Etcetera

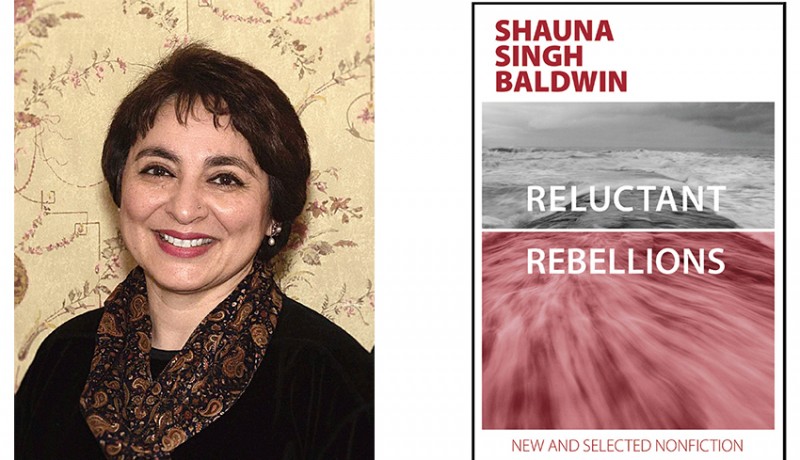

Writing helps share not just ideas and information but, sometimes, even stories. For someone who considers writing “an elitist sport”, poet, playwright, radio producer, restaurateur and author Shauna Singh Baldwin has done remarkably well. The 54 year-old Canadian-American novelist of Indian descent’s multilingual presence (her works have been translated into 14 languages), relatable characters, unique style and expression have earned her an expansive and loyal readership.

Born in Montreal, Baldwin came to India with her family in 1972, when she was only10. After graduating from Delhi University, she left for the US to do an MBA from Marquette University, followed by a master’s in fine arts from the University of British Columbia. At present, she lives in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

A writer who “thinks in English, Urdu, Punjabi and French”, Baldwin took to words because she “needed to make sense of the world” she was experiencing, by describing it. For instance, in her first short-story collection English Lessons and Other Stories, she brought forth her experiences as an ESL (English as a Second Language) teacher. The book won the 1996 Friends of American Writers Award. “Each time I try to write a story only I can write; it must draw on my languages, research skills and cosmopolitan experience to make it unique and meaningful to the reader,” elucidates the playwright of We Are So Different Now, staged last month by the Sawitri Theatre Group in Toronto.

A storyteller who raises questions such as “When is destruction better than creating a new being in the world?” and “What does it mean to name, to withhold your name, to claim, or not to claim, to kill, disown, disagree with or hate what your creation has become?”, she compels engagement. Her repertoire includes What the Body Remembers (2000), winner of the Commonwealth Writer’s Prize for Best Book; The Tiger Claw (2004), a finalist for the Giller Prize; The Selection of Souls, which received the 2012 Council for Wisconsin Writers Fiction Award; and We Are Not in Pakistan (2007), an anthology of short stories, among others. In an exclusive email interview conducted prior to the release of her book, Reluctant Rebellions: New and Selected Nonfiction, published by the Centre for Indo-Canadian Studies, Suparna-Saraswati Puri converses with the author who enjoys reading, biking, walking, swimming, horse-riding and singing.

EXCERPTS FROM THE INTERVIEW:

If not a writer, what would you have been?

When I meet people, I think about their stories. When I did an MBA, I was fascinated by the case studies I came across; I saw them as stories. I guess I was always training to be a writer. I still am.

You once described your writing process as being “fragmented” and “groping” for clarity.

It’s still fragmented and groping for clarity. I see images, hear voices, read and become inspired by a detail here, an insight there, a contrast that only a story might reveal.

As a writer who has commanded different forms of writing, what does your Indian lineage mean to you?

