People

True to form, Padma Shri Pankaj Udhas’s latest album Sentimental is winning the hearts of ghazal lovers, world over. Deepa Ramakrishnan meets the maestro who has always marched to his own beat, through adversity and applause

The hustle and bustle of Mumbai hasn’t found its way into the tranquil and tastefully appointed home of Padma Shri Pankaj Udhas in South Mumbai’s Peddar Road. “My dad will join you shortly,” says Nayaab, his elder daughter, as she ushers us into the living room and asks after our refreshments. The sober walls in his home match the light Victorian furniture, crystal curios shimmer, and well-tended potted palms lend a burst of colour. It’s easy to take in the unhurried feel of the home where even time seems to have slowed down a beat.

Indeed, Udhas’s oeuvre, spanning 30 years and close to 50 albums, seems to have transcended time. An entire generation grew up listening to his voice. His first ghazal album Aahat was released in 1980; more albums followed, some as successful, others even more. But it was not until 1986, with his soulful rendition of Chitti aayi hai in the Hindi film Naam, that people really took notice of his silken voice. Thereon, a constant, joyous drizzle of melodious renditions, ghazal and ghazalnuma film songs made him an integral part of the lives of music lovers. In the 1990s, he scaled musical peaks, taking the ghazal to new heights, breaking conventions, making foray into media territory yet uncharted. In 1999, Udhas went on to host a popular ghazal talent-hunt show Adaab Arz Hain, on Sony Entertainment Network and his expertise was also sought for judging another musical contest, Meri Awaaz Suno, then hosted by Bollywood playback singer Sonu Nigam. About 11 years ago, he began conducting Khazaana, an annual two-day ghazal festival to recognise stalwarts and raise funds in aid of cancer and thalassemia patients, a cause he is very passionate about.

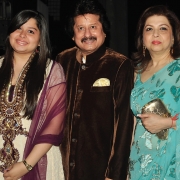

My thoughts are interrupted as the maestro joins us. He is dressed simply, yet elegantly, in a jet black chudidaar-kurta and light turquoise, silk Nehru jacket with light paisley patterns. At 62, it’s not surprising to see age showing on the graceful face but the years haven’t taken away the warmth of his smile that still reaches his eyes. After the introductions are made, we settle down, even as the photographer readies his lights for the shoot.

A SENTIMENTAL TURN

Udhas has returned only a couple of days ago from a successful tour of the US to promote his latest ghazal album Sentimental, which was launched by his music company Velvet Voices Pvt Ltd in late July this year at Khazaana, a week before his tour. “I’ve been travelling to the US since the 1980s and have a good following in the US and Canada,” he says. “I usually tour the country in March-April but this time, we were there in August-September, a period when schools are about to open after their vacations. So there was a risk of low attendance owing to people holidaying or preparing for school reopening. However, throughout the tour, most of the halls were overbooked, and every concert went off to a packed house.”

Sentimental had not really been tested in India because of time constraints, but the US tour appeared to have served as a litmus test. “In the beginning, we rehearsed two popular numbers from the album for the tour. But soon, we were rehearsing a third and then a fourth one. At some point during the tour, I was singing five songs out of the whole album,” he says, laughing, the pride of having conceived yet another wonder showing clearly.

Incidentally, Sentimental was released close on the heels of Hey Krishna, his first bhajan album after he had rendered the Hanuman Chalisa in the wake of the 26/11 attacks in 2008. Hey Krishna had been arranged by his London-based nephew Kartik Udhas, who had introduced contemporary flavour in the interludes and percussion. So did he also promote this album during this trip? “No,” he replies. “Bhajan is a very private aspect of me. And I have never mixed bhajan and ghazal during my tours.’

ANOTHER MASTERPIECE

According to reports, Maaee, a number from Sentimental, seems to be steadily garnering the kind of fame that Chitti aayi hai had brought him. You read about the emotional responses the song evokes among audiences…grown men and women, sobbing openly to the touching lyrics by poet Tahir Faraz, some overwhelmed, choking on their tears, others discreetly trying to wipe away a stream building at the corner of their eyes. Udhas even tells us of a man who hadn’t been able to meet his mother in India for about 14 years because of clearance issues in Canada; he had sobbed shamelessly at a concert. Was he expecting that kind of reaction when he composed the music for it? “I knew while composing Maaee that it would go down well with audiences,” he acknowledges. “I actually anticipated that kind of reaction and decided to sing Chitti aayi hai much after Maaee—just to give enough time for people to recover.”

