People

Two months ago, Pandit Jasraj sang to packed houses in New Jersey. In October, he mesmerised audiences in San Francisco. Now he is on his way to perform in New York, and then again in New Jersey. Clearly, the world can’t get enough of his voice, which is only growing richer with time. Rajashree Balaram meets the 79 year-old Hindustani classical maestro who thinks music is just another word for prayer

First things first. Pandit Jasraj is allergic to perfume. As we walk into his four-bedroom flat in Versova in suburban Mumbai on a rainy September morning, he greets us abruptly: “Keep your distance if you are wearing perfume. It affects my voice.” The instruction would have sounded terse coming from anyone else. But uttered by Panditji — seated at his dining table, wearing a short-sleeved white muslin kurta, his eyes sleep-deprived and his fuzzy white hair casting a disheveled halo — it sounds anything but curt, especially when he flashes his roguish smile. His voice is gentle even as he admonishes his young household help when she hurriedly takes away his cup of unfinished coffee. Minutes later, he thanks her profusely when she warms up his third large cuppa. He throws a minor tantrum when we ask him to change into formal clothes for photographs. And later indulges us by changing into not one, but three outfits for an elaborate photoshoot on his terrace through an insistent drizzle.

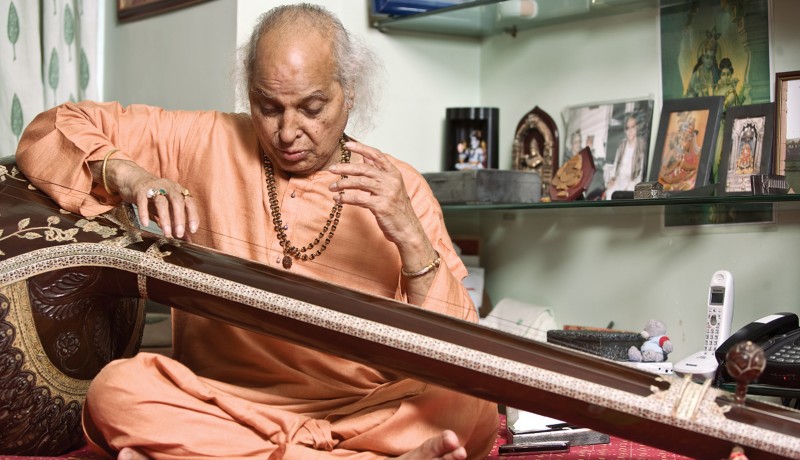

The contradictions in his demeanour are enchanting, but what holds you spellbound is his voice. As he does his riyaaz (practice) in his bedroom, strumming on the tanpura gifted to him by his father-in-law, filmmaker V Shantaram, you feel strangely privileged, almost grateful, to be standing in close proximity to this voice, one renowned for its ability to rise and fall effortlessly over all three-and-a-half octaves. The reverberations fill the room and you begin to understand why the world puts the man on a pedestal — Padmabhushan, Padmavibhusan and Sangeet Natak Akademi plaque on his walls; a scholarship instituted in his name by the University of Toronto; an auditorium in New York named after him; and the venerable title of Sangeet Martand (musical wizard) among many, many others.

Panditji wears the accolades like a cherished cloak around him. At 79, he is still discovering new facets to his voice. Last year, he made his foray into Hindi cinema with director Vikram Bhatt’s horror flick 1920, for which he sang for the promotional video. “It was a fresh, exciting experience,” he says. Indeed, his zest for life is touching and his views on music and musicians passionate. Both leave an impact that’s as indelible as his voice.

IN HIS WORDS

The first time I realised that I wanted to become a singer was when I heard Begum Akhtar. There was a small tea shop where they played Begum’s songs on the gramophone, very close to our house in Pili Mandori, a small village in Haryana. “Deewana banana ho to deewana bana de, varna kahin taqdeer tamasha na bana de”. I was so enamoured with Begum that I used to often skip school and loiter around the shop to hear her. It was her marvellous voice that first introduced me to the full force and power of music. I knew then, almost instinctively, that that is what I wanted to do with the rest of my life: sing. Years later, when Begum attended my performance in Pune, I was trembling with trepidation. When I finished, she walked over to me and said “If I had been younger, I would have loved to learn singing from you.” Life couldn’t have been more benevolent to me.

Everything I am today, I owe to my brother Pandit Maniram, who was my guru. My father Pandit Motiram, who was designated as the state musician by the last Nizam of Hyderabad, died when I was four. My brother trained me. We are the fourth generation of singers from the Mewati gharana that has its origins in Mewat in Rajasthan. My brother and I often performed for royalty. The Maharaja of Sanand in Gujarat, Jaywant Singh Waghela, was an ardent connoisseur of music and one of our chief patrons. In fact, I have learnt a lot about the intricacies of music from Jaywant Singhji.

