People

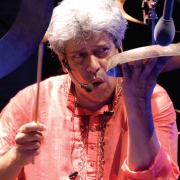

At a time when Indian classical music was considered sacrosanct, he stepped out of its confines to create his own music. Over the past five decades, virtuoso percussionist Trilok Gurtu has created his own niche in world music through his eclectic approach. Today, as the maestro continues to play his timeless music, he shares his transcendental experience with Sai Prabha Kamath

His nimble fingers can create magical soundscapes on any kind of surface; he calls it “soulful sound designing”. For internationally renowned master percussionist Trilok Gurtu, musical instruments and mundane objects alike are a source of rhythm and joy. Indeed, his one-of-a-kind percussion kit—encompassing tabla, drums, snare, gong, djembe, metal wires, ghungroo, and even a bucket filled with water—is a true reflection of his personality: innovative and unconventional. Gurtu views music as an expression without boundaries. “For the body, we need food; for the mind, we need thoughts; and for the soul, we need music… music without barriers,” he says. As a result, his music transcends style and genre—jazz, rock, pop, Indian classical.

Born in 1951 into a musical family in Mumbai, where his mother Shobha Gurtu was a legendary Hindustani classical vocalist, Trilok had a natural instinct towards rhythms and tunes. Though he was adept at playing the tabla, he refused to play to the gallery and charted a distinct path for himself. At a time when ‘world music’ was an unknown term, this self-taught artist’s bold experimentations—crossing genres—were considered avant-garde and, naturally, not accepted by purists. “If there are parents in the same field, it is easy for children to establish themselves. But I chose the difficult path. Though my mother supported me, she also warned me that my journey wouldn’t be easy,” he recalls.

As he didn’t find any takers for his kind of music in India, he crossed borders in search of an audience and, over time, found Europe the most receptive. After his share of struggle and study of music, he teamed up with great musicians such as Joe Zawinul, Jan Garbarek, Don Cherry, Bill Evans, Pharoah Sanders, L Shankar, Dave Holland and John McLaughlin, creating an enchanting musical amalgamation of the east and the west. The Germany-based percussionist has also collaborated with legends of Indian classical music such as Ustad Zakir Hussain, Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia, Zarin Daruwala and Pandit Ram Narayan as well as popular singer-composer Shankar Mahadevan.

This summer, from April to June, he finished a packed schedule at music festivals across Europe and is now headed for a well-deserved vacation. We met Gurtu some time ago at his family home in Worli, Mumbai, during his annual visit to India. Joining us for a short while was his elder brother Narendra, who manages his India tours. “All of us are musicians. However, someone had to run our family business and my brother was assigned that task,” says Trilok. Dressed casually in loose cottons, he candidly spoke at length about his inspirations, struggles, experiments and learnings. Excerpts from an interview:

Art runs in your family. Your grandfather was a musicologist and sitar player and grandmother a dancer; your mother was the queen of thumri and had sung in Hindi and Marathi, including for films. Your late brother Ravi made a name for himself as a percussionist in Bollywood. How did they influence you musically?

I am indeed blessed to have had these people around me. I had my first brush with tabla from my mother’s lap and started playing it when I was four. She used to allow me to just play. As a young kid, I would play beats on our dining table. My father used to encourage me by giving mangoes as incentive!

What were the learnings from your mother?

I was the youngest kid after my brothers Ravi and Narendra and used to be extremely mischievous. But she used to be very patient with me; she was a simple, saintly person. I received fantastic musical training from her; as a child, I used to accompany her during her musical concerts. I imbibed the art of listening from her. Once there was an urgent need for an accompanist for her vocal rendition as the tabla player fell sick. I was requested to fill the gap. I was only too happy to lap up the opportunity. Over time, I started playing for her regularly.

Did you consider pursuing vocal music like your mother?

Well…she was too great for me to try that. I always felt I could not match up to her!

