Etcetera

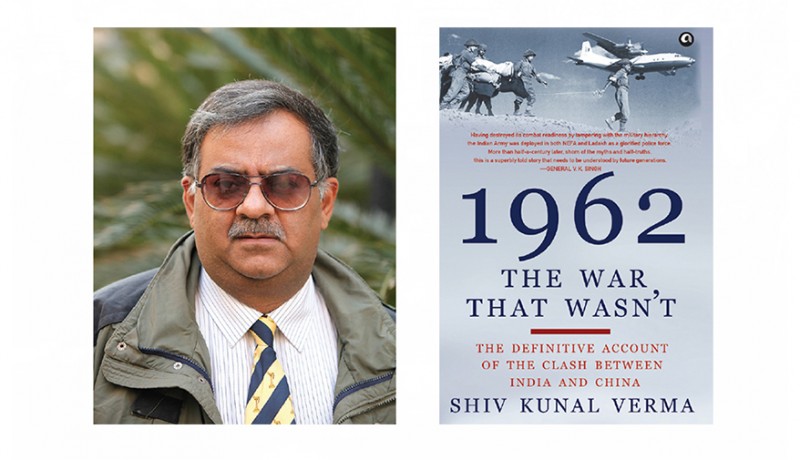

Documentation is Shiv Kunal Verma’s forte. Whether as a filmmaker or defence chronicler, this 56 year-old’s style of storytelling is distinct and dispassionate. “I was born into 2 Rajput,” says Verma, who is considered an authentic voice on military affairs, thanks to over 25 years of engagement as a chronicler with the Indian defence forces. Incidentally, 2 Rajput, his father’s parent battalion, was annihilated in the 1962 War. “The challenge in writing about wars is that everyone has his own version of events,” affirms the writer.

With his informative and straightforward style,Verma has contributed significantly towards literature on conflict. Some well-known titles include Ocean to Sky: India from the Air (2007); The Long Road to Siachen: The Question Why (2012) about “the geopolitical reality that has plagued the subcontinent”; and the recent 1962: The War That Wasn’t (Aleph; ₹ 995; 425 pages). “How do we expect the younger generation to learn unless we unravel what really happened? My book is an attempt to set the record straight,” he says.

In 1992, along with wife Dipti, Verma made a historical documentary film for IAF titled Salt of the Earth. J R D Tata underwrote the entire cost for the film. Other films by the couple include Naval Dimension, Making of a Warrior, The Kargil War and Aakash Yodha about the airborne attack during the 1999 Indo-Pak conflict. After his three years in Ladakh with Tiger Tops Mountain Travel, an environmentally responsible tourism initiative, Verma joined India Today and then worked with Associated Press before directing the Project Tiger television series. At the release of 1962: The War That Wasn’t, organised by Panjab University in association with Chandigarh Literary Society, Suparna-Saraswati Puri interacted with the author. Excerpts from the conversation:

Do writing and filmmaking go hand in hand for you?

At a basic level, storytelling is at the centre of both writing and filmmaking. While in a film, storytelling is visual, in writing one has to use words to paint the same picture.

What were the challenges you faced while writing 1962: The War That Wasn’t?

I wanted to write the book for a variety of reasons, first and foremost of which was the involvement of 2 Rajput, my father’s parent battalion. I was a three month-old baby when my parents crossed the Brahmaputra and then the Digaru on the back of an elephant that belonged to 2 Assam Rifles.

The biggest challenge for me was visiting the terrain where our Army was deployed. Take Ladakh for instance, very few people get to the Karakoram Pass that overlooks Daulat Beg Oldi. The Qara Qash and Galwan River Basin—all at altitudes in excess of 17,000 ft—are areas where even present-day commanders have little or no access. I was fortunate that I got to work with Tiger Tops Mountain Travel as it gave me a very good idea of the terrain. Also, while shooting with the IAF I did some really interesting sorties over the most remote posts. Sitting at the back of an AN32 with your legs literally out of the aircraft, it was something else altogether! No amount of maps and satellite images amount to anything—there is no substitute to actually being there. It’s behind me now so I can afford to talk about it with an air of romanticism, but it’s quite back-breaking.

What kind of research went into the book?