It brings to mind what he told me in an earlier interview, about composing music using his own cues. “Making music thinking of what people might like can be your downfall,” he had said. “You must be true to your core and feel one with the music.” Interestingly, he had taken about three days to work out the music score for Maaee. And going by the standing ovations it has received, the effort has paid off. Also, a nazm in the album, Tum joh hasti ho to phullon ki yaad, has been widely appreciated by musicians for its chord progression. But then, the ghazal maestro has always been a composer, not a writer. “I am very passionate about composing and I am confident about my abilities to do so,” he says, explaining the inspiration for Sentimental. “And though I had rendered two very beautiful albums that did very well, Shaayar [2010] and Dastakhat [2012], they were not my compositions. I have been quite busy for the past few years and there was a huge time gap since I last composed. That alone drove Sentimental.”

Udhas is also a lover of poetry and is always on the lookout for good poems—sometimes getting them from completed works of old poets, called the Khuliyat, or choosing from works of well-known contemporary poets. But for someone who does such justice to the poetry he sings, why doesn’t he write any? “Urdu poetry is very difficult to write, with rigid meters around which to create a verse,” he had told me. “It’s a complete art, something I haven’t ventured into.”

THE PRODIGAL SONGSTER

Born in 1951 in Jetpur, Gujarat, Udhas was about five years old when he was subtly initiated into music by his father’s interest in learning and playing an instrument called the dilruba. Every evening, his dad would return from work and sit down to tune his dilruba, playing it for about an hour.

Soon enough, Udhas realised his passion was music. And because his father loved music, he never discouraged his three sons—Manhar, Nirmal and Pankaj—from their musical aspirations. At the age of 12, Udhas enrolled to learn the tabla at Sangeet Natya Akademi in Rajkot, close to his birthplace. There, he was exposed to classical vocals and became fascinated. The family soon moved to Mumbai, where Udhas was mentored by Navrang Nadpurkar, a child prodigy and brilliant vocalist, fondly known as Master Navrang. And after he was introduced to Begum Akhtar’s ghazal, he knew that’s what he wanted to sing, with Master Navrang in full accord.

Manhar, his eldest brother, was already singing for films. And Udhas, who was studying science in St Xavier’s College, realised that in order to do justice to the ghazal, it was important to get the diction and pronunciation right—by learning Urdu. So he tagged along with his big brother to an Urdu teacher, known simply as Maulavi Saab. “I was fascinated by the language and more so by the Mirza Ghalib poetry Maulavi Saab used to quote when teaching Manhar,” remembers Udhas. He soon gathered courage and approached the maulavi to teach him too. As hard as it may be today to visualise a hippy-happy Udhas, it was precisely how the maulavi first saw him—with long hair, dressed in a long kurta and bell-bottomed trousers paired with chunky jewellery. But after some convincing, the teacher consented and his training began.

A FLAILING START

Although Udhas’s career officially started in 1980 with the release of his first ghazal album Aahat, he had been active in the music scene much earlier. “I had sung through school and college, and by the late 1960s, Manhar, Nirmal and I formed a band called the Fabulous Three Brothers, doing concerts with a complete orchestra,” he says.

After hearing him at one of these shows, music composer Usha Khanna recommended Udhas to firebrand filmmaker B R Ishaara, who had directed the controversial movie, Chetana (1970). Ishaara was taking on a new crew for his latest film Kaamna, and looking for new singers too. He hadn’t wanted to try out singers like the Late Jagjit Singh either, as he had already sung a couple of film songs, and Ishaara had wanted to use a new voice. “I was asked to audition at the now-defunct Famous Studios,” remembers Udhas.

“I got through the auditions easily and was asked to come back the next day for the recording. The moment I stood before the mike, the brashness I felt during my audition vaporised and nervousness engulfed me—this was where stalwarts like Mohammed Rafi, Kishore Kumar and Manna Dey sang their songs…where Raj Kapoor recorded all his films’ songs. But thankfully, I did well and the song, Tum kabhi saamne aajaao to poochoon tumse, was well-accepted.” With rave reviews coming his way, Udhas imagined he had made it.

But fate had other plans. “I struggled for almost 10 years after that,” he reveals. “Despite the song’s success, the film industry didn’t want newcomers. Today Bollywood is open to different voices; back then, the industry wanted just Rafi saab, Kishoreda, Manna Dey and Mukesh, who were actually really very good and delivered exactly what was asked of them. My preoccupation with music left me with no time for anything else. I had no job or business to depend on.”

And though Udhas did concerts across the country and in the US and the UK, he was struggling. In fact, there came a time when a frustrated Udhas decided to leave it all behind and move to Canada for good. But once there, he realised how much Indian music was appreciated and he knew it was time to get back to where he belonged. “Also, every time I sang, the responses I got were wonderfully positive,” he remembers. “That positivism just kept me going.”

THE REVENUE CAPITAL

Udhas did decide, however, that films were definitely not his platform—he loved ghazal more. In 1980, he launched his first album, Aahat. “I did nothing in films for a while, indulging only in ghazal,” he recollects.