When did you receive formal training in tabla?

I started training in tabla formally when I was 11 from guru Manikrao Popatkar from the Benaras gharana and then from versatile dholak player Abdul Karim Khan saab. I have also trained under tabla exponents Ahmed Jan Thirakwa Khan saab and Pandit Suresh Talwalkar saab.

What inspired you to explore a plethora of percussion instruments later?

From a young age, whenever I saw a percussion instrument, I couldn’t contain my excitement. I used to be hungry all the time to play them. When I was about 13, I used to play bongo for [versatile singer] Mahendra Kapoor’s troupe and travel with him. A great influence was my late elder brother Ravi, known as the ‘king of bongo’ and one of the most sought-after percussionists of Bollywood in the 1970s. He introduced me to percussion instruments from all over the world. I used to be his arranger and prompter during programmes and thus imbibed a lot through listening. Both of us used to play at events too.

We heard you were a table-tennis champion in your college days….

Yes, I did a bachelor of arts from Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Mumbai, but never actually attended classes. I played cricket, table tennis and excelled in sports. In table tennis, I used to beat even seeded players and was considered for National level. Thank god I was not selected as I was overage! Else, I would have been a sportsperson today.

You started playing instruments in Western genres such as jazz and rock. Did you receive training in them?

Thanks to my exposure to Carnatic music, I picked up Western classical genres such as jazz and pop on my own. I used to listen to Carnatic music maestros such as Palghat Mani Iyer, Subramaniam Pillai, M L Vasanthakumari and Palghat Raghu, and it helped. Interestingly, I found African music close to Carnatic music; there is a Dravidian connect.

How was the response when you started playing western music?

When I started playing the drums, no one liked it; many couldn’t accept the fact that a local man could play a Western instrument and they even called me names. I was hurt. But owing to my parents’ encouragement, I continued my passion. My friend Jack, a drummer himself, recognised my potential. We used to carry instruments on a handcart around Mumbai to play at programmes. However, the response we received was uninspiring to say the least and I could see no future here for my kind of music.

You joined a music band called Waterfront when you were 18. Could you share some experiences?

In 1969, I joined the band with musicians Soli Dastur, Adil Batliwalla, Roger Dragonette and Derek Julien. Soli used to write original songs and we used to perform at nightclubs and discotheques. But no one understood the music we played and there were no opportunities here. Our future looked bleak. So our band took off on a Europe tour. We toured places such as Germany, Italy, Switzerland and France. However, there were few takers there, too, for our kind of music. We struggled a lot and even had to go hungry for days as we were broke eventually. We then started busking [playing music on the street for voluntary donations]; with no percussion instrument, I played on plates, vessels and whatever I could lay my hands on. This was a period when table was unheard of there. This was the most difficult but the best time of my life as it made me a true percussionist. No one at home knew about our struggle. Our troupe finally got disbanded; all of them returned to India but I chose to stay back in Italy, where I learnt to play jazz, free jazz and rock by the sheer power of listening. Later, when I returned to Mumbai, I had a stint as a percussionist with Bollywood music composers S D Burman and R D Burman’s orchestra.

We learnt that you were refused admission to the Berklee College of Music in the US in 1970s. Were you dejected?

I tried to get admission there to learn music arrangement. But the dean of the college was not impressed with me; the artists I played with were unknown to him. Also, he had no idea about African music, which I was familiar with. I just left the place saying, “I will come back with my own music and my own way of playing.” With that, I stopped playing in America. Over time, I went on to win American magazine DownBeat’s Critics Poll for Best Percussionist seven times. Looking back, the rejection was a blessing in disguise as it made me understand my country and our culture better. In 1976, I was invited to play in Munich, Germany. I went there and studied music, including African, Brazilian and Indian (south), very deeply.

American jazz trumpeter Don Cherry was your mentor who introduced you to world fusion music. Was it a turning point in your life?

