Columns

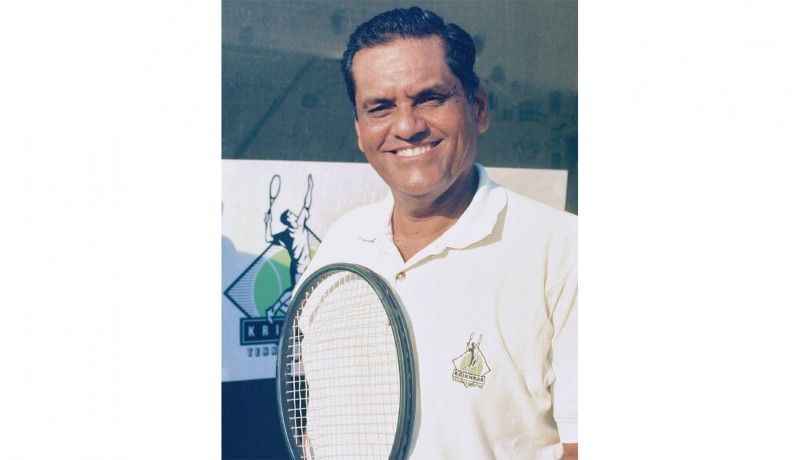

With remarkable dexterity and exceptional consistency, Ramanathan Krishnan was India’s best-ever tennis player, writes Raju Mukherji

In the 1960s, the distinction between the amateurs and professionals in tennis was thoroughly followed. The professional players would go around the world playing in their own circuit, which was unofficially known as the ‘Jack Kramer Circus’. Top professional tennis players of the period were Pancho Gonsalves, Lew Hoad and Ken Rosewall. On the other hand, the doors to Wimbledon and Davis Cup as well as other prominent tennis championships were the exclusive prerogative of the amateurs.

The top amateurs of the time were not inferior to the professionals in playing ability. In fact, the best of amateurs, when they converted themselves to ‘professional’ status, were invariably among the best of pros as well. Men like Rod Laver, Roy Emerson, Manuel Santana, Alex Olmedo and Neale Fraser dominated the amateur tennis scenario in the 1960s. In such a heady atmosphere, India, too, had a representative, Ramanathan Krishnan, a tennis player of exceptional artistry from Chennai (then Madras). He was deservingly ranked World No. 4 at the time by virtue of recording regular victories against the best of oppositions in international championships on various playing surfaces all over the world. No other Indian has ever been ranked as high as maestro ‘Krish’.

Krishnan’s strength lay in his court craft and temperament. With a tennis racquet in hand, he gave the impression of being a sorcerer with a magic wand. He never seemed to hurt the ball, merely caress it.

At a time when players were concentrating hard on a booming service and power play, Krishnan was an outstanding exception relying on subtle touches and deft placement. His approach was not of an aggressive ‘killer’ but a silent saint out to prove everybody wrong by his sacred touch. Even his physique defied accepted norms. He was not lean and athletic. Nor did he possess the tough appearance of a champion sportsman. No bulging muscles protruded, nor did the jaws square up to size up an opponent. No furrowed eyebrows were displayed: he was perennially relaxed and smiling.

Rather Ramanathan Krishnan’s big, burly figure created an impression of a contented man in retirement. Content he certainly was with his craft and confidence, with his skill and strategy. But he was in no kind of retirement. On the contrary, he would be active enough to send others into a dizzy form of reverie.

Amazing shots from improbable angles and miraculous turnarounds from almost lost causes were his forte. From 2 sets down, the way he defeated Thomas Koch of Brazil in a Davis Cup encounter at Calcutta’s South Club lawns in 1966 is still spoken of with awe by all those who were fortunate to get a seat in the packed stands at Woodburn Park that winter afternoon.

India and Brazil had won two matches each. Now in the crucial fifth match for India, Krishnan, after trailing 1-2 sets, was down 2-5 on points and 15-30 in the 8th game. How he manoeuvred that certain defeat into an improbable victory is beyond words. At the end of the match, no one moved. Still silence prevailed till his opponent Thomas Koch began to applaud. As a 16 year-old in the stands, I realised I had just seen a miracle. As we left the venue drenched in emotion and sweat, Krishnan happened to be the only one in the arena who displayed no trace of emotion; no sign of sweat!

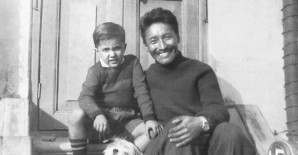

Born in Madras on 11 April 1937, he learnt the fundamentals and nuances of the game from his tennis-player father ‘TK’, who was the runner-up to Ghaus Mohammad in the national tennis championship in 1939. Early in life, young Ramanathan exhibited remarkable dexterity and combined it with exceptional consistency. Soon his name and fame spread all over the tennis globe.

