Columns

An avid fan of the cryptic crossword, Bunny Suraiya shares her delightful experiments and experiences with the grid

16 ACROSS. Emperor greets English girl going round Ethiopia’s capital (5,8).

Hmm. I take a strand of my hair in my fingers and twist it round into an almost-ringlet and park it on the top of my upper lip, which curls to hold it there in place. Weird, but that’s what I do when I think. Everyone has their own equivalent of ‘putting on a thinking cap’ and this is mine. I have to figure out the two words that will solve this clue and what makes it harder is that I have solved none of the other clues nearby which could give me a few letters in the blank squares in which this answer is to be filled.

I was a kid of 16 when I met the man who was to introduce me to what was to become one of my lifelong pleasures. My parents and I were at the Saturday Club in Calcutta and my dad said, “This is Brian Uncle.” I looked up at the tall, craggy-faced Englishman, dressed in a tweed jacket, his dark blond hair brushed severely back from his forehead, who looked impossibly ancient to my teenaged eyes, but who couldn’t have been much more than 40 or so. I fell in love with him right away when he held out his hand to me as to an equal and said, contradicting my father firmly, “Not Brian Uncle. Perish the thought. Brian Sinjin Conway—that’s my name and you may address me as Brian.” It was only much later, when I saw his name written down—on a club bill, as it happened, which he insouciantly crumpled and threw away—that I realised that ‘Sinjin’ was the upper-class English pronunciation of St John.

Brian was the epitome of the aristocratic Brit. Unfailingly courteous, extremely well read, and with a delightful sense of humour. He taught me practically everything worth learning: how to bet on the Quinella at the Calcutta races; an appreciation of western classical music (he started my education with Mozart, Bach and Beethoven); a taste for sloe gin (if it was in short supply, which it often was, Benadryl cough syrup made a satisfactory alternative); and how to do the cryptic crossword from the London-based The Times, which used to be published daily in The Statesman in Calcutta. “You have to think logically,” he would advise. “But also tangentially—because the crossword setters have fiendishly convoluted minds. That’s what makes it fun.”

Every day, after my father had finished with the paper, I would pounce on it and—lock of hair firmly planted on upper lip—struggle to make sense of the clues. It would take me all day, in between whatever else I was doing, and in the evening at the club I would show the result of my efforts to Brian. Sometimes I had managed to solve one clue, sometimes a couple more—and Brian would fish out his own nearly always completed crossword and take me through the rest of the clues, one by one, patiently explaining the logic behind each one, and I would say, “Of course! I should have worked that out. How stupid I am!”

And then one day, I hit the jackpot. I actually finished the crossword. All by myself. I couldn’t believe I had really done it. I kept gazing at the completed grid with an idiotic smile on my face, anticipating my meeting with Brian that evening. It went even better than I had expected, because that day happened to be one of the few when Brian was stumped by a clue. It was a DOWN clue and the solution was two words of five and seven letters and when Brian saw it on my completed grid, he said, “Small clothes? What on earth are small clothes?”

“It’s how English gentlemen in Regency times used to refer to their underwear,” I said airily. “It comes from reading Georgette Heyer.”

Brian was impressed. “You’re a brilliant child,” he said, “and we shall have a mug of beer each to celebrate.” And we did.

My passion for the The Times crossword grew stronger after that day and soon I became almost as good as Brian at solving it. On days when there was no newspaper, such as the day after Holi or some other holiday that The Statesman observed, I mooched around, bored and missing my daily fix. And when, at the age of 25, I went to live in London for a while, more exciting to me than the thought of the Big Ben and Oxford Street and all the other delights of what remains my favourite city in the world, was the electrifying thought that I would be able to do The Times crossword on the same day as it was published!

Travelling to my place of work on the Tube every morning from Turnpike Lane to Piccadilly Circus was an exercise in craftiness. For someone at the very bottom of the economic ladder as I was, the idea of buying The Times every day was inconceivable. So I would carefully seek out fellow passengers who were likely readers of The Times (mostly pinstripe-suited city gents with hats and furled umbrellas) and position myself such that I would be able to make a grab for their discarded newspapers if they left them behind on the train before my stop.

This ploy worked four days out of five, and on the odd day when I was unlucky, as well as during the weekends, I learned to live without the crossword, but it was a pleasure lost, and I doubt if there was ever a more delighted office-goer than me when the week began again. No Monday morning blues for me—not when the stimulation and excitement of getting my hands on the crossword was a possibility!

