People

The tiger stands on the brink of extinction in India, but tiger conservationist Valmik Thapar refuses to abandon hope, writes Rajashree Balaram

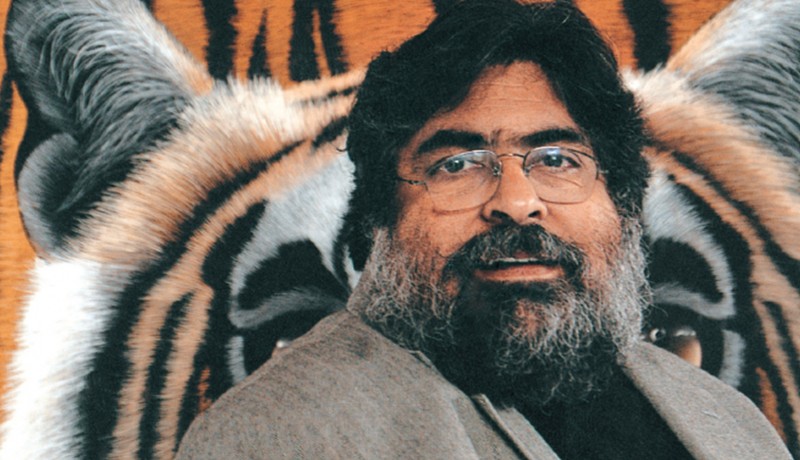

The meeting is scheduled for 10.30 am. I enter the gates of Valmik Thapar’s bungalow in Delhi’s posh Maharani Bagh area 10 minutes ahead of schedule and find Thapar prowling the driveway waiting to meet me. He is not over-eager; instead he looks like he can’t wait to get it over with. As I meet his fierce, intent gaze, I am reminded of all the adjectives the press has often used to describe Thapar: abrasive, combative, contentious and reclusive.

Thapar does not believe in small talk or trivial niceties — we start the interview two minutes after I greet him. His hefty frame is intimidating even when seated; his baritone feral even at its lowest pitch. Clad in casual shirt, trousers and chappal, the 55 year-old refuses to dress up for the photo shoot. After some coaxing, he shrugs into a black jacket.

As birdsound wafts across the lawns and two garden lizards stare down from the ceiling of the verandah, it occurs to me that meeting Thapar is no less unnerving than facing the tiger. He admits he does not smile much. But after spending the past 33 years striving to save the tiger, Thapar finds little reason to be cheerful standing in the middle of the appalling wildlife scenario in India. From an estimated 40,000 tigers in the beginning of the 20th century, the tiger population in India has plunged to 1,411, as declared by the National Tiger Conservation Authority of India in February 2008.

Is the situation utterly hopeless? “If you had asked me the same question last year, I would have readily admitted to hopelessness and misery,” says Thapar. “But NDTV’s aggressive ‘Save the Tiger’ campaign followed by the finance minister’s recent announcement of a Rs 500 million grant to the National Tiger Conservation Authority makes me cling on to hope.” The bulk of the grant will be utilised to raise, arm and deploy a special Tiger Protection Force.

Slim silver lining apart, Thapar continues his crusade tirelessly. A day before meeting Harmony, he was at the Carl Zeiss Wildlife Conservation Awards where he discussed the magnitude of the wildlife crisis with Union Minister for Science and Technology Kapil Sibal — Thapar has been part of the awards’ jury for the past eight years. In April, he will be in Brussels to speak about tigers to select members of the European parliament, an event similar to the one in The Hague last year where he raised the decibels against China’s exploitation of tigers. Between talks, conferences and seminars, Thapar fires countless letters to heads of state urging for proactive measures to curb the crisis. Besides making recommendations to Prime Minister Manmohan Singh on wildlife affairs, he is a member of several wildlife organisations and committees — National Board of Wildlife, International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Cat Specialist Group, Steering Committee for Determining Critical Wildlife Habitats under the Tribal Rights Act, and till last month the Central Empowered Committee instituted by the Supreme Court. (“I have been part of more than 150 federal and central wildlife committees so far.”). The irony of his situation doesn’t escape him though — though his wisdom on tigers makes him a much sought-after figure on almost every wildlife committee, his expert recommendations usually run into a hard wall of government indifference and sloth.

For over a decade now, Thapar has paced the corridors of power trying to convince prime ministers, chief ministers and bureaucrats about the urgency to save the tiger. He has walked away from countless meetings astounded by the bureaucratic morass, corruption and official apathy that block his mission. In his book The Last Tiger, Thapar has named two prime ministers who slept through a meeting convened with members of the forests and wildlife authorities.

In a way, he has grown up learning to steel himself against administrative lethargy. He was raised in the political thickets of Delhi; his mother Raj and father Romesh Thapar, both journalists, were close friends of Indira Gandhi. Such proximity to power circles afforded him a ringside view of the political circus very early in life. He had clear insights into how politics worked — or rather how it didn’t. In typical rebellion that has marked much of his life, he refused a cushy job with Shriram Chemicals after topping Delhi University in sociology. “I couldn’t imagine myself doing anything in the corporate world.” Still in search of that indefinable mission, he dabbled in photography, then went on to make several documentary films — many of which won national and international awards.