Yes, meeting Don Cherry in Italy in 1974 was indeed a turning point. His rhythms and analysing skill of orchestra music were amazing. However, he was an underrated artist. With him, I started analysing every kind of music and got to learn Bulgarian folk music; I also started appreciating the amazing mathematics applied in playing percussion instruments such as thavil and mridangam. In 2013, I released an album, Spellbound, as a tribute to my dear friend, featuring his favourite instrument—the trumpet.

You have collaborated with top musicians from all over the world. Please share a few key highlights from your incredible career.

Performing for American jazz and world music group Oregon, formed by Ralph Towner, Paul McCandless, Glen Moore and Collin Walcott, was one the highlights of my career. When Walcott was killed in a car accident in 1984, I was invited to replace him as a percussionist. We did three albums—Ecotopia, 45th Parallel and Always, Never and Forever—together. The other high point was being part of the quartet that veteran violinist L Shankar led with jazz saxophonist Jan Garbarek and tabla maestro Zakir Hussain; playing as a featured soloist in the John McLaughlin Trio [of Mahavishnu Orchestra]; collaborating with electronic music wizard Robert Miles; and playing for NDR Bigband – The Hamburg Radio Jazz Orchestra. Playing my own music was another milestone in my career.

In the 1980s, you collaborated with your mother for group concerts; she was a vocalist in your fusion album Usfret. Being a Hindustani classical musician, did she have any reservations about fusion music? Did it require a lot of convincing on your part?

I have always had the thirst to do something new, something different. When I invited my mother to be a guest vocalist in our group concerts, she was immediately game. She was an incredible person: jovial, innocent, pure-hearted, humble. She was the most energetic member of our group, ever ready to sing. Every rendition of hers used to be new and different. During our performance in Italy, she used to get a standing ovation even before the programme commenced. At a time when the term ‘world music’ didn’t exist, I did Usfret, a collaborative album with my mother, Don Cherry, [guitarist] Ralph Towner, [violinist] L Shankar, [bassist] Jonas Helborg—a trailblazer that was far ahead of its time.

You innovate, improvise and create music from unconventional things like bells and buckets. What inspires you and how would you describe your renditions?

Soulful sound designing is how I would like to describe my compositions. It is an idea; as a child, I used to create sounds from the peep [household drum] in which we stored water. I do the same thing now—create sounds and rhythms from various instruments and objects. For this, you have to be alert to the sounds around you.

Can you describe the transitions you make while playing different instruments?

It’s a natural soul process. When I am playing, I forget that I am in this world; I am with my Sadguru Sri Ranjit Maharaj and it is a transcendental experience.

What’s the greatest compliment you have ever received?

Carnatic music has always had a major influence on my performances. Western audiences love it when I play rhythmic pieces such as thillana. In 1982, the master of mridangam Palghat Raghuji heard me playing at the Jazz Yatra festival in Mumbai and called for me. Meeting him was a thrilling experience and dream come true. During our meeting, he said, “You are our real cultural ambassador abroad.” That is the best compliment I have ever received.

A moment you cherish….

During one of my musical tours as a struggling artist, our band was stranded at Old Delhi railway station, penniless. The coolies helped us; they served us warm tea and kachori when we were hungry and gave us a place to sleep. Later, their joy knew no bounds when we got a job at The Oberoi and invited them to attend our concert. This is a moment I treasure.

What keeps you busy?

I used to perform 300 days a year. Now I have become more selective in choosing orchestras, bands and solo performances. Today, I compose music for orchestras, apart from playing solos. Also, I will be doing a German movie soon.

What is music to you today?

For the body, we need food; for the mind, we need thoughts; and for the soul, we need music… music without barriers. I have done crazy stuff like combining African music with Indian veena and Bulgarian kaval for a rock performance. Music needs to have a spiritual element to it. The music that I am doing today is for atmagyaan [self-knowledge]. However, if I can make the listener’s mind happy and positive, nothing like it.

