Etcetera

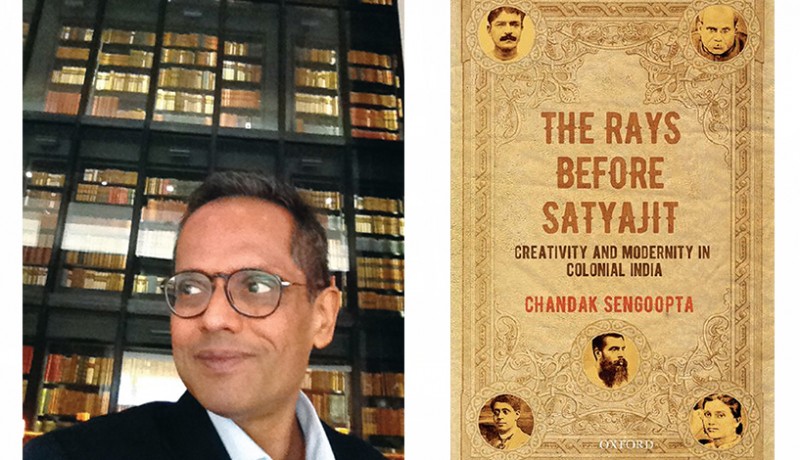

Historian Chandak Sengoopta has a penchant for exploring themes from the past that are not only fascinating but relatively unexplored. The history of European medicine, the history of modern science in India, and the cultural history of modern India are the three domains of research that engage his sensibilities, both as an academic and man of letters. “In all these apparently disparate areas, I focus on the fundamental theme of identity and how sexual, racial and cultural identities are constructed, interpreted and disseminated in different historical contexts,” avers the Calcutta-born writer. Besides numerous research papers, Sengoopta has penned books such as Otto Weininger: Sex, Science, and Self in Imperial Vienna (2000); Imprint of the Raj: How Fingerprinting was Born in Colonial India (2003); The Most Secret Quintessence of Life: Sex, Glands, and Hormones, 1850-1950 (2006); and recently The Rays Before Satyajit: Creativity and Modernity in Colonial India (Oxford University Press; ₹ 995; 418 pages).

The Rays Before Satyajit skilfully draws an extensive canvas of new ideas, discoveries and progressive thinking pivoted on the well-known clan of the Rays. The book also details tribulations and losses borne by Satyajit Ray’s ancestors, men and women of mettle, who contributed significantly towards India’s nationalist politics.

In an exclusive email interview with Suparna-Saraswati Puri, the 57 year-old Professor of History at Birkbeck College, University of London, talks about his literary exercises, with particular focus on his latest title. Excerpts from the interview:

How did The Rays Before Satyajit come about?

For the past few years, I have been researching and writing a biography of Satyajit Ray. The first chapter, about his ancestors and family traditions, kept growing because I found their lives, interests and projects intrinsically fascinating as well as of great, though indirect, relevance to Satyajit’s own work and philosophy. I finally realised the story was too big to be accommodated in a chapter and decided to publish it as a self-standing book. The idea of a book was further reinforced by the lack of any detailed study in English of the pre-Satyajit history of the Ray family.

Was it easy researching the subject?

One potential difficulty of writing on Indian cultural history is the scarcity of sources, especially since I live so far away. Fortunately, however, the British Library in London has a huge collection of Indian material in vernacular languages and has been of enormous help for me. Many of the 19th-century sources I used for The Rays Before Satyajit, for instance, would be very hard to find even in India. We Indians are careless about preserving old books and periodicals and many historical projects have to be shelved simply because one cannot find the sources one would need. I did not have to do that, thanks to the British Library, but despite spending months in Kolkata and in spite of the full cooperation of the Ray family, I could find little archival material such as notebooks, letters, photographs and manuscripts.

How long did the research take?

The research took about three years and was indeed very rewarding. Despite my longstanding interest in 19th-century Indian and Bengali history, there were many new discoveries awaiting me. The history of printing technology, for example, was an eye-opener, as was the history of pre-colonial Hindu scribal communities. But even in areas I was fairly familiar with, I was constantly being surprised by the lacunae in my knowledge. One example would be the historical importance of the Brahmo Samaj in the growth of political nationalism —I was well aware of the religious, social and cultural importance of the Brahmos, but had never adequately appreciated their contributions to 19th-century Indian nationalism.

How much did being a Bengali help in the writing of this book?

Apart from the obvious advantage of having Bengali as my mother tongue, I was helped by the fact that I have long been interested in Satyajit Ray’s historical—as opposed to his purely cinematic—contexts and, therefore, also in his background and ancestry. The research for this book helped me deepen my knowledge of these subjects in countless ways. I was, as I have mentioned earlier, constantly surprised by new facts and details, but the terrain as a whole was not an unfamiliar one.

The book does not have any images to complement the content. Is there any particular reason for this exclusion?

The only images available were of low quality and, moreover, have been reproduced endlessly in other books and articles. Including them in the book would have raised the price of the volume without providing the reader with any material that was remotely unusual. However, including a family chart would have been a good idea. Unfortunately, the thought occurred to me only after the book had been published!

Were you to critique your own writings, what would dominate and why?

Different projects have different shortcomings. Some are owing to factors beyond my control, others stem from my own limitations. In The Rays Before Satyajit, for instance, the main lacuna is the absence of any concrete information on the profits, losses and other aspects of the printing and publishing business founded by Upendrakishore Ray. As all records of the firm had perished long ago—probably after its bankruptcy in the late 1920s—it was impossible to find anything. As for critiquing my own failings in the book, I would probably emphasise the need to have delved more deeply into the voluminous writings of the ‘lesser’ Rays such as Sukhalata Rao, Subinoy Ray and Leela Majumdar.

Which writers fascinated you at different stages?

When in school, I was a massive fan of Arthur Conan Doyle, P G Wodehouse, Agatha Christie and other authors now forgotten but very popular in the 1970s and ’80s. In Bengali, Satyajit Ray was—and is—a big favourite, as was Hemendra Kumar Roy and Sharadindu Bandyopadhyay. I have never been a great reader of the classics but know the works of Tagore tolerably well, and greatly admire Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay. But what has really endured from my youth up to now is my love for the philosophical fiction of the great Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges. Borges’s story Averroes’s Search should be compulsory reading for historians, along with his essay Kafka and His Precursors.

How do you juggle your academic schedule and literary commitments?

For this book, I was very fortunate in having a research grant from the Leverhulme Trust UK, which relieved me of teaching responsibilities for some time. Without it, I would probably still be working on the book!

Have you ever experienced writer’s block?

Writing is always difficult—and slow—for me, but one can always continue with research even on bad writing days.

How do you unwind?

I like to read detective stories, go to the cinema, and sometimes play with my cats.

Do tell us about your immediate family.

My wife, Jane Henderson, and I have no children. We live with our two cats Barney and Bella. Jane has an elder sister in Canada and I have one in Kolkata.

Pic courtesy: Chandak Sengoopta Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine December 2016

you may also like to read

-

Cracking the longevity code

Small yet impactful choices can be game-changers, writes Srirekha Pillai At 102, there’s no stopping Chandigarh-based Man Kaur, the world’s….

-

Home, not alone

While a regulatory framework is vital for senior-care facilities, the need of the hour is to develop an ecosystem to….

-

Birthday Girl

Published in a special edition to honour Japanese master storyteller Haruki Murakami’s 70th birthday, Birthday Girl (Penguin; Rs 100; 42….

-

A huge treat for music lovers

Published as the revised and updated second edition, Incomparable Sachin Dev Burman (Blue Pencil; Rs. 599; 470 pages) the authoritative….