Columns

Silvers in the US embrace life with passion and are fiercely protective about their privacy, writes Kamla Mankekar.

It is 16 years since I made the United States my home; but friends still ask me why I moved to this country. “It seems you were quite well-settled in your home in Delhi,” they observe. And I reply, “Because my children were all here; I was alone in Delhi.”

Was that the only reason I left my country to make my home in another? Not really. I surely missed my son and daughters, who over a span of two decades had opted for the US as their home country. I visited them off and on, or they came to Delhi for short vacations. I had come to terms with the fact that none of them would return to ‘live’ with me in India.

After my husband passed away in 1986, I lived by myself for 14 years. To fill the void, I immersed myself in work; I read for pleasure, served on committees and commissions, attended seminars and lectures, participated in discussions, virtually did all that I had little time to do during the last years of my husband’s failing health.

I lived in a neighbourhood developed for media persons, many of whom had been my colleagues and my husband’s co-workers. I had a comfortable house and dependable domestic help. After a period of grieving, I had adjusted to living by myself. Almost imperceptibly, over the years, changes were creeping in and around my life. Things, as one would put it, were not the same.

My friends, who were like extended family and whose company and advice I had sought during my years alone, were disappearing one by one. Residents of Gulmohar Park, where I lived, were journalists who came from different parts of the country: Kerala, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Bengal, and so on. As they retired, they moved back to their ‘native homes’. Senior colleagues and mentors passed away one by one. I felt alone. Delhi Gymkhana Club, where my husband and I had spent many a quiet, relaxing evening, exchanging political gossip with friends from the press fraternity, and listening to suave and knowledgeable members of the civil service, was now swarmed by loud, back-thumping crowds who did not hesitate to corrupt servers with tips (forbidden by club rules) to receive undue service in the bar and dining room. Sunday lunches on the club lawns became a mela where newly enrolled members fought over chairs to seat hordes of their non-member friends, who in turn were duly awed by the grandeur of the club’s colonial building and vast grounds. Decades old and out-of-print precious volumes in the club library were being reported missing as the bewildered Panditji, who had served as librarian for the past 40 years, watched helplessly. I felt an intruder in my old haunt.

Those of Gulmohar Park who moved away from Delhi sold their houses to the highest bidders, mostly non-media persons. Later, to meet the rising cost of living, retired journalists sold their property to builders who constructed multi-storied apartments and made millions selling flats to neo-rich businessmen. The character of Gulmohar Park, which once was an ideal housing destination, changed. The new residents came with retinues of servants: chauffeurs, ayah, cooks and watchmen. Domestic helpers, on whom one had depended for years, deserted old patrons to seek jobs with new employers on fancy salaries. Even storekeepers in the colony hiked prices! One could not compete with the ‘filthy rich’ newcomers.

Delhi too was changing; violence at all levels labelled the city the Crime Capital of the country. It was becoming unsafe for a woman to live alone. My daughter Purnima and son-in-law Akhil, professors at University of California, Los Angeles, suggested I move to Bangalore. They were spending two months there every year and liked its temperate climate and friendly people. They found a house in a beautiful complex. However, it is not easy to strike fresh friendships or locate suitable medical assistance when you are in your 70s, nor to run a household when you do not speak the local language. My option was to move with them to the US.

America, it is believed, is a country for the young; yes, that is so if one is seeking to build a career and get a job. There are few, if any, opportunities for an older immigrant in the job market. Business and professional institutions want young people, preferably with US education and capacity to work from 8 am to 6 pm without absence. It is a different scenario if your children sponsor you and the government gives you the coveted Green Card and ultimately accepts you as a citizen. Seniors in the US are well taken care of by the state with provisions of financial assistance, medical aid and numerous welfare programmes.

Americans are fiercely protective of their personal independence and privacy. I had missed Dorothy, she was nearing 80, in the exercise class at the senior centre; she surfaced after a fortnight looking tired and frail. Dorothy explained she had undergone abdominal surgery and was in hospital for a week and was recuperating now at home. I asked her who was taking care of her daily needs. “Oh,” she replied, “I am managing fine.” Neighbours were helping with grocery shopping, a volunteer came twice a week to clean the place and do her laundry, and she was getting food from Meals on Wheels, a voluntary organisation that provides freshly cooked lunches daily to sick and needy silvers. Dorothy had a son living in the city and he had offered to be with her. But she did not want him to be “meddling around”, she said.

Silvers here retain a healthy zest for life; I was embarrassed when Lucy, a friend from my memoir writing group, offered to introduce me to her retired cousin. “You are so pretty, and young enough for romance,” she remarked. I was then 73. My 82 year-old writer-friend finds it difficult to believe that I never considered having a boyfriend. “Your husband passed away when you were only 58, young enough to remarry,” she said. “And you did not consider having even a boyfriend!” I keep on explaining that for Hindu women, marriage is a lifelong commitment; that in widowhood too we stay faithful to the memory of our deceased spouse.

My American friends marvel at how my son-in-law and daughter have accepted me as part of their life. I am in their social circle, joining their friends at dinners and luncheons, discussing world events and recalling my experiences of the past eight decades of my life. “I can’t ever imagine moving in with any of my children and sharing their life,” my friend Angela has confided in me. She was a venture capitalist and is the mother of two loving daughters and a highly successful businessman son. She is 65 and is looking at retirement housing, another name for homes for silvers.

Life can be lonely and hard when widowed mothers in their sunset years come to live with a son or daughter. As the young couple go to work—a single income is rarely enough to meet the expenses of a growing family—older women are left to mind the house, care for babies and face the bumptious teenage grandchildren. They are the prampushers, popping in painkillers and rubbing arthritic joints with soothing gel.

Life then is no fun.

Mankekar is the author of Breaking News: A Woman in a Man’s World, which chronicles her experiences as one of the first women journalists in India

Photo: iStock Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine March 2016

you may also like to read

-

Mental workout

Mukul Sharma tells you how to keep those grey cells ticking Everyone will ultimately lose his or her brain….

-

Helpline

Dr Harshbir Rana answers your queries on personal and social issues related to ageing, elder care and intergenerational relationships ….

-

Off the cuff

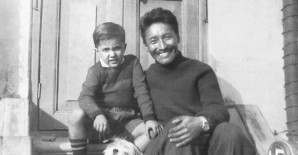

Raju Mukherji pays tribute to his first hero, Tenzing Norgay, an exemplary mountaineer Darjeeling, 1955. Dr ‘Pahari’ Guha Mazumdar….

-

Yoga RX

Shameem Akthar shows ways to control debilitating ankle pain through regular practice Ankle pain is so common and prevalent….