By its very nature, 1962: The War That Wasn’t is a different book. When you are researching history of this nature, it’s like opening a door; you never quite know what you’ll find inside. Invariably, there are a large number of other doors behind the door you have peeked into, so you keep digging, wondering where it all leads to. The truth is somewhere out there. In this case, there were many who had tried to tell their stories but it was all lost in a haze of half-truths and self-exonerating accounts. Eventually, it’s while putting all the pieces together that you get the whole picture.

Do you think family members of martyred soldiers have found closure with your book?

Families, I am not too sure, 1962 was too long ago. But as a country, I sure hope so. The first phase of the 1962 conflict was the build-up, which includes the events after the annexation of Sinkiang and Tibet leading up to the Dalai Lama’s escape into India. This includes the entire period of the 1950s, when prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru for reasons of his own encouraged the Hindi-Chini bhai bhai policy and then repeatedly lied to the Indian people that all was well when it was quite obvious that serious trouble was brewing at the border.

The second phase was the events between 8 September (Dhola incident) and the ceasefire, when incompetent officers played out a charade that let the Indian Army and its men down. These officers—mainly Biji Kaul—played complete havoc with the system, so much so that 4 Division literally scattered “like birds at the first twang of the bow”.

The third phase is what happened after the conflict. To protect the prime minister and his immediate group from having to take the blame for what happened, a web of lies was spun, so much so that even officers and men who were part of the action had no clue what the real situation was. This, to my mind, was perhaps the biggest crime. For half a century we let the country live in the shadow of the ‘nine-foot’ Chinaman, whereas in reality, the only nine-foot factor we needed to come to grips was our own shadow!

Do you think politics and literature can be separated?

The reason why this book has been received so well, despite the story in essence being a chronicle of a defeat, is partly because I have also looked at the civilian side of things simultaneously. We have had some excellent writers after Independence who have contributed greatly to the genre of Indian military history, but I feel these have been mainly Army officers writing after their retirement. Most of these officers—brought up to believe that the Army is and must remain apolitical—document events from a military point of view. In a system where the actual pants are being worn by the civilian leadership, this is akin to telling a story that is truncated and minus the most important element of all: the political and bureaucratic leadership. The fact that I don’t wear a rank on my shoulders gives me a distinct advantage. By the very nature of my style, I am telling or trying to tell the complete picture.

What was of pivotal concern while researching for the book?

Regardless of battalion, personal affiliations were pivotal. It is easy to point fingers at others but extremely difficult to acknowledge the failure of your immediate own. The Kargil War taught me one thing: three men fighting the same battle will give you three different perspectives. It’s important to understand that the ‘I’ factor gets heightened during a conflict where bullets are flying around. To be able to then arrive at what you think actually happened is the key to writing a definitive book. I certainly did not want the book to be an ‘also ran’. I felt we, as a country, owed it to the men who fell in both Ladakh and North East Frontier Agency (NEFA). My book is a posthumous tribute to them.

How do you relax?

Between bouts of feverish writing, I’m generally quite relaxed. I like to take my Labrador Blaise for a walk or go over what has been written with Dipti.

Tell us about your father’s role in the writing of this book?

My dad, who had fought as a captain in the 1962 war, was a major bouncing board for this book and we would talk endlessly about what happened. In fact, I think it was the last book he read before he passed away.

What next?

I’m trying to get the 1965 book going, but at present I am mentally too drained to start writing just like that. I will have to get to the keyboard again—1965 is to be followed by the 1971 war, after which David Davidar, my publisher, wants me to do a fourth volume that covers Siachen, Blue Star, IPKF and the Kargil War. Finally, to complete the series, the last book will be on the 1947-48 J&K operations.

Photo: Dipti Bhalla Verma Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine September 2016

you may also like to read

-

Cracking the longevity code

Small yet impactful choices can be game-changers, writes Srirekha Pillai At 102, there’s no stopping Chandigarh-based Man Kaur, the world’s….

-

Home, not alone

While a regulatory framework is vital for senior-care facilities, the need of the hour is to develop an ecosystem to….

-

Birthday Girl

Published in a special edition to honour Japanese master storyteller Haruki Murakami’s 70th birthday, Birthday Girl (Penguin; Rs 100; 42….

-

A huge treat for music lovers

Published as the revised and updated second edition, Incomparable Sachin Dev Burman (Blue Pencil; Rs. 599; 470 pages) the authoritative….