Then, in 1985, he released Nayaab, the first-ever album to be recorded on multi-track. Loaded with gems like Zamaana kharaab hain and Ek taraf uska ghar, it was a chartbuster, staying at the top of the music charts for over six months. In fact, Nayaab was pre-booked at music stores—even on the day the album hit stores across the country, none of them had a single copy left to sell. “That was when the film industry took notice of me,” remembers Udhas. In 1986, he was signed up to sing Chitti aayi hai, which carried his silken voice to a wider audience, his poignant rendition melting hearts across the world. In poured a stream of offers—Jeeyen to jeeyen kaise (Saajan, 1991), Na kajare ki dhar (Mohra, 1994)—and Pankaj Udhas had arrived.

His loyalties, though, remained with the ghazal. Following the stupendous success of Nayaab, his music company insisted he do his next album, Afreen, as an extended version—a 90-minute, double-cassette format instead of the standard 45 minutes. Like everything he touched, Afreen too turned gold, selling 1.2 million copies in 10 days, perhaps one of the highest selling ghazal albums to date.

SHIFTING WINDS

The 1990s were also the years when Indian television began to explore the possibility of playing all kinds of music. But in the early part of the decade, MTV didn’t play anything but western or Bollywood numbers. Udhas, who has never shied away from trying something new, approached the channel with his music company Music India (now Universal Music India) and the Indian Music Industry (IMI) to consider running his videos on air. It was only some years later, in 1999, that they agreed to air the video of one of his ghazal, Phir haath mein sharaab hai, from the album Nasha. It was a move that brought a flush of non-Bollywood videos to television.

But soon, tastes changed and people moved on. Or, perhaps, models of revenue-generation changed and TV channels moved on. “Today, musicians are deprived of that huge marketing arm, the television, and they’re where they were before TV channels helped them reach their audiences,” says Udhas, the regret sharp in his voice. “Despite the latest technological trends, nothing compares to the wonders of a TV remote. Even musical reality TV shows have audiences chanting the names of the contestants. No matter how popular YouTube and such become, nothing will replace the TV.” Then, snapping out of his thoughts, he adds, “The period since the 2000s has been the worst time for musicians playing non-Bollywood music in our country; it’s a very scary situation. And Bollywood music today has turned into a confused genre—a mix of hip-hop and R&B.”

And yet the disdain for the loss of a platform for his beloved ghazal hasn’t turned him bitter about other musicians—or genres. One remembers the controversy that erupted when the late Jagjit Singh, his fellow ghazal maestro, dismissed A R Rahman’s Oscar for the score of Slumdog Millionaire, saying, “Ask him to compose a ghazal, and then we shall see.” Udhas feels differently. “I don’t think anyone can claim that their genre of music is any better than another’s,” he insists. “Composing music is challenging, no matter what the genre; it’s not correct to belittle another’s efforts and compositions.”

He has less respect for the rash of music contests on TV today, despite his experience judging Adaab Arz Hain and Meri Awaaz Suno. “Those shows were about music alone,” he underlines. “I stopped wanting to be a part of such reality shows after they became about TRPs and SMS voting and tears and drama on stage. In fact, though the judges on Adaab Arz Hain were not paid money, save for transportation and refreshments on set, we had people like Naushad and Khayyam Saab happily being a part of the show. These shows are a great platform for talent. But nowadays, even the TV channels want nothing to do with the winner as the season ends. And especially because I have lived through that struggle, it feels wrong that despite the stardom, those winners aren’t acknowledged thereon. Sure, the money is a huge draw and there is that added advantage of millions seeing you as a judge, but I am well on both counts on my own accord.” Would he then consider turning mentor? “I don’t think I have learnt enough music to be able to teach anyone,” he says modestly. “But I have considered building a music institute that teaches music with a proper syllabus. Maybe that someday.”

REWARDS AND REGRET

It’s a dream commensurate with his tremendous success. Udhas has won about 18 awards, including the Padma Shri in 2006, the year he completed 25 years in the field. “The honour is yet to sink in though, yes, all those early years of struggle feel vindicated,” he says with a smile. “But I owe it to the late Vilasrao Deshmukh, who was then chief minister of Maharashtra. He was a fan and went out of his way to nominate me.”

Although he insists that awards don’t really reflect one’s worth or talent, he does have one regret. “Chitti aayi hain, in 1986, turned out to be a landmark hit, and in all fairness I believed I should’ve got the Filmfare Award for it,” he confesses with a chuckle. “But sadly, for some reason the Filmfare Awards weren’t given that year [1987]. Despite every other award I’ve won or missed, that award was one I really felt deprived of!”

