People

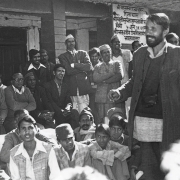

Raj Kanwar meets veteran environmentalist and social activist Chandi Prasad Bhatt, a leading force behind the Chipko Andolan, a movement that brought about ecological awakening among the people of the mountains

It is remarkable for someone born into a family of priests in Gopeshwar—a small village in the backwaters of the Garhwal Himalaya with barely 600 residents—with hardly any education to have become an internationally acclaimed environmentalist and social activist. Chandi Prasad Bhatt’s fame does not rest on any research or academic achievement. Rather, his contribution essentially lies in bringing about awareness and awakening among the people of the hills about the imperative of preserving their environment and ecology.

Renowned for playing a vital role in Chipko Andolan, a forest conservation movement that began in the 1970s, he was instrumental in empowering the aam aadmi and aam aurat in asserting their traditional rights. As Dr B K Joshi, founder-director of the Doon Library & Research Centre and former vice-chancellor of Kumaon University told me, “For Bhatt, environment is not just an abstract concept to be talked and bandied about in seminar halls and drawing rooms but a living reality, inextricably bound with the daily life and struggles of the ordinary hill folk in the rural areas of Uttarakhand and other Himalayan states. He is truly a man dedicated to the Himalaya and preservation of its ecology and environment.”

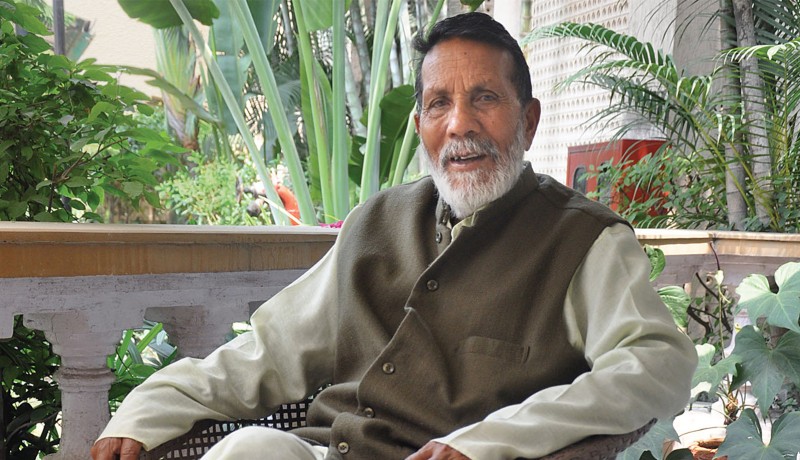

It truly was an honour—and a tad daunting—to meet such a man! As I saw Bhatt enter the lobby of Dehra Dun’s Hotel Madhuban for our luncheon appointment, I stood up to greet him. He doesn’t look 83; attired in loose khadi kurta-pyjama and greyish brown Nehru jacket, the tall, handsome Bhatt, sporting black hair and a grey beard, walked with an easy gait. No handshakes—he greeted me with folded hands and a traditional namaste; the 90-minute interview that followed was more like an informal chat. At my bidding, he began to narrate the story of his life.

Bhatt’s journey began humbly in Gopeshwar; he was just about two years old and his sister a year older when their father died, leaving the two young children and their mother to fend for themselves. Barring some income from a cow, farming, rent from an ancestral cottage and help from an elderly kin, there was no other source of livelihood. “I did my schooling in the nearby Rudraprayag and Gopeshwar towns. However, I opted not to pursue my college education in far-away Dehradun as our income was not large enough to support it. Instead, I taught Hindi and geometry for a year at a high school in Gopeshwar to contribute my mite to the family kitty. Those were the difficult days,” he recalls. He got married in 1955 and that further increased his responsibility. “To meet our living expenses, I took up a job as a booking clerk with the Garhwal Motor Owners’ Union [GMOU] that operated a network of bus services in the region.” The job brought him in touch with hundreds of tourists from various parts of the country. And it opened his eyes—he realised there was more to life than merely earning a livelihood. It was a true discovery for him.