It was while filming one such documentary, Deep in the Jungles of Rajasthan, that he first came to Ranthambore Wildlife Reserve. A seemingly ordinary visit that changed his life and the way he viewed the world.

“I started spending more time at Ranthambore,” reminisces Thapar. “So much so, that my parents wondered why I disappeared into the forest for two weeks every month!” What his parents didn’t know then was that their son had fallen under the hypnotic spell of arguably the most mesmerising animal on the planet. One night, sitting besides a campfire in Ranthambore, Thapar heard the fear-stricken calls of deer and other wildlife signalling the presence of the amber-eyed predator nearby. The split second in which he caught a fleeting glimpse of the tiger rustling through the grass forged an irrevocable bond between man and beast. “I felt connected… as if this was the unknown that I was seeking all my life,” says Thapar, the awe of that moment still echoing in his voice.

Soon, the spartan rest house in Ranthambore became Thapar’s second home. His jeep became a permanent fixture in the reserve’s deciduous forests and grassland. He spent long backbreaking hours studying pug marks, observing and making notes on tiger behaviour, and analysing predator-prey equations. As he started following the tail of the tiger, he phased out filmmaking and turned to writing. Over the years, he has written 14 books on the tiger and also hosted BBC’s famous television series Land of the Tiger, which earned him worldwide recognition. His books lovingly document his experiences with the magnificent animal that for centuries has been an icon of virility and power throughout Asia. Thapar remembers nights when he along with his ‘tiger guru’ Fateh Singh Rathore, then park director of Ranthambore, walked the jungles with jingling cowbells to entice the nocturnal creature out of the shadows. When asked if he has been in any potentially life-threatening situations with the tiger, he retorts, “I find crossing the busy Ashram Road in Delhi far more dangerous than walking in the jungles with the tiger.”

In the 1980s, with the hunting ban in place, tiger sightings became more common. “I used to come across as many as 16 tigers a day,” says Thapar. His eyes light up as he talks about Genghis, a male tiger, who disliked being watched while he ate, and Nasty, a tigress, who hid in the grass and issued a rip-roaring mock growl every time a jeep passed by. The object of his affection was elusive through much of the 1970s, though. Thapar had to wait five years before he saw a tiger at the watering hole in Ranthambore in 1981. The animal had every reason to be wary — rampant poaching and encroachment of its habitat made it shun the company of man. There were many villages within the forests that depended on forest produce and wildlife for sustenance. After realising that one of the chief threats to the survival of the tiger was human invasion of the reserves, Thapar struggled to convince villagers to relocate to the outer periphery.

“In a country where 25 million people are added to the population each year, land is the most precious commodity. And where does this land come from?” thunders Thapar. “Naturally everybody feels it’s alright to squeeze out the forest land. No one stops to think about the unborn child of India. Where is he going to get water from? More than 600 rivers and perennial streams flow out of the tigers’ forests. If we do nothing to protect the forests, 100 million people are going to suffer from lack of water.”

Thapar is aghast that a country that is endowed with forest value worth up to $ 2 trillion is so indifferent to preserving its natural wealth. We are losing more than 10,000 sq km — roughly worth $ 12 billion of dense forests — to the timber and land mafia every year. “In India, nature is like a bank with no guards outside to protect it. Over the years, our political leadership and inept bureaucracy have allowed such exploitation of our natural treasury that everybody has gone away with their pockets filled.” He minces no words when he says that the policies — which offer business interests the freedom to plunder the forests at will — are as much to blame as the timber mafia or poachers. “It is ironic that Indian tycoons fly their personal jets to Africa to enjoy a vacation in Masai Mara, but feel no corporate responsibility towards preserving the wildlife in their own homeland.”

In an effort to keep human habitation inside the forest at bay, he started the Ranthambore Foundation in 1987. The foundation launched many welfare initiatives to improve the lives of the villagers: a women’s cooperative to generate income through local handicrafts; free immunisation programmes; family planning drive; literacy programmes; and a pilot project to grow fodder for cattle to reduce grazing inside the park. Biogas generators were also set up to produce gas from cattle dung, so villagers needn’t risk foraging for firewood in tiger turf. “I had the idealistic hope that I could work with local people to save the tiger,” says Thapar with a sigh. Today, he is bereft of that idealism after discovering the strength of the government’s monopoly over the forests and disillusioned by forest dwellers who collude with the timber mafia to get a higher foothold on the economic ladder.

Thapar concluded his role in Ranthambore Foundation in 2000. Earlier, in 1992, when Ranthambore was in the eye of a poaching crisis, he was forced into the terrain of government decision-making when then minister for environment and forests Kamal Nath inducted him into the steering committee of Project Tiger, a wildlife conservation project initiated in 1972 by former prime minister Indira Gandhi, who was a passionate wildlife and environment enthusiast.

