People

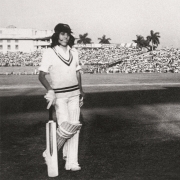

Diana Edulji, 61, Mumbai

Member of the first Indian women’s cricket team

In 1975, the Indian women’s cricket team stepped onto the lush turf of Kolkata’s Eden Gardens for the first time. The match, against Australia, was a part of the team’s first international Test series, a first also for one of their team members.

In front of 10,000 spectators, 19 year-old Diana Edulji, left-arm orthodox bowler, participated in her international debut series. The following year, in a match against the West Indies in Patna, Edulji racked up her personal best as a bowler: 6 wickets for 64 runs. “I also hit the winning stroke and notched up my highest score in Test cricket, 57 not out.” This match was India’s first international win.

On the field, Edulji made her name as India’s highest wicket-taker (currently No. 3 in the world) with 66 wickets in a Test career that spanned 20 years. She was the star bowler in India’s first women’s cricket team and also became the ODI captain—a position she held on and off for 15 years—just in time for the 1978 World Cup.

Edulji always wanted to be a bowler. As a young girl, she spent her weekends playing tennis ball cricket. She was the only girl playing with 10 boys at the railway colony in Bombay, where she grew up. One of the few times she picked up the bat was when they decided to experiment with a season ball. Things went a bit awry and Edulji ended up losing her top incisors even before her professional career began!

Women’s cricket in Bombay started in 1969. “Mrs Aloo Bamjee, an old Parsi lady, formed a club and recruited local girls. I joined in 1971, at the age of 15 or 16,” she recalls. “It was the first time I was meeting lots of girls who played cricket.”

Owing to her tight, almost stingy, bowling, Edulji was the only woman cricketer permitted to bowl to visiting foreign teams during their practice sessions. She played her first Nationals in 1974 as part of the winning Bombay team. (“I got to skip my Metric prelims to play the Nationals!”) She joined Jai Hind College but dropped out after her first year, when she was appointed by the Western Railway in the sports quota. As sports officer, she recruited more women players to join the Railways. “Today, over 95 per cent of the girls playing cricket are employed by the Indian Railways and its various branches. It is the only organisation that gives women cricketers jobs.”

Edulji retired from international cricket in 1995 but continued to play domestic cricket till 2000, well into her 40s. That’s when her second innings began—off the field—when she took up the cause of women’s cricket with gusto. She was known for her fiercely honest voice, and whether taking on the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) or on tour overseas, she has never backed down from a good fight. “When we were touring England in 1986, they didn’t let us into the Lord’s Pavilion. It was quite typical of them. So when speaking to the BBC, I said to the Marylebone Cricket Club, that if you think of changing your name from MCC, you should consider ‘MCP’, for ‘Male Chauvinist Pigs’. ”

It was this attitude that would ably assist her back home, where people at the helm—from players to the cricketing bureaucracy—would publicly opine that women should not play cricket, let alone be paid for it. With stakes so frivolous, their reputation was all they cared for and Edulji and her teammates roughed it out in the unreserved ladies’ compartments in trains (“We’d have fist fights with the other passengers”), their bulky kit bags in tow, travelling the length and breadth of India. And together they raised funds to tour India and the world, including the three months they toured the West Indies, England, the Netherlands and the US.

Edulji’s battles with bureaucracy continued long after her retirement from professional cricket. And she used her position as a sports officer in the Western Railway to develop women’s cricket. “Diana’s greatest contribution to Indian cricket is the number of girls she has brought into the game,” says Shanta Rangaswamy, former India Test captain and Edulji’s teammate for over 20 years. “I think around 500 women have been given job security by the Railways, enabling a whole generation of them to develop women’s cricket.”

In 2006, when the International Women’s Cricket Council merged with the International Cricket Council (ICC), national cricket organisations were instructed to merge with their women’s association if they wanted a seat in the ICC. Thus, despite stiff opposition, the Women’s Cricket Association in India was merged with the BCCI.

A few weeks ago, Edulji was appointed by the Supreme Court as one of the four members of the BCCI Working Committee. Being the only former cricketer on the board in charge of crucial reforms to be implemented in the national and state cricket associations is a rare privilege.

Indeed, Edulji will go down in history as a pioneer of women’s cricket in India. Rangaswamy sums it up nicely. “Statistics don’t portray the full picture. Our biggest achievement is that when we started, we could stand shoulder to shoulder with the teams around the world. We laid a solid foundation and ensured the longevity of the game.” Now, the woman who finally sits on the all-powerful Working Committee of Indian cricket’s governing body says, “This should shake the BCCI out of its slumber.”

- My success story: “In school, I played basketball and table tennis at the junior state level. But for a career, I had my mind set on cricket. Looking back, I know I made the right decision.”

- The inspiration behind it: “I was inspired by English cricketer Rachel Heyhoe Flint [who passed away this January]. She got the Lords Pavilion to open its gates for women’s cricket. If she could do it there, I wanted to be the person here to break all the barriers.”

- Challenges: “We had to beg for what we wanted every step of the way. But in the face of such resistance, our love for the game motivated and united us.”

- Lessons learnt: “All the time I’ve spent breaking my head with bureaucrats has prepared me to take up this very crucial job as member of the current BCCI Working Committee.”

- Aspirations, goals and vision: “To develop women’s cricket in India. It begins with recruiting players young and providing them with job security; paying players a viable fee for every match played; and paying all past players who have represented India, even for a single match, a one-time benefit.”

- The way forward: “As a member of the Committee, I am in charge of interpreting and implementing crucial reforms, one of which is the recruitment of a woman player onto the boards of state and national cricketing associations.”

- Awards & achievements: Padma Shri (2002); Maharashtra Gaurav Puraskar (1991); Arjuna Award by the Government of India (1983)

—Natasha Rego

Photo: Natasha Rego Archival images courtesy: Diana Edulji Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine March 2017

GUTS & GLORY

NO FORMULA HERE

OH, BABY!

I SPY

MARTIAL LAW

AT THE WHEEL

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….