People

Banno Begum thought her career had ended when colonial rule drew to a close, only to make a comeback that took her to greater heights, writes Zakir Hussain

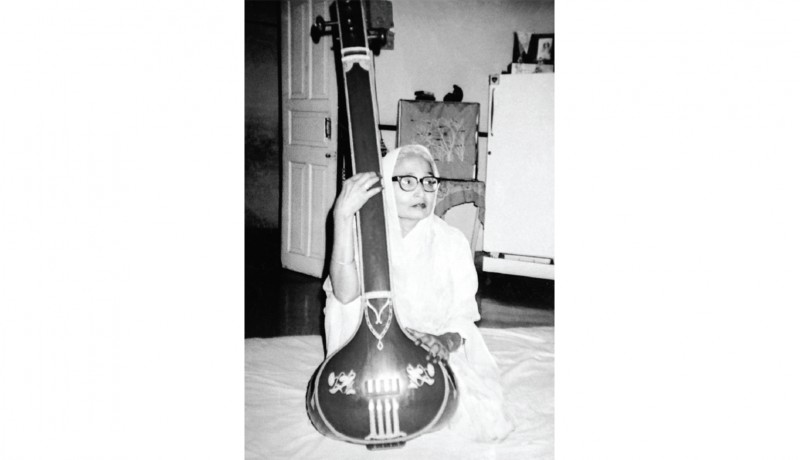

It’s not often that you get to serenade a queen, not even when you’re a celebrated musician. Banno Begum, now 84 years old, remembers her encounter with Queen Elizabeth II, more than 50 years ago, with distinct clarity. An exponent of maand, a type of Rajasthani folk singing, she’s also regaled presidents and prime ministers, both Indian and foreign, and performed for maharajas, aristocrats and nobility.

Maand falls into a nebulous category between classical and semi-classical Indian music, and is just as difficult to master as any classical raga. As a student, Banno Begum passed every test with flying colours before she was appointed to the Jaipur Raj Durbar.

Banno Begum inherited her extraordinary vocal talent from her mother, Gauhar Jaan, also a singer and a dancer who performed for the maharajas of her time. But it was Ustad Nazir Khan, a well-known sitar exponent, who led the 11 year-old to the peak of her talent. “In those days, the shagird [disciples] were expected to stay with their ustad [musical gurus] during the learning period,” she recalls. “And even though I was married to Thakur Kishangarh Singh Rathaur, himself a man of music, he supported my education.” Under the tutelage of Ustad Nazir Khan, Banno Begum learnt different styles of folk music and became proficient in singing maand, ghazal, thumri, dadra, rasiya, hori and khyal.

“Back then, our ustad not only educated us in music but groomed us in speech, dressing sense and etiquette,” she adds. The values and lessons she learnt have clearly stayed with her as the legendary singer is still mindful that her pallu should not slip off her head. Banno Begum recalls how children from royal households were sent to her to be educated in genteel manners and behaviour fit for a court. “What we learnt as children, we are still passing on to the coming generations by mindfully practising it ourselves.”

As time went by, Banno Begum’s music slowly gained recognition and she found herself in the Gunijan Khana of Dantaramgarh, in Sikar, Rajasthan. Gunijan Khana was a department created by the erstwhile rulers to patronise the crafts and their practitioners, and this was where Banno Begum met other big names like Badfi Gauhar Bai, Farhad Jahan Bibo and Gauhar Benazir, who became her contemporaries.

“Our performances were majestic,” reminisces Banno Begum. “Only the thakurs who owned 50 to 200 villages could attend musical programmes in the Raj Durbar,” she says, also recalling the etiquette one had to follow as part of the durbar. “At the end of the programme, no one was allowed to clap. The music was enjoyed along with beverages. The programmes were organised on the roof of the City Palace, the spot from where Govind Devji’s temple was visible and we would all pay our respects daily.”