I used to accompany my brother on concerts as a tabla artist. Later I gravitated to singing. I remember waking up at daybreak and putting in 14 hours of riyaaz every day. My passion for music also has a lot to do with where I come from. People rarely associate Haryana with art and culture but I would like to tell you that the state has 42 villages named after raga.

I have been a music teacher for a large part of my life. In 1947, after Independence, when a lot of princely states merged, it was difficult to sustain royal patronage. In the resulting upheaval my brother and I moved to Kolkata. My brother set up a small school, Sangeet Shyamala, where I was appointed music teacher. Sometimes I used to get a few assignments with All India Radio for which I was paid Rs 40. My first public performance was at a musical conference in Nepal. I was 22 years old. I was part of a large delegation from India comprising dancers and instrumental artists. The conference cemented my status as a classical vocalist. The king of Nepal, Tribhuvan Vikram, felicitated me after my performance.

Some of the most humbling moments of my life were also the proudest. In 1963, I sang at the Radio Sangeet Sammelan, a musical conference that was a luminous gathering of the best talent from India and Pakistan. When I was singing on stage, the great Pandit Omkarnath Thakur, as was his habit, was prowling in the audience. It was a bit unnerving for me. After I had sung for about an hour, he came up stage and hugged me. His booming “Shabbash” still rings in my ears.

The best compliment I have received in my life was from Pandit Bhimsen Joshi. He once told me, “Jasraj, when I look behind and see you following me I feel immensely happy and at peace.” To me, he is the greatest singer that we have today. Apart from him, I have always admired Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Ali Akbar Khan and Pandit Omkarnath Thakur. I consider myself fortunate that I had the opportunity to listen to their voices and be part of the same era. Another singer I admire is Lata Mangeshkar. Once while taking a nap in the afternoon, I woke up with tears streaming down my cheeks. When I heard the song playing on the radio, I finally figured out the reason behind my intense emotional reaction — Lataji was singing Prabhu tero naam….

The great M S Subbalakshmi [Carnatic vocalist] once said, “God resides in Jasraj’s voice.” That compliment will always stay close to my heart. I associate everything that is holy and divine with singing. It goes back to the time when I was 14 and my brother had lost his voice briefly. Maharaja Jaywant Singh Waghela had invited us over to his estate in Sanand. When he realised that my brother could not sing, he took us to the Kali temple in his palace. He went inside the sanctum sanctorum and shut the door. After some time, he came out and told us that my brother would be able to sing only if he sang for the gods. That night, my brother sang from 12 midnight to six in the morning. After that episode, I have been a lifelong bhakt (devotee) of Kali. Music is my prayer. If I do not invoke the gods, how will I be able to say my prayers?

Music is the only thing on earth that is truly secular. It does not speak any one language and yet breaks all barriers. When I perform on stage, I may be accompanied by a Muslim on the tabla, a Sikh on the tanpura and a Brahmin playing the harmonium. But for those few moments while we are performing together on stage, we are not known for our caste or community but only the music we create. We praise, criticise and encourage each other without bias. Every religion employs music to communicate to the Almighty — whether it is Sufi strains or Christian hymns. There is a rhythm to our ethnic identity that we fail to recognize and respect. Finally it all emanates from the same source: the One up there.

Music is a blessing that does not merely begin and end with one’s voice or instrument — it is a way of life. In 1977, I spent a few days at Ali Akbar Khan’s house in New York. Those days were suffused with music. Khansahib’s students used to come over and there would be music all night long. When I woke up in the mornings, I’d find Khansahib washing the dishes, left in the sink by his students. When I offered to help, he would turn me down. I used to be a bit annoyed at his students for being so thoughtless and impolite. But Khansahib would shrug off my concern and say that he enjoyed the musical banter too much to be upset by the menial task that followed it. I realised he had risen above the constraints of ego and fame and had gained the greatest virtue of all: a touching humility that was immensely inspiring.

I follow the guru shishya parampara with my disciples. They live with me and learn from me. I do not charge a paisa for the tuition. Neither personally, nor through my music schools in Pittsburgh, Tampa and New Jersey in the US. All three schools are managed by my disciple Pandita Tripta Mukerjee. I look out for purity and honesty in a person’s voice. If it reaches out to me, I am prepared to devote my time and energy to teach that person. In the process, I end up learning a lot from my disciples. Once, Ankita, a little girl who had travelled all the way from Nanded to attend my concert, came backstage and told me to teach her how to sing. I was amused at her audacity. She simply said, “When I heard you sing, I knew that you would be the person to teach me to sing.” Her confidence and ability to make her own destiny shook me. Ankita has lived at my house for the past few years, like many disciples before her.

