Columns

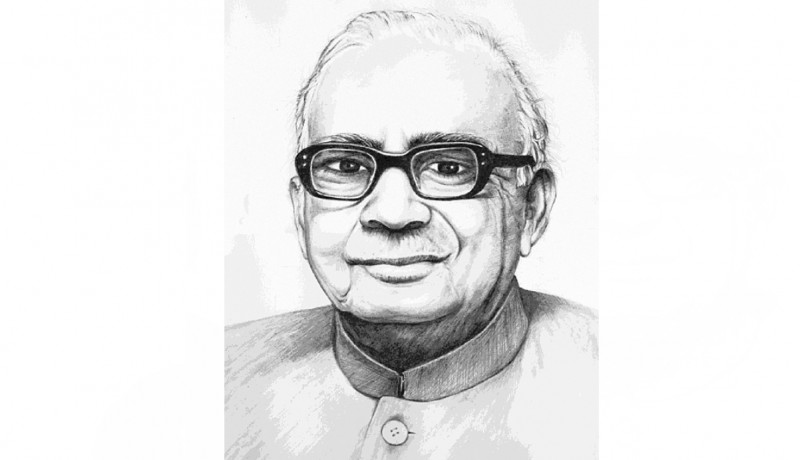

K D Malaviya singlehandedly took up the cudgels against the combined might of multinational oil cartels and their supporters in India to establish ONGC, writes Raj Kanwar.

Keshava Deva Malaviya’s life has two distinct but fascinating chapters. The first chapter that began in 1929 was almost entirely devoted to the freedom struggle. He had by then obtained a degree in vegetable oil technology from Kanpur’s famed Harcourt Butler Institute of Technology and could have got a cushy job. Instead he plunged head on in the freedom movement. Between 1929 and 1942, Malaviya went to jail on nine different occasions. Jawaharlal Nehru was his fellow inmate during one of his incarcerations; their relationship was to play a historic role in the years to come in the creation of a national oil industry in the country.

The second chapter that began in 1952 with his election to the first Lok Sabha turned out to be epoch-making. Nehru had made him a deputy minister in the Ministry of Natural Resources & Scientific Research headed by Maulana Abdul Kalam Azad. Ironically, his portfolio of Natural Resources did not include either oil or the Council of Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR). It was possibly intended to be a rebuff to Malaviya. The then director-general of CSIR, Shanti Swaroop Bhatnagar, had sway over the world of science and technology in India that was all-pervasive. He was in favour of permitting multinationals to prospect for oil and gas in India. Multinational companies such as Standard Oil Company (Stanvac) and Burmah Shell waited in the wings hoping to jump at any opportunity. Bhatnagar had almost decided to give a prospecting license to Stanvac in Jaisalmer, Rajasthan, and a proposal to that effect had already been put up for Nehru’s approval. Prospecting rights in Bengal and Assam had already gone to Burmah Shell that had been operating there for decades. To cut the long story short, Malaviya with Nehru’s help managed to overcome all these formidable hurdles and finally laid the foundation for the formation of a national oil company. Thus, Oil & Natural Gas Commission (ONGC) made a modest beginning in 1956. Malaviya was but the natural choice to be the first chairman.

How I met Malaviya

I was then a stringer for three mainstream English dailies. At the time, there were just a handful of journalists in Dehra Dun; I was the youngest and the most academically qualified. I would meet Malaviya whenever he visited Dehra Dun. He had the special knack of issuing statements that would make news. Like Nehru, Malaviya too had a fondness for Dehra Dun and would often visit the town with his wife Durga. Thus, I was able to develop a good personal rapport with him. With the birth of ONGC in August 1956, the scope of my news coverage from Dehra Dun vastly expanded. I made direct contact with the few senior officers who had arrived to set up infrastructure for the newly born ONGC.

I did not think twice when Indian Express asked me to join as a reporter on its staff in Delhi. Even though the reporting of news in the capital was a different ball game, I soon learned the nitty-gritty and made some useful contacts. My beat was Delhi University, which helped me cultivate a friendship with student leaders. I called on Malaviya on a few occasions. Durga Malaviya had by then started liking me and extended me her innate courtesy and hospitality. ONGC then didn’t have a PRO and Malaviya asked me once if I would like to join ONGC. I happily said ‘yes’ for the simple reason that I would be posted in Dehra Dun. My father was not keeping good health then and needed looking after. But destiny willed otherwise. I was selected via the Union Public Service Commission as an editor in the Directorate of Public Relations & Tourism, Himachal Pradesh, which was then a union territory. I was there for nearly 18 months.