14 DOWN. Highly curious after crime? Sounds like it in place of worship (9)

As hard as it is to solve a crossword, it’s infinitely harder to set one, because the setter has to work backwards! When we returned to India, my husband was working on The Statesman Literary Supplement and the idea was mooted that it might be interesting for its readers to have a literary crossword to solve once a week.

But buying crosswords from foreign papers was expensive—it still is, which is why no daily paper in India has a cryptic crossword worth doing—and so my husband offered to compile a weekly crossword and he asked me to help. I was thrilled. And that’s when I realised what an enormous labour of love it is for those who compile crosswords every day of the week. I hope they get paid very well, because it’s certainly not an easy thing to do.

The first and the most important thing to consider is the grid. This has to be—like a chessboard—perfectly square. And, something a lot of people don’t realise, it has also to be perfectly symmetrical. This means that the left and right halves of the grid, as well as the top and bottom halves, have to be mirror images of each other. All too often in magazines one sees crosswords where the grid is asymmetrical, with a collection of black and white squares randomly placed and of unequal lengths—those are not at all correct and show that the compiler has no basic understanding of how crosswords are formed. For amateur compilers like my husband and I, the easiest way to get a perfect grid was simply to photocopy one each week from the main paper that still carried the cryptic crossword from The Times.

Next came a task that was even more demanding, if such a thing could be possible: filling in the light squares with words. The first time we sat down to it, we thought it would be a breeze, and started filling in the squares with a ballpoint pen, convinced it would be the work of 10 or 15 minutes at the most. After we had ruined the grid by overwriting the words dozens of times to make them fit and interlock with each other, we realised we had quite a job on our hands. We made a fresh photocopy of the grid, and this time with pencil in hand and an eraser nearby, we started again—filling in the words lightly and tentatively, only to have to continuously erase them and start over. It took hours because the symmetry of the grid is sacrosanct and has to be maintained no matter what. So the words have to be chopped and changed because the grid cannot be.

Once all the words are finally in place, that’s when the fun part begins: compiling the clues to the words. Here’s where you can let your fancy roam, and make the clues as cryptic and devilish as you like, provided you observe one cardinal rule: the clue has to be devised in such a manner that the final answer fits it exactly, with no ambiguity whatsoever. The solution has to have the elegance of a geometry theorem. There can be no two answers, and once the solver has the answer, it must be demonstrably correct. QED.

This is proof that crosswords—for setters and solvers alike—are among the most exciting and stimulating brain games ever. The more you travel, the more widely you read, the more experiences you allow yourself to be open to, the larger your vocabulary, the better at crosswords you will be and the more fun you will have. And now that it’s possible to freely download the day’s cryptic crossword from The Guardian and The Observer in London (as well as the one from The Times at a small fee), it costs nothing—or next to nothing—to get your daily dose of mental callisthenics. What could be a better reason for waking up every morning?

P.S. If you haven’t yet solved the clues above, here are the answers:

16 ACROSS: Haile Selassie (That’s the Emperor; hails is another word for ‘greets’ and it incorporates ‘e’ which is the capital of Ethiopia; followed by English girl, i.e. E lassie).

14 DOWN: Synagogue (a place of worship that ‘sounds like’ highly curious, i.e. agog, after crime, i.e. sin).

Bunny Suraiya is a writer, reviewer and crossword addict. Her acclaimed novel, Calcutta Exile, is soon to be published in France

Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine November 2013

you may also like to read

-

Mental workout

Mukul Sharma tells you how to keep those grey cells ticking Everyone will ultimately lose his or her brain….

-

Helpline

Dr Harshbir Rana answers your queries on personal and social issues related to ageing, elder care and intergenerational relationships ….

-

Off the cuff

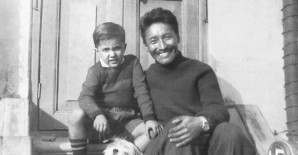

Raju Mukherji pays tribute to his first hero, Tenzing Norgay, an exemplary mountaineer Darjeeling, 1955. Dr ‘Pahari’ Guha Mazumdar….

-

Yoga RX

Shameem Akthar shows ways to control debilitating ankle pain through regular practice Ankle pain is so common and prevalent….