published in a special edition to honour Japanese master storyteller Haruki Murakami’s 70th birthday, Birthday Girl (Penguin; Rs 100; 42….

-

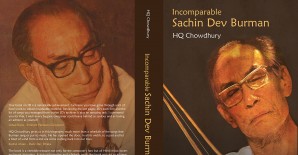

A huge treat for music lovers

Published as the revised and updated second edition, Incomparable Sachin Dev Burman (Blue Pencil; Rs. 599; 470 pages) the authoritative….