The year 1956 was a turning point in Bhatt’s life when Praja Socialist and Sarvodaya—the Gandhian ideal of ‘progress for all’—leader Jayaprakash Narayan with wife Prabhavati visited the area on their way to Badrinath. “I instantly fell under his charismatic spell,” he remembers. “I also happened to meet a young Sarvodaya leader, Man Singh Rawat, whose views and sincerity tugged at my heartstrings. I took leave of absence from GMOU and joined Rawat on his tour of several villages.”

At the end of that tour, Bhatt became a diehard Sarvodaya adherent and Rawat, his mentor. “By then I had become obsessed with Vinoba Bhave and his Sarvodaya movement. Bhave was to tour Jammu and Kashmir for a fortnight in 1959 and I joined his entourage. It was the experience of a lifetime and I felt spiritually rejuvenated. Then, in response to a fervent appeal by Jayaprakash Narayan for active volunteers in 1960, I made my ‘Jeevan Daan’ to the Sarvodaya movement.” It was a life-changing decision as ‘Jeevan Daan’ turned one into a fulltime, lifelong dedicated volunteer to work for the welfare of fellow human beings. However, both his mother and wife were fully supportive of his decision. “Whatever little income then came from our sundry sources was enough for our sustenance,” he says. “After that, my life no longer remained my own. I also needed to cut my umbilical cord with the past, so I put in my papers with GMOU, and plunged headlong into what was to become my mission for the rest of my life.”

Eager to put into practice the Sarvodaya ideology, Bhatt needed a new entity and platform to carry forward his mission. In 1964, together with a group of dedicated friends, he founded the Dasholi Gram Swarajya Mandal (DGSM), a society for village self-rule. At the time, villages in Garhwal were devoid of meaningful economic activity and lacked employment opportunities, impelling most young people to migrate to the plains. Old parents were dependent on money orders from their sons every month; in fact, newspaper columns had dubbed it the “money order economy”. The women tilled the field, shepherded cattle, gathered wood for fuel, fetched water from long distances and, last but not least, looked after the children. It was, to say the least, a tough life. Bhatt’s DGSM and its message of self-reliance gave them a ray of hope and they supported it enthusiastically. Little wonder then, that they stood at the vanguard of subsequent movements.

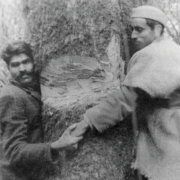

Among other activities, the DGSM organised camps to impart training in village industries, agriculture, horticulture, animal husbandry and harvesting of forest produce. It also held camps in villages in the Alaknanda River’s catchment area with a view to educating women and the youth on the importance of protecting forest wealth and conserving the environment. The first of the tree plantation camps was organised in 1974 by the villagers themselves at Papariyana. Following this, a three-day camp was organised in Pangarbasa forest block to underscore the perils of environmental degradation.

In July 1970, a massive flood of the Alaknanda River had utterly devastated Chamoli district. This, in a way, became the prologue to the Chipko Andolan or Chipko Movement, which was, in years to come, to spread across the Garhwal hills and lay the foundation for community participation in managing natural resources. The impact of the flood was felt right up to Haridwar where the Upper Ganga Canal was completely choked with debris. While the officials called the floods a ‘natural calamity’, those affected soon wised up to the fact that the floods were manmade.

In April 1973, Bhatt brought about a mass awakening in the Garhwal region against the indiscriminate felling of trees when he led a group of villagers in preventing the contractor of an Allahabad-based sports goods manufacturer from felling 14 ash trees. The felling of the trees in large numbers was also part of the government’s policy of auctioning forests for commercial exploitation. Customarily, whole blocks of forests used to be auctioned to private contractors, euphemistically called forest lessees. This custom had begun near the end of the 18th century when the British Indian government auctioned specified trees in a forest block to earn revenue and meet its growing requirement for sleepers for railway tracks.

Initiated and spearheaded by DGSM, a non-violent protest was held in Mandal village, emulating the Gandhian method of Satyagraha. Women and men came out in hundreds to participate by hugging the trees, preventing them from being axed—the Chipko Andolan was born. The same year, in December, the villagers stopped the contractor from felling trees in another area. With this unusually revolutionary yet non-violent stratagem, the movement spread quickly. Gaura Devi, a woman pioneer, led another large protest by women in Reni village in Joshimath block of Chamoli district on 25 March 1974. There were several such instances all over the Garhwal and Kumaon divisions.