While a student at Loyola College in 1954, at the age of 17, he won the Junior Wimbledon title by beating talented American Ashley Cooper. In 1958, Ashley Cooper went on to win the Senior Wimbledon crown. Surprisingly, despite his prolific victories around the world, this was one crown at the centre court of Wimbledon that Krishnan could never conquer.

Krishnan had the habit of defeating the very best of international players in almost all major championships. But the All-England title at Wimbledon eluded him forever. Twice, he reached the semi-final at Wimbledon, only to lose to the ultimate winner on both occasions. Ironically, he had defeated both the winners, Fraser and Laver, at Queen’s Club just days prior to the respective Wimbledon championships.

No Indian player, before or since, has been ranked higher than he was in the international rankings. Unfortunately, in his time, tennis had not become an Olympic sport; if it had been, Krishnan would have walked away with Olympic medals galore. Initially with Naresh Kumar and later with the highly talented Jaidip Mukherjea, both from Calcutta, he formed a deadly doubles combination that did wonders for India, particularly in Davis Cup encounters. At the time, in the 1960s, India was a major tennis power in the Asian context.

Krishnan and Mukherjea were magnificent in their doubles victory in 1966 over the highly fancied World No. 1 pair of John Newcombe and Tony Roche in their own den in Australia in the challenge round (the final) of the Davis Cup. This win against all odds has gone into the annals of tennis history. That day, the Melbourne tennis fraternity gave the duo a standing ovation. The Australian media went haywire describing the artistry and sportsmanship of Krishnan and Mukherjea. This was indeed a rare, unusual gesture from the highly partisan Australian media and crowd.

Krishnan, Naresh Kumar, Jaidip Mukherjea and Premjit Lall were model-sportsmen in court craft and conduct on and off the field. They were impeccable sports ambassadors of the country. “With Krishnan around, one felt proud to be an Indian,” wrote Subroto Sirkar, India’s leading tennis correspondent at the time. “We were always treated very well around the tennis world.” Even the media got the benefit of Krishnan’s presence!

Apart from the man’s superb court skills, it was his bearing that left a permanent imprint in the minds of tennis followers, world over. Cool and composed, his laidback approach was distinctively different from the rest. The execution of his shots had a remarkable ring of beauty attached to it. The beauty of simplicity.

And such was Krishnan’s sense of sportsmanship that he would never dispute a line call. In fact, at Calcutta South Club during the Brazil-India tie in 1966, a disputed line call went in Krishnan’s favour. In the next point, believe it or not, he purposely put the ball out of court to give a point to his opponent! Writing on Krishnan, senior sports journalist K R Wadhwaney wrote, “Off the court he spoke softly. Even after winning a match, he would gently say something to the opponent giving the impression that he was sorry for winning the match!”

Krishnan, the gentle giant, would never force his opinion on others. He would speak softly and slowly. Would not advise unless asked for. Respectful to seniors, he was very courteous to juniors as well. He had no sense of ego; no sense of vanity. Such was his popularity that people would come to meet him in Chennai from all over the world just to say ‘hello’. Tennis legend Harry Hopman’s wife flew in from the US—almost 30 years after Krish’s retirement—to wish him on his 60th birthday in 1997.

The Arjuna Award in 1961 was followed by the Padma Shri in 1962 and the Padma Bhushan in 1967. International awards, too, came in profusion. But nothing could alter the man’s exceptional equanimity. Whatever he did, he did with an innate sense of ease. Nothing and nobody could disrupt his unique style, intelligent approach, strategic planning, remarkable artistry, and constantly evolving tactics. He never needed publicity agents, influential parents, support systems or physical trainers.

Indeed, Ramanathan Krishnan proved to the world of sports that even the softest of gentlemen can overcome the gamesmanship of sly opponents; that a vegetarian diet was no impediment to sporting success; that one does not need media support to become a champion. He was a rare sportsman, a rare human being. Shall we see his like again?

Kolkata-based Mukherji is a former cricket player, coach, selector, talent scout, match referee and writer

Photo courtesy: Krishnan Tennis Centre Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine April 2018

you may also like to read

-

Mental workout

Mukul Sharma tells you how to keep those grey cells ticking Everyone will ultimately lose his or her brain….

-

Helpline

Dr Harshbir Rana answers your queries on personal and social issues related to ageing, elder care and intergenerational relationships ….

-

Off the cuff

Raju Mukherji pays tribute to his first hero, Tenzing Norgay, an exemplary mountaineer Darjeeling, 1955. Dr ‘Pahari’ Guha Mazumdar….

-

Yoga RX

Shameem Akthar shows ways to control debilitating ankle pain through regular practice Ankle pain is so common and prevalent….