People

The force behind India’s right-to-information movement Aruna Roy continues to fight for the ‘other India’. Teena Baruah gets a ringside view of her battle against corruption

Early morning on 5 November, the lawns at India Gate in Delhi resemble a carnival. Streamers blow in abandon — the intense energy of puppeteers and Mangniars (a community of Rajasthani folk singers) performing on mud platforms have as much to do with it as the winter breeze. Potters with mud dripping from their elbows work away at their wheels. There are banners and photographers in colourful scarves holding their cameras up high to get wide-angle shots. Only, instead of their wares, the participants have a social agenda to showcase.

A counterpoint to the colourful ambience, angry voices speak of corruption, rape, and denial of wages. Street theatre performers carry a dummy coffin and folk singers mock nepotism and ‘red-tapism’. A young woman protestor shows another how to make room with her arms as they push through the crowd, which includes representatives of civil society organisations, development workers, social activists, and Panchayat members, debating issues such as governance, laws, ecology, irrigation, food security, integrated medicine and children’s rights.

Helming this unique debate on federalism organised by the Union Government (a prelude to the Fourth International Conference on Federalism at Vigyan Bhavan) are ecologist-activist Dr Vandana Shiva, cardiologist Dr Naresh Trehan, environmental activist Anupam Mishra, water conservationist and Magsaysay Award winner Rajendra Singh, Yogendra Yadav, sociologist and co-director of Centre for the Studies of Developing Societies, and environmental activist Sunita Narain.

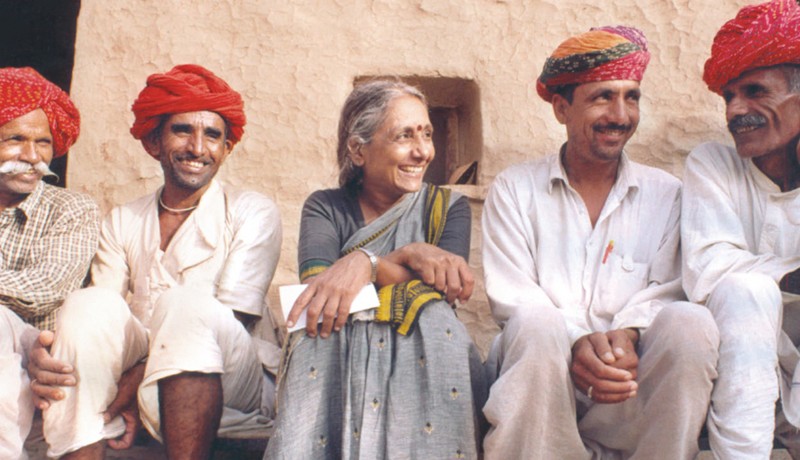

A few yards away, social activist Aruna Roy, 61, stands leaning against a banyan tree. “I am glad the Indian government is participating in change,” she says. Then looking around her, she breaks into a sudden, unexpected smile. “I cannot live in compartments. While my mind is at work for the rights of our villagers, I am also listening to this fabulous music, watching the potter at work.” Just as suddenly, the smile is gone. “The order of the world is a façade and behind that the real world is disintegrating into chaos.”

Roy, propeller of the Rajasthan Right to Information Bill that paved the way for the Right to Information Act in 2005, continues to raise awareness over the issue of file notings — official remarks that play a pivotal role in the future of various projects. Initially, the government wanted to amend the Right to Information Act by excluding file notings from public view but later, in November 2006, capitulated owing to pressure from Roy. (Areas like defense, security, personnel and intelligence are still cordoned from public scrutiny.) Roy continues to keep the issue alive, refusing to be complacent about it — that’s a characteristic she feels is reserved for bureaucrats, not activists.

Roy began her career as a junior officer in Indian Administrative Service in 1968. She was always uncomfortable with occupational hierarchy. Also, she found herself making decisions without adequate information. Frustration mounted when she realised she couldn’t change the system — or the fate of poverty-stricken villages. What also worked against her was her temper, which reveals itself when you dig into her private space. But we were forewarned. Roy, in fact, first got cross with her world while travelling to Indraprastha College in Delhi on public buses, dealing with sexual harassment en route. Her anger didn’t always come in handy when she fought against gender inequality in public spaces, her own larger family and in the IAS.