Part of the blame, he believes, is also because forest guards in India are vastly unequipped. As poachers stalk through the wilds, Thapar feels it is imperative that government empowers guards with more than just a bamboo staff. He points to the Masai Mara wildlife reserve in Kenya — an exemplary model for wildlife reserves around the world that earns Rs 24 billion a year as gate fee alone — where forest guards have shoot-at-sight orders when they confront a poacher. He still remembers vividly the night in 2000, when he drove to Khaga in Uttar Pradesh, where border police had seized wildlife contraband heading to China through Nepal. “There were 546 leopard skins and 40 tiger skins wrapped in New Delhi newspapers,” growls Thapar. That night when he hit the bed, tough-as-nails Thapar couldn’t stop the tears from flowing. His passion for the animal runs deep. As P K Sen, executive director of Ranthambore Foundation, describes it, “I have yet to meet a man who is more obsessed with the tiger. Valmik lives, breathes, thinks… the tiger.”

When Thapar sounded the warning alarm on the current tiger crisis two years ago, most state governments chose to defend fudged tiger counts to save their pride. “Despite the Sariska tragedy we have not learnt our lesson,” he rues. “Today there are only three male tigers in the Panna Wildlife Reserve in Madhya Pradesh, but the state government insists there are 23!” Sen admires Thapar’s fearless nature. “He is completely unafraid of expressing his fiery views regardless of the power and position of the person he is talking to.”

It’s impossible to sit with Thapar and not be singed by the passion he feels for his cause. “Valmik, with his sheer intensity, is truly the uncompromising voice of the tiger,” says close friend and renowned wildlife researcher Ullas Karanth. “As a science-based tiger conservationist, I find him a bit too impulsive in his actions. He could accomplish even more for the tigers he cares so deeply about if only he could be a bit more reflective.”

The vitriol Thapar spews at the administration is not borne out of raging idealism alone; he is frustrated with the lack of action being taken despite the perilous situation that we are in. In 1994, he had submitted a report to the government in which he had suggested establishing a Wildlife Crime Bureau. After extended hemming and hawing, the bureau was set up in 2007, but no one has been hired to lead it yet. “In India, wildlife trade is the second largest illegal trade after narcotics and yet we have found no one to man the Wildlife Crime Bureau. Is there any excuse for such lethargy and idiocy?” While I write this, there is a tannery in Khaga that is curing and tanning leopard skins, right opposite a police station; a restaurant in China serving tiger bone soup; and a bottle of tiger bone pills being sold for Rs 1 million in Japan. Most of them, of course, derived from tigers smuggled from India.

As we talk, Thapar’s five year-old son Hamir — named after a 13th century Rajput king of Ranthambore — peeps in through the glass door trying to seek his attention. As father and son share a smile, I can see the fire in those blazing eyes softening to a warm glow. I ask Thapar how it feels to be a father so late in life — he became a father at 50. He smiles. “Physically it’s very demanding keeping pace with such a young child. But at the same time, I am learning so much at this age.” As Hamir loves swimming, Thapar has now learned to snorkel so they can explore underwater reefs together. Thapar is married to Sanjna Kapoor, 40, daughter of actor Shashi Kapoor and director of Prithvi Theatre, Mumbai. They met when she interviewed him on the television show Amul India Show in 1998, around the same time he had won acclaim for hosting the BBC television series, Land of the Tiger.

A kin to the jungle cat protecting its cubs, Thapar is fiercely protective of his personal life. I have been tersely warned well in advance to keep out intrusive personal questions. Yet, this is the closest I’ll ever get to provoking a tiger, so I venture anyway. How has life changed after marrying so late? He mulls over the question for a moment and then answers softly, “I am known to be the rudest guy who walked this earth. Probably if marriage and fatherhood hadn’t happened when it did, I would have been more reclusive and more abrasive…. Fatherhood, particularly, mellows you down.” Watching Hamir grow up brings him the same joy he felt watching a young cub grow into a tiger. He admits he no longer has the freedom to disappear in the jungles whenever he desires, but he is happy to plan his expeditions around Hamir’s school vacation. “I think I am lucky. Tell me how many people get to discover fatherhood at 50?”

There are more firsts to come. Thapar plans to collaborate with an art historian on a book that explores the symbolism of tiger in Indian art. By the end of this year, he will be in UK as part of the jury of the Wildscreen Festival, the world’s largest festival on wildlife and environmental films. Today, he sees himself as a semi-retired campaigner keen to talk to young people who are contemplating a career in wildlife. He urges the younger generation to take up a more active role in protecting the wildlife — “Today’s youth do not want to get their feet dirty in the jungles; they are far too busy escaping to foreign universities.”

As the interview comes to an end and we enter his study for a brief — and for him, reluctant — photo-shoot I realise that the tiger indeed follows Thapar everywhere. The shelves are lined with countless books on wildlife; the rugs have tiger motifs; and black-and-white photographs of tigers adorn the bookshelf. I fire one last question at the tiger man: if he had another chance to do it all over again, would he still do so knowing that there may be no light at the end of the tunnel? “If I had a chance to see the tigers that I did,” he says, “and walk the same jungles that the magnificent beasts did, I would do it again and again — and again.”

Photo: Valmik Thapar Featured in Harmony – Celebrate Age Magazine April 2008

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….