My Indian heritage is a treasure of stories, a submerged worldview that colours my view of power relations. So is my Canadian heritage. I witness it in the US also, where I live. Creativity comes from expressing silenced pain and turning it to beauty, from comprehending the marginalised, from drawing new connections between events and people.

How do you view existing times, embroiled with conflict? Is there a silver lining writers can take recourse to?

Attitudes and fears express themselves differently before the occurrence of actual events. For instance, today in India and the US we hear nationalistic rhetoric and see the worship of flags and regalia. Having written a book set during WWII, I feel we must be careful when we say ‘Never again’. It should not just mean, ‘Never again shall this happen to the Jews in the 1940s in Germany and France.’ Fascist tendencies like purism and fear of the other don’t have any time or location. They lie dormant in each of us. If we succumb to the fear of the other, we could turn Muslims in India and the US into the Jews of the 2000s.

As for how writers can help, I feel we can use satire to laugh at fears, offer simulations in novels to show how conflicts can be resolved. We can discuss and show parallels between the present and the past. Our best historical novels explore the impact of past situations in the hope that readers feel moved to act for positive change. Readers, not writers, can demand and enforce social justice for people beyond and outside the demarcations of caste/tribe/family/nationality/religion. I’m always happy when readers write to tell me they were moved to travel or learn more and take action.

What have been your recent literary inspirations?

I have been revisiting Margaret Macmillan’s Women of the Raj and Paris 1919; Karen Armstrong’s A History of God; and Erich Fromm’s True Believer. For a better understanding of the history of slavery that underlies much of US politics today, I recommend Trinidadian writer Kevin Baldeosingh’s The Ten Incarnations of Adam Avatar. Gauitra Bahadur’s Coolie Woman is essential reading to learn about the period of indenture following slavery. And then to read how indenture was abolished, do read master storyteller Ramachandra Guha’s Gandhi Before India—it should be in every college library!

I have almost finished reading the superbly researched Sophia, by the word-picture artist Anita Anand. Ursula le Guin’s The Dispossessed is still one of my favourites. I return to Octavia Butler’s A Parable of the Sower often to compare the formation of new and ancient religions. Escape by Manjula Padmanabhan was enthralling not only for its story of a journey taking the last girl on the planet to safety and its finely drawn male characters but for its delightful use of Indian food, clothes and ideas in a futurist drama.

How do you view new trends in contemporary Indian writing in English?

As with contemporary writing elsewhere, there is much to love in Indian writing. The arc of art is expansive; we don’t know what will retain significance 50 or 100 years from now. I am glad we now have so many talented Indians writing in English and all other Indian languages. I do wish we had less vanity press and more entrepreneurial publishing, but that too shall come.

What are your views on categorising authors?

Categories are helpful for marketing and for readers to select books. Beyond that, the conversation is all between the book and its reader. The reader will classify the book in the context of his/her history and future.

How different and difficult was your approach while writing an academic book like Reluctant Rebellions: New and Selected Nonfiction?

In contrast with fiction, which requires acting on the page, Reluctant Rebellions is written in my voice. I haven’t written a whole book in my own voice since 1992. The essays span 15 years and some are in the voice of a younger self. While editing, I realised each essay or speech should be considered a response to its time. So I spent a lot of time on the ‘Notes’ section!

Photograph by Centre for Indo-Canadian Studies, University of Fraser Valley Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine November 2016

you may also like to read

-

Cracking the longevity code

Small yet impactful choices can be game-changers, writes Srirekha Pillai At 102, there’s no stopping Chandigarh-based Man Kaur, the world’s….

-

Home, not alone

While a regulatory framework is vital for senior-care facilities, the need of the hour is to develop an ecosystem to….

-

Birthday Girl

Published in a special edition to honour Japanese master storyteller Haruki Murakami’s 70th birthday, Birthday Girl (Penguin; Rs 100; 42….

-

A huge treat for music lovers

Published as the revised and updated second edition, Incomparable Sachin Dev Burman (Blue Pencil; Rs. 599; 470 pages) the authoritative….