So, after seven years of government service, she resigned and joined the Social Work and Research Centre (SWRC), an NGO better known as Barefoot College, led by her husband Sanjit ‘Bunker’ Roy. This world-renowned experiment is engaged in rural development projects in Tilonia, a village 100 km from Jaipur, Rajasthan.

“I didn’t know what a village was,” recalls Roy, whose experience at SWRC convinced her that poor people needed to be agents of their own economic and social improvement. On 1 May 1990, villagers from Rajasthan, steered by Nikhil Dey and Shankar Singh, approached Roy to join in their Right to Information movement, sparked in the late-1980s by villagers’ anger over being denied their wages. They alleged manipulation of government records that claimed they hadn’t worked at all. “They felt that tabling government records and scrutinising them publicly would help solve the problem,” recalls Roy, who later, with Dey and Singh, founded Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS) to empower these villagers. In the process, she shifted her official base to Devdungri, a village on National Highway 8, near Bhim in central Rajasthan. Symbolic of the other, darker side of prospering India, Devdungri has become Roy’s second home.

From here, Roy began staging hunger strikes, sit-ins and rallies, slowly moving to other villages across Rajasthan. Shankar Singh, a resident of Tilonia and ‘communication in-charge’ at Barefoot College, created an ensemble of song, dance, drama and puppetry to bring home the message about issues like education, health and politics. Soon, the crowds at her rallies swelled.

“Her speeches, delivered in chaste Hindi laced with Rajasthani and a hint of a Tamil accent are as unpretentious as she is,” says Yogendra Yadav. “Aruna Di almost never uses the singular ‘I’; every reference includes her and her colleagues at MKSS. That’s probably the reason she has retained and gained comrades. In that sense, she represents the legacy of the best of our national movements.”

Finally, the government launched an official enquiry to investigate denial of wages to villagers. Its report revealed that a bogus company comprising government employees regularly received illegal payments for work that had never been done.

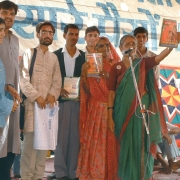

“The movement, however, took shape only in 1994 when a villager from Kot Kirana in Rajasthan’s Pali district complained of not receiving his daily wages. We at MKSS promised to fight his case only if he demanded access to records for the period he worked on the project. As the government was determined to stifle our efforts, we organised Jan Sunwai [public hearing] platforms at which records of development projects were exposed to the scrutiny of intended beneficiaries,” says Roy, disclaiming popular belief that she was the mastermind of the campaign to pass the Rajasthan Right to Information Bill, which paved way for the Right to Information Act in 2005.

“In fact, the people educated us,” she adds. “And Jan Sunwai meetings between December 1994 and April 1995 proved the potential of the right to know.” Shocking revelations followed. Of toilets, schools, health centres recorded as paid for but never constructed; of improvements of wells and roads that remained unimproved; of famine and drought relief never rendered. Such revelations embarrassed culpable officials and led to apologies and investigations, even return of stolen funds.

In 2000, Roy won the Ramon Magasaysay Award for “community leadership for empowering villagers to claim what is rightfully theirs by exercising people’s right to information”. “Being an administrator she brings into activism a disciplined approach,” says Mrinal Pande, editor-in-chief of Hindi newspaper Hindustan. The Magsaysay earned Roy support from Pande and other journalists, intellectuals and reformers who joined in the right-to-information movement to give it a national dimension.

As a result, the Right to Information Act was born in October 2005 — and propelled Roy’s name into the headlines. “However, Aruna hasn’t been corrupted by success,” insists B G Verghese, columnist and senior fellow at Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi. “She has built a group of activists to take the cause forward. This is rare in times when activists are using their causes to leverage their position.”

A battle was won, but it took Roy a long time to fight her own demons. “I was unaccustomed to community living,” she remembers. “Also, after years in IAS, I had to change from talking to listening.” The mud hut she shared with her colleagues Nikhil Dey and Shankar Singh had two rooms, both about 16 x 4 ft. White ants ate away many of her books and papers. This room is still her office in Devdungri. There is still no electricity and the only luxury is a toilet connected to a septic tank. “I had to be toilet trained once more to fit into village life,” she jokes.