I get annoyed when people ask me about the level of commitment of today’s young generation. It’s almost as if the interviewer expects me to deride them for being frivolous. I think the generation today is intensely committed and passionate about their calling. Today, youngsters have better tools at their disposal. For instance, my brother used to spend long hours teaching me a raga, and I would barely manage to remember 40 per cent of that the next day. Today, my disciples have an iPod that records what I am teaching them. They then go over it again and again through the day and the next day when I meet them, they have mastered it to a greater degree of perfection than I could have at their age. But how can I begrudge them the technological advances that they are surrounded with? As long as technology helps them become better artists, I have no complaints.

I feel sad that we take our musical gifts so lightly. At my music schools in the US, I have many students who are foreigners. Though they are all devoted to Indian music, I have observed that they are unable to pitch their voice through all seven sur the way we Indians do — the Africans do it beautifully though. I hope we learn to respect the abundant talent we have in our country. And I am not just referring to budding talent. There are many old singers and musicians who are ignored by the government and struggle to make ends meet. I am trying to reach out to them through the Indian Music Academy that my daughter Durga and I launched in 2006. We have set up scholarships for needy talented youngsters from small towns, and are also trying to help out senior musicians. But I strongly urge the government to set up a pension for senior musicians who may not get a regular income anymore.

Earlier, like all parents, I too felt that my children should have taken my legacy forward. But today I am immensely proud of what they have achieved. When they were little we used to sit and sing together. Durga would play the tanpura and Sharang would be on the tabla. Today, Sharang is a respected music composer in his own right and Durga runs a music company that encourages Indian classical music. Durga uses my surname while Sharang prefers to be known as just Sharang Dev. I don’t respect one more than the other for the choices they have made. I am proud that my daughter cherishes her father’s name, just as I am proud that my son cherishes his individuality. As parents, we rarely realise that for all our unconditional love, sometimes we unfairly expect our children to mirror our lives, our likes, dislikes and lifestyle. I have learnt to accept my children for what they are. Acceptance comes with wisdom and wisdom comes with time.

Every relationship deepens and strengthens over the years. Even my marriage has had its share of friction like most. Madura and I have survived through controversies and ups and downs. Of course, we have had our share of fights. We both have a nasty temper. But I admire her for standing up for what she believes in. She is no doormat.

Music acted as a catalyst to our attraction. I met Madura in 1954 when I had come from Kolkata to Mumbai for a concert. She is a trained classical singer, so she always appreciated the finer nuances of music. She would come backstage at my concerts and praise me. I still remember the way she would twirl a lock of hair between her fingers — in the charming way that women have — as she spoke to me. I could not muster the nerve to propose to her as she came from such an illustrious background. I was still struggling to make ends meet as a singer at All India Radio and coaching students in Kolkata. Despite her reserved demeanour, she was the one who told her father about me and made the first move. Madura has amazing perseverance and courage. Even today, she is busy doing her own thing and has a mind of our own. Now, she is directing a Marathi film — she has not slowed down at all.

The process of ageing is challenging; it does not have to be boring. Why do we let age leach all colour from our lives? For instance, I have always loved wearing silks when I perform and continue to do so. I love the richness and purity that it exudes. And I feel we are influenced by what we wear. I like bright colours — mustard yellow, red and cerulean blue. I don’t think there are too many musicians of my age who wear such flamboyant attire for their performance. I also appreciate beauty in all its forms, whether it is a beautiful flower, a painting or a lovely woman — don’t let Madura hear that! Seriously, we need to find a way to rejuvenate ourselves. It could be anything that makes us happy. It’s either that or we shrivel up inside. I enjoy playing with the children in my building whenever I get the chance. I let go of all inhibitions and simply set the child in me free.

I take brisk walks across the length of my house from one room to another. My daughter Durga often joins me on these walks. It’s good fun because we keep sparring and exchanging witty repartee on the way. I cannot stick to a fixed exercise regimen because of all the travelling that I do. When it comes to food, I avoid onions, garlic and oily food. Though I have no blood pressure or sugar complaints, my diet is strictly dictated by the rigours of singing.

I love everything that keeps the past alive. I enjoy watching movies like Veer Zaara and Jodha Akbar that showcase the subtlety and delicacy of a bygone era. I don’t go to the theatres anymore. I just rent a DVD; sometimes of course, I end up sleeping in the middle of the movie [chuckles].

I cannot deny the little aches and pains of growing age. Sometimes I cannot hold my breath for as long as I could earlier, though I can still put up a marathon performance for six hours. When I do my riyaaz, I have the habit of laying out a sequence of playing cards before me. If I hit a point where I am unable to get my sur right, I keep changing the order of the cards and continue singing, and somehow, strangely, I manage to overcome the difficult spell. I know it’s eccentric. But what’s life if we do not have our little mysteries?

Photo: Kerry Monteen Featured in Harmony – Celebrate Age Magazine November 2009

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….