People

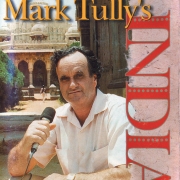

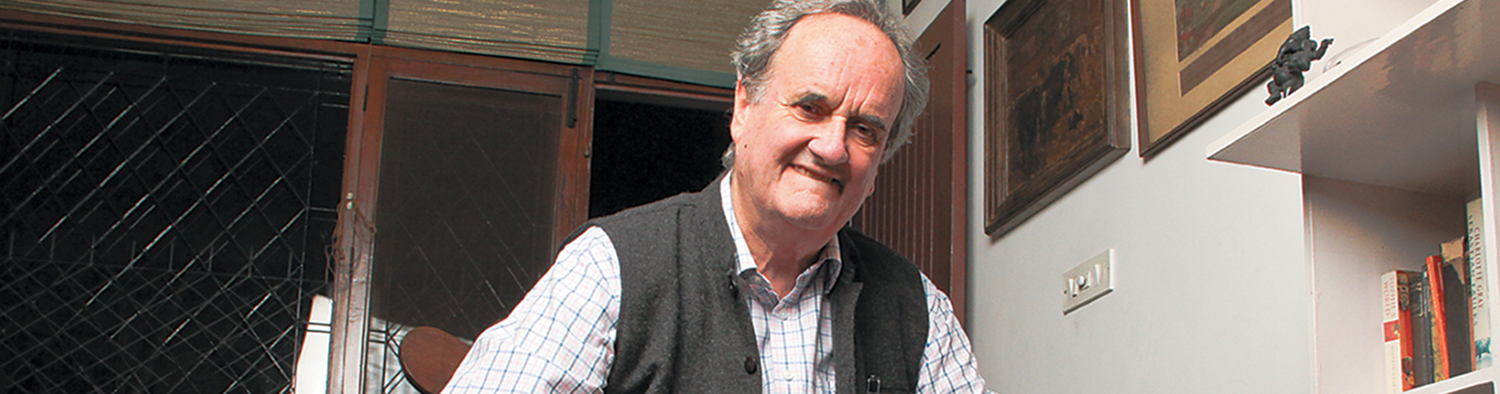

India with its chaos and challenges remains home for veteran journalist Mark Tully, discovers Sudha Tilak

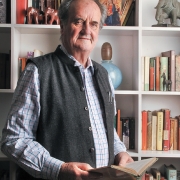

It’s easy to spot Sir William Mark Tully’s home in Delhi’s Nizamuddin West colony. As we navigate through narrow lanes, we spot a group of men in lungis and caps walking back from their namaaz. “The gora lives in the house with the red gate,” they point cheerfully with nods from rickshawallah. As we enter, we don’t hear the trusted voice of the BBC from India for over 30 years. Instead two healthy looking Labradors greet us with a volley of barks and some affectionate licks.

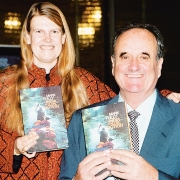

Today, even after his resignation from the BBC, Tully continues to be connected with the service. But his association with India goes beyond his work—his home is testimony to this. From his cup of Darjeeling and prints of old Calcutta (where he was born) and Gond paintings to his easy smattering of Hindustani while he speaks, this home, which he shares with his partner Gillian Wright, may well be the home of an Indian. Obviously, with Sir Tully, there are no full stops to his life in India. Excerpts from an extended conversation:

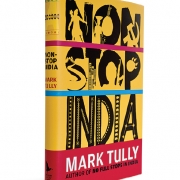

You wrote No Full Stops in India 20 years ago. And now your new offering Non Stop India has hit the stands. What’s been constant and what’s changed in these two decades?

We’d thought of the second book years ago. We’d wanted to see what things are like after 20 years. The fundamental difference in these years has been two contrasts: despair and passion. At that time during Licence Raj, it seemed that India didn’t go anywhere. Rajiv Gandhi succeeded a bit at leading the nation towards modernity. Twenty years since then we began to hear about ‘India the Great’, ‘the Great Hope’, ‘Future World Power’. We thought a look at all these changes will tell us if all this talk was valid. The more I thought of this kind of talk, I saw the danger in it, in that people will believe everything is fine. I think we have a whole lot of problems. Many people think that if we only attend to politicians and governance, things will be fine. There is also a lot of faith in luck and judgement that things will work out.

How long has this book been in the making? Is it a collection of your recent published work or the labour of your travels and reports specifically done for the book?