TRANSCENDING TIME

“Besides Jagjit Singh, Pankaj Udhas was the only one who led the pack of ghazal singers so well, and stayed around for so long,” says Mehmood Curmally, managing director of Rhythm House, a landmark music store in Mumbai’s Kala Ghoda area. “What set him apart was the effort he put into advertising too. We would have autograph sessions with him at the store where he would arrive immaculately dressed, hair in place, and sit for hours signing autographs. He was always such a gentleman, always humouring his fans. Although there isn’t much of a craze for ghazal these days, I hear he still has quite a hold on his fans—his concerts are still running full.”

Vijay Lazarus, president of the Indian Music Industry, a trust that represents recording industry distributors in India, is widely credited with introducing ghazal and bhajan into the popular music scene in India when he was head of Music India. “By the 1980s and 1990s, there was a dearth of good music,” he recalls. “Bollywood had started getting more action-oriented and there was a vacuum of lyrics as well as melody. So we began approaching young ghazal singers like Pankaj Udhas. His tunes and style helped the ghazal penetrate deeper into the mass market, making not only the voices of the singers but also their faces popular— they didn’t need an actor’s face to sing for, as in the movies. Ghazal began garnering a larger market than Bollywood music. Today, with different kinds of music as well as outlets to hear or download music, ghazal has gone back to becoming simply a genre, although with a niche of its own. But going by the acceptance for his latest albums, I think Udhas is still very relevant and, perhaps, one of the most popular ghazal singers today.”

Indeed, it’s been over 25 years since Chitti aayi hai, and his voice remains as youthful. Point that out and Udhas replies, “A singer’s life is perhaps the worst—all you have is your voice! Anyone who listens to you expects 130 per cent from you, always. I follow a lot of dos and don’ts to maintain my voice, including tips from noted otolaryngologist Robert Thayer Sataloff. I avoid cold water, eat carefully and take bland food, especially before a concert. Rich and spicy food causes acidity, which can affect the vocal chords. But my daily, hour-long riyaaz has helped me the most.” Ask him when he ate his last ice-cream (something he admits he loves) and he cannot remember. “I guess I love singing more than ice-cream,” he adds, chuckling.

But it’s not just about his voice—there’s been no perceptible dip in his energy through the years either. “I strongly believe age is in the mind,” he asserts. “In fact, the tour I just returned from was very strenuous. I’d sing on Friday night, travel all through the next morning to the next destination and then sing again that night only to repeat the whole routine again the next day. But I’d do it all over again. The moment you think of retiring, age catches up with you. Singing keeps me young.” Udhas also follows a two-hour fitness schedule every day, an hour of walking and yoga each. “It keeps me feeling active through the day,” he explains. “Moreover, unfit and fat bodies can create breathing trouble, something a singer cannot afford.”

ANCHORS AHOY!

Other than his passion for work, Udhas’s close-knit family—Farida, his beautiful wife of 31 years and two daughters—sustains him emotionally. He met Farida at a neighbour’s house in 1979, during his darkest period of struggle. “I don’t think I have felt that kind of despair ever in my life; it was all-pervading, consuming me totally,” he remembers. “I found Farida to be focused, with a lot of faith in me and my abilities even when I had nothing going for me.” By and by, she turned into his “anchor”.

“It may not have been easy for her to start the relationship because she came from a very affluent family and had no dearth of suitable men. But if she hears me saying this, she will scream at me,” says Udhas, his light laughter not hiding the love and respect he feels for his better half, the woman he often refers to as his best friend. “In fact, initially her parents were against it but I hadn’t wanted to marry her without their permission. So I met her father and he agreed, though reluctantly. Today, I am his favourite son-in-law,” he adds, smiling.

Although Farida is not trained in music, Udhas credits her with a keen ear. “She has always had this ‘sixth sense’, knowing which melody will work and which won’t,” he reveals. “And I have come to trust that.”

When Udhas is not touring, his evenings, before he begins his composing sessions, are reserved for his daughters Nayaab, 27, who runs an event management company, and Rewa, 19, a student of mass communication. Nayaab, who was named after his album, looks after Udhas’s national and international concerts. “He is an amazing dad,” she says. “Despite his schedule and concerts, he always makes it a point to be there for us. In fact, when I was little and getting admitted to school, the school insisted both parents be there at the interview. My father was out of town for a concert; yet, he travelled through the night to ensure he was there for the interview, reaching the school directly from the railway station.”

To his daughters, Udhas is more friend than father. “He is always up-to-date with the times, whether it is current events, technology or the latest movies and music,” adds Nayaab. “Even my friends get along really well with him. Professionally, I have learnt a lot from him—his temperament, his commitment to honour his word and the need to reach out to help someone in distress.” So are Nayaab and Rewa musically inclined? “Both of us love music but neither of us wanted to pursue it,” she responds. “People around us wonder why we weren’t doing justice to his legacy, but never once did he force either of us into riyaaz or to take music more seriously.”

For his part, Udhas says, “It doesn’t matter to me. Because I know that music needs to come from within.” No one knows it better.

Photo: Vilas Kalgutker Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine November 2013

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….