At ONGC

Eventually, I joined ONGC in 1961 and was posted to Baroda. I demurred, but Malaviya told me that Baroda was the happening place where I would find ample opportunity to make use of my journalistic talents. He was right to some extent. We were just about half a dozen officers there trying to set up the nucleus of a regional headquarter that would look after the expanding exploration and allied operations in Gujarat. Ekbal Chand, an IAS officer, was then the chief administrator in charge of the entire Western region. He had known me well enough from Dehra Dun and treated me like family. He called me one morning and asked me to take up additional responsibilities such as labour relations, hospitality of Russian expats and general coordination. I promptly agreed as it would provide me with a good learning experience.

Hands-on chairman

Malaviya knew many of the officers by name as he had handpicked them. He never did flaunt his rank; on the contrary, he showed utmost courtesy and politeness. Malaviya was a hands-on chairman and would ring up the employees if he needed to know anything urgently. Thus, all of us stayed alert for we never knew when Malaviya’s call might come. He would ring me up if he wanted to issue a statement from Delhi about some newsworthy development in Gujarat. It was then my job to dictate the draft press release to his secretary Nayyar, who would take it down in shorthand. On another occasion, there was a rig blowout in Ankleshwar, and Malaviya wanted to release the news from Delhi. I had the temerity to question his suggestion, saying that a release from Delhi would be too late for the Gujarati press and it would then carry irresponsible news. Eventually, a compromise was arrived at and it was decided to release the news simultaneously from Delhi and Baroda. I hastily dictated the content to Nayyar and a time was fixed for simultaneous release of the official version.

Labour pains of a different kind

Both the Ankleshwar and Cambay projects had recruited hundreds of employees on a contingent basis without observing the rules stipulated in various labour enactments. Wherever large employers come, trade unions follow. Baroda-based Sanat Mehta of Hind Mazdoor Sabha was the first to form the ONGC Employees Union. A second ONGC Employees Union under the aegis of the Indian National Trade Union Congress (INTUC) appeared on the scene too under the guidance of Khandubhai Desai, who was then a top INTUC leader based in Ahmedabad. Each of these unions claimed to be the true representative of ONGC employees and sought formal recognition. I had by then done enough homework on labour laws. I asked both the unions in writing to give me proof of membership. Mehta promptly provided the list of members along with the receipts of membership fee. The INTUC union demurred and avoided giving a point-blank answer. I explained in writing the entire situation to the chief administrator and accorded, with his approval, official recognition to Mehta’s union.

That greatly upset the redoubtable Khandubhai Desai who complained against me to Malaviya, accusing me of bias. So gullible was Malaviya that even without seeking a report from Baroda, he issued instructions for my transfer to Sibsagar in Assam. Baroda journalists were aghast at my sudden transfer. Mehta’s trade union, too, condemned my transfer. Even though I felt sad and betrayed, I decided to take it in stride.

A man of integrity

Despite this petty issue, I held Malaviya in great esteem. He was honest and sincere to a fault; no one could ever doubt his integrity. He was truly the founder of the national oil industry. Malaviya died on 27 May 1981. What an uncanny coincidence given that his mentor, Nehru, too had died on the same date in 1964.

On the afternoon of 19 December 1981, then prime minister Indira Gandhi rechristened ONGC’s premier research and development institute in Dehra Dun as Keshava Deva Malaviya Institute of Petroleum Exploration (KDMIPE). A jam-packed auditorium solemnly heard Gandhi deliver a touching eulogy to Malaviya who had died barely six months ago. The PM’s tribute touched a chord in Durga Malaviya’s heart; she was in tears. Devendra and Asha, too, were touched by the fulsome tribute to their father. That was the least the country could do for a man who had devoted the entire second half of his life to creating a network of national oil companies in the country.

The writer is a veteran journalist based in Dehradun and the author of the official history of ONGC, Upstream India

Photo courtesy: M G Sable Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine July 2016

you may also like to read

-

Mental workout

Mukul Sharma tells you how to keep those grey cells ticking Everyone will ultimately lose his or her brain….

-

Helpline

Dr Harshbir Rana answers your queries on personal and social issues related to ageing, elder care and intergenerational relationships ….

-

Off the cuff

Raju Mukherji pays tribute to his first hero, Tenzing Norgay, an exemplary mountaineer Darjeeling, 1955. Dr ‘Pahari’ Guha Mazumdar….

-

Yoga RX

Shameem Akthar shows ways to control debilitating ankle pain through regular practice Ankle pain is so common and prevalent….