The book was longer than three years in the making. Our travels and reportage were largely for the book except the story of Tamil language issues in the state or the chapter on elections, which was done for a special report earlier. Most of the book’s travels were to learn first-hand about areas of governance that pose a major problem.

Your book warns about the breaks in this non-stop juggernaut called India including poor governance and jugaar, the attitude of a people who make do. How have you learnt to deal with this exasperating aspect of all these years of living and working in India?

My whole attitude to life has changed since moving into India. When I first landed here, if a train were two hours late it would exasperate me. Now I am OK with it. It does not frustrate me as it did before. It’s not that I like to sit back and enjoy it, but I see it as a matter of balance. It has a good side when you’re not too bound by time, efficiency, and it has a bad side that it seems to accept inefficiency. Rigid structures can shackle creativity. One of my favourite characters is the tentwallah from Monsoon Wedding who could improvise. That’s one of the things I love here.

Caste, vote-bank politics, environ-mental issues, language allegiance, televised Hindutva are part of the many concerns of the informed circle of India. What new insights did you want your book to reveal on these aspects?

With each chapter, I wanted to look at many issues of India anew. For example, religion is a bee in my bonnet. In a secular nation like India, I think religion is an irrelevant issue created by politicians on both sides of the major political parties. A party like the Congress ups these issues and the people let politicians get away. The reason I believe religion is of huge irrelevance to India is because I believe, fundamentally, a culture of religious pluralism exists in India.

Take the Maoist issue. So much of the talk ignores one or two simple facts relating to the support among the people: whether they receive wholehearted support from the forest people and the fact that we’ve had no huge uprising on their behalf. Much of the problem is due to old-fashioned policing and lack of governance in the Maoist areas. But the government has a different attitude towards Maoists. The police force needs massive reforms from above. The Maoist problem needs to be dealt in the right away. The answer is not sending in the CRPF. Similarly with regard to the Dalits and conversion, I believe we need to restore both their rights and pride in their community. I tried to look at things with a balanced perspective.

You worked with the BBC for three decades and resigned in 1994. How did you deal with that?

I began with the BBC as an administrator. Officially, my first radio piece was in 1962 when I was 32. I am a good example of jugaar! I never knew what I wanted to do before I became a journalist. Besides, I was also bad at typing so broadcasting suited me as I could read my typing. Unlike the computer where correction is easier, typing was a damn nuisance. Even today, I prefer to write by hand. One of the reasons I fought with the BBC before leaving was that I found the structure too constricting. That’s what happens when management structures interfere with a creative organisation. Perhaps the BBC needs some jugaar. In my speech, when I resigned, I had suggested there is a difference between biscuit-making and broadcasting. But it was a big decision to leave the BBC for me.

There has been vociferous protest about the BBC Hindi radio service shutting down. The BBC did and continues to evoke emotive responses of trust and affection among Indians. Have you had similar responses in your working years with the service?

The BBC is widely trusted in villages. I recall once asking villagers, ‘Why BBC?’ and they replied that the BBC gave them news that was true and sabse pehle [before anyone else]. This reputation was enhanced when Satish Jacob scooped the world with the news of Indira Gandhi’s assassination. A special reason in my days for that was that there was no alternative to government radio and the rural folk did look upon sarkari radio as being the government’s mouthpiece and not an independent voice.

One has many memories, especially the tumultuous time during Indira Gandhi’s rule. I remember her interview with me in 1983. It was the last I met her before she was assassinated and she did something she had never done before. After the interview, she asked me to switch off the recorder and said, ‘Talk to me’. And it was lovely as we had a free-wheeling talk.

I once went into a village with [Saeed] Naqvi and he asked a villager if he had any predictions about who would win the election; the villager replied that he had not heard the BBC and thus could not offer an opinion. You had that kind of faith from people that was truly humbling. I also remember the funny occasion during the Janata crisis over who would win. I walked into a political rally to have people boo us, crying, ‘Hai hai BBC, Tully Saab Murdabad’.

How did you feel about being the trusted face of the BBC?

Truly, what was important was that it didn’t go to my head. Satish and I were involved in the whole thing and I was only a part of a great institution called BBC World Service. It brought responsibility and fear; I knew that if something was reported wrong, the repercussions would be big.

What do you miss most?

The thing I miss most about the BBC is chasing the story. You felt always part of the pack and I enjoyed that. I had great times and fun with colleagues. I probably miss that the most.