Do you think we need more musical education in our schools—both theoretical and practical? What steps can be taken in this regard?

Our schools should give children the right guidance for all kinds and genres of music, not just classical. Additionally, we need to empower our children to pursue music of their choice and interest.

What are the changing trends and challenges in the music industry, specifically India?

I am not much aware of the scene in India. But one contrasting trend: In India, while musical shows attract sponsors, abroad the performer needs to attract audiences. One encouraging trend is that reality shows today are giving a good platform to performers. However, the question is: What after the show?

With media playing a significant role in audience reach, is it an exciting time for instrumentalists?

Yes, definitely, that too at a time when record companies are not forthcoming. However, technology should not be misused.

What are your thoughts about e-learning?

Like Ekalavya in Mahabharata, if there is dedication, one can learn from anywhere. But it is always better to learn music one-on-one.

Your best performance?

It is egoistic to say ‘I perform’. I am never happy with my performances.

What are your other interests?

Cooking and wine tasting. I learnt cooking from my mother and, now, I cook international and mixed cuisine. I am a connoisseur of wines and have been invited for wine tasting by countries such as Italy, France, Germany and Austria. I have thousands of wines in my cellar and my wife is tired of my expensive hobby!

How do you keep yourself fit?

I go for 45-minute walks twice—morning and afternoon—a day.

Please share something about your family.

I met my wife Ute at a concert in Hamburg and she is the best thing to happen to me. We courted for 15 years before getting married and we have been together for 40 years now. Our only daughter Manini has completed her master’s in economical psychology and works in Barcelona, Spain.

What is your message for our silvers?

Though I am 67, I don’t feel old. I would advise all my fellow silvers to take care of their health. Don’t abuse your body. You can achieve anything if you are healthy and fit.

AWARDS AND NOMINATIONS

- Best Overall Percussionist – Drum magazine (1999)

- Best Overall Percussionist – Carlton Television’s Multicultural Music Awards (2001)

- Best Percussionist – DownBeat magazine Critics Poll (1994, 1995, 1996, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002)

- Best Asia/Pacific Artist Nominee – BBC Radio 3 World in 2002, 2003 and 2004

DISCOGRAPHY (SOLO AND COLLABORATION)

- 1974: La Terra (The Earth) – LP with Aktuala (Bla Bla, 1974)

- 1976: Tappeto Volante (Flying Carpet) – LP with Aktuala (Bla Bla, 1976)

- 1977: Apo Calypso – with Embryo

- 1979: Friends – with Toto Blanke Electric Circus

- 1980: Family – with Toto Blanke Electric Circus

- 1982: Personal Note – Mark Nauseef with Joachim Kühn, Jan Akkerman, Detlev Beier

- 1983: Finale – with Charly Antolini

- 1985: Song for Everyone – with L Shankar

- 1987: Usfret

- 1987: Ecotopia – with Oregon

- 1989: 45th Parallel – with Oregon

- 1990: Live at the Royal Festival Hall – with the John McLaughlin Trio

- 1990: Living Magic

- 1991: Always, Never and Forever – with Oregon

- 1992: Que Alegria – with the John McLaughlin Trio

- 1993: Crazy Saints

- 1995: Believe

- 1995: Bad Habits Die Hard

- 1997: The Glimpse

- 1998: Kathak

- 1998: Cor – with Maria João & Mário Laginha

- 2000: African Fantasy

- 2001: The Beat of Love

- 2002: Remembrance

- 2004: Miles Gurtu – with Robert Miles

- 2004: Broken Rhythms

- 2006: Farakala

- 2007: Arkeology

- 2009: Massical

- 2010: Piano Car – with Stefano Ianne

- 2011: 21 Spices – with Simon Phillips + NDR Bigband (Conducted by Jorg Achim Keller)

- 2013: Spellbound

Photographs courtesy: Trilok Gurtu Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine July 2018

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….