Speaking of performances of yesteryear, she says she still has a gold asharfi (coin) presented to her by the Thakur of Mukundgarh in appreciation of her singing. Then, with a twinkle in her eyes, she recalls a mehfil (musical gathering) in Naina Devi’s house that Maharaja Bhawani Singh had presided over as a special guest. Seeing him, Naina Devi came over to her and whispered in her ear, “Apke maharaj tashrif le aaye hain lekin aap gaate-gaate khade mat hona.” (Your king has arrived but you need not stand up while singing.) Maharaja Bhawani Singh was mesmerised by her hypnotic voice the entire evening.

Banno Begum looks back wistfully at those heady times. “The Raj went and along with it all the positions of the Raj. And this exposed us to the world outside. One instance was when Mirza Ismail, Diwan of the kingdoms of Mysore, Jaipur and Hyderabad, issued an order to vacate Hada Bazaar in Ramganj, which was allotted to concubines and artists.” A proud Banno Begum refused, pointing out that the Maharaja himself had given them permission to stay. “This caused a furore in the bazaar and only after some cajoling did Diwan saab agree to host an audition and decide the fate of us artists who stayed there. I proved my mettle and was allowed to stay.”

The legendary vocalist says India’s colonial rulers were true patrons of the arts. “Once they left, there was a decline in the classical style of music and I didn’t feel like I belonged anymore, so I stopped practising.” However, her sabbatical was short lived as Rajasthani author and politician Padma Shri Lakshmi Kumari Choodawat, a fan of Banno Begum’s singing, encouraged her to re-establish herself in a different style. “She loved my singing, and would always come and pay her respects whenever she was present at my shows. So when I gave up music, she suggested I grow with the times instead.”

In her late 50s, Banno Begum was determined to kick-start her career once again. She immersed herself in her music and, soon, word spread. “The world of Indian folk music was much smaller then,” she points out. Apart from singing for dignitaries, she sang for All India Radio, out of its Delhi and Jaipur stations. She was also appointed as an instructor for maand gayaki by the Uttar Madhya Sanskriti Kendra, also known as the North Central Zone Cultural Centre.

Banno Begum may have been pining for the glory days of the Raj but her tryst with India’s colonial rulers had not yet ended. One of the highlights of her career, after the Raj, is her encounter with Queen Elizabeth II, for whom Maharaja Man Singh hosted a party at Rambagh Palace, Jaipur during the Queen’s 1961 India tour.

As part of the functions organised by the Maharaja, Banno Begum had been invited to sing maand on the occasion. “The dress code was strictly followed, which was full regalia: bajuband with kundan work and a basra pearl necklace with both pukhraj and diamonds. Queen Elizabeth came close to me and asked about my necklace. I didn’t know any English, so I asked one of the officers standing there to explain what she had just said. I understood that she liked my necklace, so I took it off and presented it to her. She wore the piece then and there,” says Banno Begum, smiling at the recollection.

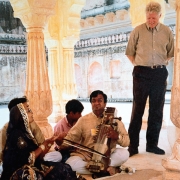

Banno Begum also remembers being invited to the wedding of the daughter of then president of India Dr Zakir Husain Khan. “The audience was frantic when I sang Chand ki raat and Sejariya kyu na padharo in maand style,” she recollects. Former US president Bill Clinton was also treated to Banno Begum’s vocal talent during his visit to Jaipur in 2000, when she performed her rendition of Padharo mhare desh. Actor Akbar Khan and singer Noor Jehan have attended her concerts, along with other famous names like poet Hasrat Jaipuri, Saghar Siddiqui Sahib, Bashir Badr and Kathak maestro Hanuman Prasad.

Although hard of hearing now and frail, the vocalist still displays flashes of gumption and the regal air that envelopes her is evident every time she speaks. She has two albums to her credit: Maand Gayika: A Banno Begum Niazi and a five-hour collection of Rajasthani maand songs called Kesariya Balam in collaboration with singers like Jamila Bai and Kulsum Bai. They offer but a fleeting glimpse into the life and work of Banno Begum, a voice that will not be stilled.

Photos courtesy: Zakir Hussain Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine September 2018

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….