What do you think is the most significant change in media and communication in India in the past two decades?

It’s harder to control the changes of today. The dangers in journalism are that mistakes are made, fear is created, and things are exaggerated in the name of breaking news, like in the case of 26/11 in Mumbai. Despite the ease of communication, the problem of the Internet is that material is published without journalistic filter. That means many people deliberately manufacture news. For example, we found that time and again rumours were put out on Hindu-Muslim riot figures that led to further unrest. Now, Twitter is on the job too. What is important is that media set these events in context; writing and broadcasting are responsibilities that need to be set in context so the medium can be trusted to put out verified news.

How many modern forms of communication do you use?

[Laughs] I don’t tweet or blog. I had an email a while ago that was floated claiming a despatch by me was untrue. I didn’t know how to stop it. Responding would have given it undue importance. That is the danger of the medium. As for Facebook, I don’t have the time because I have to churn out my bits and do my work.

You’ve received the Padmashri and Padma Bhushan, and you were knighted in 2002. What do these honours mean to you?

Obviously it would be ungenerous to say that I am not grateful for these honours. The more you get recognised, the more things happen. Somehow one is afraid that one is an ordinary person doing ordinary things; and why should one receive such honours? I can honestly say I am embarrassed though I am greatly grateful as well.

What are the best parts of living in India? Will you return to the UK?

I had no desire to leave the BBC or India. However it is 17 years since I resigned from the BBC and I’m quite well settled here. I never contemplate seriously about going back to England. Yet I will never say with finality that I won’t because as one who is believing of God’s hand, who knows what will come tomorrow? There is nothing that I dislike about India or Britain. I am seen as one who has cut off my links there and, horror of horrors, a person who is more desi than desis themselves!

You live in Delhi and have family in London. Do you get to meet your children and grandchildren as much as you would like?

I have four grandchildren. One of the minuses of my life is that I don’t get to spend as much time as I must with my children. Continuing to live and work in India meant less time spent with them. There is a cost to everything.

Woody Allen in his trademark moody pessimism said, “It’s a bad business of getting old, and I would advise you to avoid it.” What are your thoughts on turning old?

At 76, I am growing old. I can’t look back and say I’ve made big mistakes. Sometimes, like a good Hindu, I think I should stop writing, reading and retreat to thinking. Sometimes I do recall the beautiful countryside I grew up as a child in England and think I would like to spend my last days in the country. I do regret the passing of things. I am quite lame, growing hard of hearing, but age brings with it many compensations. When you look back, you realise some of your ambitions were stupid and all that goes away because you’re aware of the fleeting nature of life. The lovely thing about looking back is the many changes you’ve witnessed that your generation will miss. I’ve seen farming move from animals to tractors; I remember the beauty and power of watching the steam engines, the locomotives at the Howrah. I am delighted to have lived those times. There is sadness in it as well. A lot that was worthwhile has gone away from our lives.

How do you deal with the challenge of younger people looking at elders as outdated?

It is true. There is danger in England with ageism. It is important to get the balance right. One of the things I protested when I left the BBC was the fact that older correspondents were fired and their notion that the only correspondents who were worthy were in their 30s.

An old man like Anna Hazare has many youth drawn to him. Religion too has many followers among the young in India. Don’t we need younger people in Indian politics?

India has a traditional attitude to age. In the West, we find no respect for age. You can see it in the way grandchildren talk to their grandparents. I have always argued that insisting only on young people all the time is a huge mistake. We need a mix of elder people with valuable experience and bright young people who think they can turn things on the head. I am fundamentally religious. I go to church and am a member of the cathedral in Delhi. I like it that Indian youth think about religion or have respect for their elders. It’s a change from other sorts of goals of the western world. There, they are now going on a search for spirituality and having arguments about being religious and spiritual. I do believe that this aspect gives Indian youth an extra dimension to them. It can only be for their good.

What do you look forward to each day? Are you relishing the slow approach to savouring the day compared to the briskness of your younger working days?

I don’t have definite plans. I look forward to the Sunday morning programmes I do for the BBC and would like them to continue. I don’t want to write a column as it would be too constraining and I would be forced to say something each week.

The year 2012 is upon us. It has been variously called a year of apocalyptic upheavals and portends. Tell us about a wish list for the year ahead.

[Laughs and thinks hard] Umm…get up early and do more yoga regularly.

Photos: Shivay Bhandari Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine January 2012

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….