People

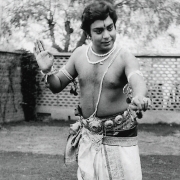

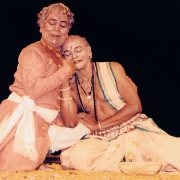

Birju Maharaj’s recent biography is testimony to a life dedicated to the arts. In conversation with Sudha G Tilak, India’s foremost exponent of Kathak elaborates upon how his dance form has evolved through the ages

It is morning and Pandit Birju Maharaj is at prayer. Fresh from his bath, he practises a routine his father and grandfather had probably followed. Dotting the silver idols and images of gods, predominantly Krishna, and those of his forefathers, with fresh sandal paste, he flips open a silk pouch to take his prayer books out.

We are at a Delhi neighbourhood where festivity is in the air before Diwali. Maharaj’s home is festooned with flowers and clay diya and platters of milk sweets and hot tea are served to visiting students, young and old, who troop in to touch his feet and seek his blessings on the auspicious occasion.

If you didn’t know him, he’d be yet another elderly, pious Brahmin from Uttar Pradesh. But the years fall off his face when his eyes flash, lips part and hands move up elegantly to hold a pose. His shoulders flex and his chest puffs and he holds a posture of shringara so perfect he could be a playful young dancer. At 77, he danced a duet with Madhuri Dixit on Jhalak Dikhlaa Jaa, a dance show on TV, enviably agile for his age. And now, he is working to perfect her moves on her forthcoming film, Dedh Ishqiya.

This relentless pursuit of his craft is central to The Master Through My Eyes, a recently released biography of the maestro’s life and times by his eminent shishya Saswati Sen. And it has indeed been an extraordinary journey. The youngest person to receive a Sangeet Natak Akademi Award at the age of 27, Padma Vibhushan Birju Maharaj insists that it is individual devotion that elevates a performance into sublime art. Excerpts from an exclusive interview:

You have been dancing almost all your life. Can you recall the first performance you ever watched?

I was awake to dancing around me at home since I was four years old. My father, Achchan Maharaj, and uncles all danced. They were of the Lucknow gharana. My great grandfather was associated with the court in the royal family of Lucknow. One memory or image I can recall clearly is that of one Janmashtami. The family had a mehfil almost every other day and this was a special occasion. There was a gathering of about a hundred people. The deity was dressed and decorated in silks and flowers. There were flames from the lamps; fruits and sugar lumps were on platters. At a little space ahead, my uncles [Shambhu and Lachhu Maharaj] were dancing, the musicians sat nearby playing and the crowd sat on the floor watching. I ran to the large kitchen where my mother was cooking before huge stoves and told her I wanted to dance too. She said my time would come and thrust a khullar of my favourite malai rabri in my hand that I licked to the last.

You are a self-taught artist. How did that learning happen?

I’d say it was because of the atmosphere at home. At any time, there were students at home and practice would be on. There was music all through; I found myself fiddling with the sitar and learning the tabla. And I was attracted to the music from the harmonium as a child. Tal and sur [rhythm and melody] are part of nature and humans imbibe the music. From my father I understood emotion and devotion in dancing, from my uncles the art of gestures in dance and the power of expression.

What about making music? You have some 100 compositions of your own, many set to dance too.

For me, rhythm is in the heart. The heart’s beat is the first tal for a human being who is aware of this. The child learns the beauty of emotions just after this. Eyes round in joy, her mother plays with him, her expressions of joy, pride, anger, tears, shape the child’s bhawana. The child’s first steps are his dance movements. My earliest and most prolific compositions have been on Krishna owing to this intuitive relationship with the body, devotion to Krishna and the beauty of music. Dance is chitra katha. For a rounded performer, all these aspects are vital to honing one’s art.

Do you think you also had the advantage of being male as you were allowed to pursue dance?

It was a sign of the times. Kathak enjoyed royal patronage and from the durbar it shifted to the proscenium after decades. I was a male dancer and yet my dance was, in the beginning, my livelihood too. After Independence, times changed, stigmas lifted, and there was patronage from the government, especially in Delhi, with the founding of cultural institutions like Sangeet Bharti Akademi, Bhartiya Kala Kendra and Sangeet Natak Akademi, among others. With education, women too emerged from domestic circles and women from all classes took to the performing arts. Today, Saswati Sen is my esteemed student and a teacher in her own right and many of my bright students have been female.

How difficult were the times you came to Delhi with your widowed mother from Lucknow?

My father died when I was nine and I left school. All I knew was that I wanted to pursue dance and my mother was supportive. There were days we had no food and it was a struggle to find spaces to perform. Despite offers from films, I was not too keen. Art historian Kapila Vatsayan was a huge support. Thanks to her, I started teaching dance at Sangeet Bharti in New Delhi by 14 and subsequently at Bharatiya Kala Kendra and later as the head of the department at Kathak Kendra. But I’d seen hard times and I had a large family of children, nephews and nieces to feed and take care of. With no guru, no family savings and a large responsibility, I think a strong mother and my own zest for dance helped me. At the worst of times, my dance and music would elevate me from terrible reality.