The smile and wit are rarely seen by outsiders today. Roy’s friend and IAS batch mate Madhu Bhaduri recalls their days at the IAS training academy in Mussoorie, when “being with Aruna meant fun and laughter”. “She still has a sense of humour, but she doesn’t talk the way she used to.” Perhaps because Roy’s life is consumed by anger. Many things make her angry — like hype about 8 per cent growth in economy while the minimum wage of a worker in Rajasthan, including hers, remains Rs 73 a day; and inequality in development in Devdungri. She is also angry about Nandigram and questions the power of Parliament to decide what people should do with their natural resources. “Inequality and lack of development are pushing people to extremism,” she says. “Nobody wants to stay in a state of violence. But if my alternative is death, either through hunger or being beaten by police, I’d die fighting. I will kill and get killed.”

“For Aruna, her life and work merge seamlessly,” says actor Nandita Das who considers Roy her mentor. “Since my college days when I was involved in grassroots projects in Tilonia, I have been with her on dharna many times. Most people in the field have become cynical and angry fighting the system. But Aruna has never let the anger consume her. She has channelled her angst constructively.”

Roy is also angry about religion in India — Ayodhya made her realise that faith is not a private space. “Have you seen the made-in-China rakhi threads and Ganesha idols? Is that the India we dreamt of?” On being quizzed, she relents, “I don’t believe in established religion. But I celebrate all festivals with my people in Devdungri. That way I’ll never be fundamentalist.”

However, with time Devdungri is becoming a small detail of a larger picture. Her friend, activist Shekhar Singh, 57, feels Roy’s iconic image has pushed her to be part of various movements and kept her away. “She regrets it as Devdungri is where she tests her ideas,” he says. She agrees, saying, “Always being on the road is the biggest price I have paid for being an activist. For me ‘bliss’ is to sleep on the same bed and not move for three days.” Roy travels for about 20 days in a month, but always returns to Devdungri.

That’s also when she steals some time with husband Bunker Roy in Tilonia. “Though we haven’t worked together for years, it’s a good marriage because in some ways it is not a marriage,” she says. “We give each other space and it’s an equal relationship.” The two married simply in 1970. They decided not to have children to tie them down, and not to be financially dependent on each other. Roy has never worn a symbol of marriage, “No kara, sindoor, or the dog tags we wear in the South called taali.” She is unpopular among her husband’s family for speaking against dowry and ostentatious weddings but it doesn’t bother her anymore. “Greying has cushioned me against criticism,” she says. “I’ve learnt to live with it.”

Their home in Tilonia, she says, has the same bohemian character of her childhood home in Delhi. “It’s an open house. You can have your own opinion and be emotional about what you believe,” says Roy, recalling dinnertime punctuated by lively discussions. “My mother, a homemaker with a broad outlook to life, used to joke about hanging a sign outside saying, ‘If you don’t argue, don’t enter’.”

In Tilonia she enjoys luxuries she doesn’t get in Devdungri: a computer, bedroom, books and music system. “Bunker and I listen to music together, in the open. For me, music is a religious experience.” Music is a habit she picked up during her time at Kalakshetra, an arts academy in Adayar (Chennai), where she learnt Bharatanatyam, painting and Carnatic music under the guidance of noted dancer Rukmani Devi Arundale. But she refuses to tune in to a Walkman or iPod, as her ear is usually glued to the phone, which rings incessantly.

People call her all the time to request her for lectures, interviews, sound bytes on politics and democracy. Roy handles all calls at an unhurried pace, accepting some, refusing many. “With age, I have become more careful about my body,” she says. “I used to treat it like a slave. Now, when I am tired it says ‘no’.” Of late, overexertion causes nausea, body pain and distress and she takes days to recover. “Sometimes, I switch off my mobile for two hours. If that doesn’t help, I do Vipassana, meditating for 10 hours at a stretch. But I’ll be damned if I rest in peace till there’s corruption around me, though I know it will go on beyond my life.”

Featured in Harmony – Celebrate Age Magazine December 2007

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….