These developments were serious enough to jolt the government from its slumber. To placate the agitators, the state government appointed a fact-finding committee under the chairmanship of Dr Virendra Kumar, a Delhi botanist and authority on the Himalayan ecosystem. Besides Bhatt, the local MLA and the block pramukh were also members. In its report, the committee accepted the arguments of the Chipko activists about the causes leading up to the denudation of the terrain. It accordingly recommended that no felling of trees for commercial purposes be allowed in the 1,200-sq-km area of the Alaknanda basin.

This is considered one of the biggest achievements of the movement. Further, on 25 November 1974, the state government constituted the Uttar Pradesh Forest Corporation to undertake scientific exploitation and more effective conservation of forests. This meant that forests would no longer be auctioned to private contractors. Other positive outcomes included a Forest Protection Act, which came into force in 1980; a 50 per cent reservation for women in forest panchayats; and the involvement of DGSM activists in decision-making on tree felling.

“Development ideas such as the protection of environment, the traditional usufruct rights of indigenous people, encouraging participation by women and Dalit families in the decision-making processes and using indigenous knowledge in promoting self-reliance have all been successfully executed by Bhatt’s Dasholi Gram Swarajya Mandal,” points out Dr Ravi Chopra, managing trustee of the Himalayan Foundation in New Delhi and former director of the Peoples’ Science Institute, Dehradun. “The fact that this revolutionary change was brought about at the initiative of the grassroots people with little or no formal education, funds or other help from the outside world makes the achievement truly exemplary.”

Despite the many international and national accolades such as The Raman Magsaysay Award (1982), Padma Shri (1986), Padma Bhushan (2005) and Gandhi Peace Prize (2013) that have come his way for this achievement, Bhatt retains his self-effacing demeanour even today. Fifteen years since he handed over the formal reins of DGSM to his younger comrades and disassociated himself from its day-to-day functioning, he remains actively involved in its activities and regularly participates in the forestry and environment-related camps it organises. An active participant in seminars and conferences on Himalaya-centric and environmental-related subjects all over the country, Bhatt is currently writing his memoirs. “Bhatt is perhaps the only grassroots environmentalist who actually practices what he preaches,” says Avdhash Kaushal, chairman, Rural Litigation & Entitlement Kendra, Dehradun. “He has stuck to his roots and did not move to greener pastures like most of his ilk. Today, he stands head and shoulders above all of them.”

Indeed, Bhatt continues to live in his native Gopeshwar with his wife. “Gopeshwar has been both my janmabhoomi and karmabhoomi,” he says. “My whole being is deeply rooted in its soil.” With his five children (three sons and two daughters) well-educated and settled, he looks forward to the summer vacations when his children and the grandchildren come visiting. “It is now my earnest ambition to spend the rest of my life in making sure that the Himalaya’s environment is not only preserved but further enriched for the benefit of our future generations.”

THE FOREST FACTSHEET

THE INDIAN HIMALAYA

- The youngest mountain chain on the planet, believed to be still evolving

- Major supplier of timber, fibre, oil, spices, organic manure, hydropower, etc

- A storehouse of glaciers, providing perennial river systems for settlements, agriculture and industries

Source: Forest Cover in Indian Himalayan States – An Overview; Satya Prakash Negi; Forest Survey of India

INDIA

- Along with Brazil and the US, India is one of the 10 most forest-rich countries, mainly because of the Himalaya

- The Western Ghats and Eastern Himalaya are among the 32 biodiversity hotspots on earth

- According to the India State of Forest Report 2015, forests cover 21.34 per cent of India’s total geographical area

- According to satellite data analysis and the Food and Agriculture Organisation, India is the third fastest nation in the world in increasing forest cover, adding over 4 million hectare between 1990 and 2010, a 7 per cent increase

Photo: Vinay Santosh Kumar Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine June 2017

AGRICULTURE

WILDLIFE

WATER

WASTE MANAGEMENT

ENERGY

SUSTAINABILITY

EXCLUSIVE COLUMN

EXCLUSIVE COLUMN

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….