How did your art evolve? You have been prolific in composing, shifting from the solo to the ballet formats, introducing a unique style that is dramatic with emphasis on not just speed and superficial beauty but abhinaya and shringara.

Once the fear of survival was removed, I was able to dedicate myself to my dance with greater freedom. My compositions are those that have sprung from nature. From the rustling leaves that makes me imagine a naughty Krishna swinging from treetops to the sparkling river where he defeated the wicked Kaliya, my music and ballets bring nature and mythology and divinity together. Emotions are what we are all about and if dance cannot reflect it and stick just to its grammar and form it will remain soulless. Hence, Kathak for me brings all these aspects into a sublime performance. My language has changed in the past 30 years. My art evolved towards spirituality and devotion that goes beyond the performer’s ego for appreciation and superficial beauty.

Your choreography is marked not just by fleeting footwork but a high emotional quotient and dramatic pauses during the dance. What does the pause bring to your performances?

Often when I am asked about this, I joke that I am holding a pose for the photographer! However, the drama of silence adds to the drama of movement. If a performer were to dance non-stop without a pause before embarking on another dance movement or change in emotion, it would fall flat. We have to catch our breath to release it. The power of silence and the power of halting in your tracks before beginning anew even in the wink of an eye add a new dimension. It is the energy of creating space, shoonya, silence. The tal or rhythmic beat too needs a break before beating on. It sets the mood, space and time and adds colour to the performance.

Classical dances from all regions have been constantly evolving through the ages. Fusion, modern, contemporary, avant-garde and other labels have been added to the sub-genres of dance. Have you not been interested in experimenting with Kathak?

Tradition is the large mother tree. It can grow a variety of branches but the roots remain constant. Similarly, fusion for fusion’s sake will remain fake and will be rejected. Dance and music should reflect true feeling. And art and life move in circles; what was old returns renewed and so on. Despite my large body of work on the classics of Kalidasa, Surdas, the Ramayana and so on, my works on Mirza Ghalib’s poetry using abstract themes of life and feelings, the love legend of Roopmati and Baz Bahadur from Mandu, Laya Parikrama, and the Samachar Darpan, the first offbeat work I created on the morning rituals of a newspaper in a household in Kathak were all equally well-received as my traditional ballets.

You have been choreographing for Indian cinema. Your most famous was Satyajit Ray’s Shatranj Ke Khiladi. How did that come about?

My great grandfather had danced in Wajid Ali Shah’s court. Perhaps that piece of news had reached Ray. His brief to me was that my dance should bring sukoon [peace] to the Nawab’s face. My choreography included recreating Lucknow’s images and culture through the composition. I composed for movies after many years when I worked with Madhuri Dixit in Dil To Pagal Hai; later, I was able to work with each emotion and gesture in Devdas. Recently, I spent a lovely week in Lucknow’s old mansions working with her in the forthcoming Dedh Ishqiya. It was an altogether unique experience when I worked with Kamal Hassan in Vishwaroopam. He sat down and watched me work with the artists and then I realised he was observing my mannerisms for his role of a Kathak teacher. He’s a dear friend now and even came home to play with my granddaughter.

We live in violent times. What is the role of art in bringing beauty and peace into our lives?

As an artist I always remain moved by human affection. At the peak of the anti-Hindi agitation, I was invited in the 1960s to perform to a university student audience in Hyderabad. Even as the mood was hostile outside, as the music began to play and my dance began, I found the agitating students shuffle in to watch the play of Krishna’s leela. Human kindness is expressed aesthetically through any form of nuanced art. And dance is a fluid art form involving the body that makes it come together beautifully.

What will you leave behind as your legacy?

While I can still dance at my age and am choreographing a dance movement or composing a tune in my head at every moment, I realise my dance will live beyond me when I catch a personal gesture or dance move in my grandchildren’s or students’ performances. The Kalashram that I am struggling to get going will hopefully be an institution for dance, music and the allied arts associated with the beautiful dance of Kathak. My art will live on through my students beyond my times.

Will your children also be a part of that legacy?

My eldest daughter Kavita was good at dancing, but domesticity took her away. My second daughter Anita has taken up painting and sculpture. However, my sons Jai Kishan and Deepak and daughter Mamata and my granddaughters are keeping the tradition alive. I watch them dance and in the odd expression or unselfconscious gesture they make, I know my style has seeped into them.

Could you share your secret to active ageing?

Ageing gracefully is a gift we must all seek to receive. At every stage, life is beautiful and if we can accept it in a positive way, things become easier. Music and dance keep me going. Dance is my therapy, my joy. Kathak is the best health tip I offer myself every single day and it keeps my energy levels up and my mind active with composing or creating a piece of dance or music. An active mind helps an active body well into old age.

Photos: Avinash Pasricha Archival images courtesy: The Master Through My Eyes Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine December 2013

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….