Etcetera

While a regulatory framework is vital for senior-care facilities, the need of the hour is to develop an ecosystem to take care of silvers, reports Sai Prabha Kamath

Last month, we reported the release of the ‘Model Guidelines for Development and Regulation of Retirement Homes’ by the Union Housing and Urban Affairs Ministry, prescribing norms for an elder-friendly environment in retirement communities (A Welcome Initiative). The guidelines came at an appropriate time—in fact, in February, the Madras High Court had directed the Tamil Nadu government to inspect old-age homes in the state and file a report, further to a PIL alleging that residents of certain retirement homes in Coimbatore had been taken for a ride in terms of provision of basic minimum facilities.

While developed nations have a comprehensive regulatory framework to set up and run senior-care facilities, there have been no model Acts or guidelines in India. “This has led to a rapid increase in a variety of players with varying definitions of quality of senior care,” says CII – Senior Care Industry Report 2018. “It is important to evolve a regulatory framework that promotes quality and service excellence in senior-care facilities and prevents misuse of such facilities amd programmes and ensures high quality care to the end benefactor.”

RETIREMENT HOMES VIS-A-VIS OLD AGE HOMES

While the ‘Model Guidelines for Development and Regulation of Retirement Homes’ prescribes norms for private retirement communities, what about regulating other old-age homes and senior facilities?

“All old-age homes should be under some universal guidelines; there should be a framework to guide and monitor them,” says Sailesh Mishra, founder-president, Silver Innings, a social enterprise that runs an assisted living elder care home, A1 Snehanjali, in Maharashtra.

“Senior living is distributed into eight formats: independent living, assisted living, skilled nursing facility, continuing care retirement community, memory care facility, senior day care, persons with disabilities care and palliative care,” explains M H Dalal, founder and chairman of Association of Senior Living India (ASLI) and CMD of Oasis Senior Living. “A senior-care facility can have one or more of these specialised formats within the same facility. As a country with over 130 million silvers, it is vital that regulatory efforts in this direction keep in mind different formats of care as is the case in globally evolved markets.”

Meanwhile, Colonel Achal Sridharan, managing director, Covai Property Centre, says, “As for rural areas, the requirement is large. Seventy per cent of our elders are in rural segments and their problems are worse as many of their children have moved out of the villages. The Government—the Centre and states—cannot provide for the rural elderly. However, corporates can do it through CSR. We not only need funds but commitment to care for them.” (Read full interview below.)

In fact, Tata Trusts, which has initiated various programmes in the elderly care space since 2016, had released its Report on Old Age Facilities in India last year with a vision to demonstrate models of good practices to address the needs of the elderly. “The study was commissioned to understand the global practices of running old-age homes and senior-living facilities and how these can be applied to senior homes in the country,” says Sugandi Baliga, head – Elderly Care, Wellness and Engagement Programme, Tata Trusts. “This study has also used the guidelines of the Tamil Nadu government.” To conduct the study, Tata Trusts joined hands with Samarth, a support group that enables independent life among elders, and UNFPA (The United Nations Population Fund). “There is a huge need to develop models of good practices for healthy living and continuous engagement so that people can live within their own homes with programmes that will keep themselves active.”

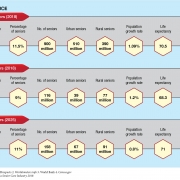

THE BURDEN OF AGEING

The study had highlighted the challenges the country will face with the growing numbers of people above 60. Indeed, India has been classified as an ‘ageing country’ by the UN, with 8.6 per cent of the total population being 60+. This number is expected to triple by 2050, constituting 20 per cent of the population. The study was conducted on a survey based on a sample set of 480+ old-age homes and 60+ senior-living developments in India cutting across geographies, size, cost, facilities, ownership and management. Based on the 2011 census of India, the survey arrived at an estimated 1,150 facilities and the capacity to house around 97,000 elderly residents.

More significant, the findings of the study were appalling, to say the least, with a yawning gap between expectations and delivery at most elder-care facilities. Senior facilities run by private organisations and charity homes only address the needs of a fraction in the country and there was no way to measure the quality of services. This renders elderly residents vulnerable with no impetus for the facility owners and managers to improve. Forecasting likely demand driven by the increasing elderly population and change in preferences owing to availability of new products and socioeconomic norms, the study highlighted the crying need to enhance capacity almost eightfold to tenfold over the next decade.

“We are, of course, not prepared,” laments Dalal. “We are far behind the curve by at least a decade. We don’t have any traction even at the moment. The current pipeline of senior-care units does not even cross five figures.”

DEVELOPING MINIMUM STANDARDS

Data collected from site visits, expert interviews and study of benchmarks were used by Tata Trusts in the selection of design principles to develop frameworks for implementation of standards at senior homes. It came up with five key areas that offer a set of comprehensive, measurable and practical standards for senior facilities. The areas are: 1. Infrastructure 2. Physical needs 3. Safety and security 4. Dignity and respect 5. Administration and management. The minimum standards were developed with sensitivity to the Indian context of affordability, variety, ownership, regulatory sophistication and experience with implementation.

The study recommended that these minimum standards be implemented through compulsory registration, annual filings and periodic inspections, apart from a voluntary accreditation process. “This report was shared with experts and practitioners, the CII, and ASLI group members and the revised minimum standards were finalised,” says Baliga. “The final document has been submitted to the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment (MoSJE) to be used in the amendment that is suggested in Maintenance Act (2007).”

THE CONSTRAINTS

With multiple studies and researches having been done in this segment, very little has been achieved in terms of maintaining standards at senior facilities across the board. “Recommendations and orders for implementation are different,” says Col Sridharan. “Unless the legislative authority as well as judiciary understands this segment entirely, as in western countries, we will end up removing our compassion and commitment.” Mishra agrees, saying, “Until the regulations are passed in Parliament and made law, it won’t work.”

IMPLEMENTATION OF GUIDELINES

While forming guidelines for minimum standards is important, this just addresses one part of a larger issue. Who will drive implementation?

“Surely, implementation will always be by the operator with checks and balances duly audited. It will be different for the rural model, if it is not run by an operator. We need to have an excellent redressal mechanism aided by technology,” suggests Col Sridharan. “Do have an elected resident committee to take to task black sheep who are not providing services and care up to the minimum standards. But also understand what some retirement community services and care providers are doing and how they are upgrading their services and care with the help of technology.”

Calling for a third-party rating system, Mishra recommends, “The Central Government should first come up with minimum guidelines for old-age homes run and managed by the Government, NGOs and the private sector. Every state and Union Territory should make implementation mandatory under the supervision of MoSJE or the Housing Ministry.”

NEED OF THE HOUR

At a time when elder care in India is largely neglected, the solution lies in not just building homes and facilities. “The question is larger: just how many homes can we make?” remarks Mishra. “All over the world, only a fraction of people stay in facilities such as old-age homes and nursing homes. The majority stay in their house. The whole idea is to encourage community living and ageing in place, where good services, assisted living and day care are available at your doorstep. For the marginalised, the Government should provide free homes and night shelters.”

Indeed, the need of the hour is to develop an ecosystem to take care of silvers, both in urban and rural areas. For instance, Tata Trusts has initiated some pilots in the urban and rural sectors along with state governments to develop a model that is sustainable and can address the needs of the elderly. “The concept of activity centres at urban hubs is being initiated to promote programmes for active engagement of senior citizens for healthy living. In the rural sector, the focus is on addressing the basic healthcare needs of the elderly and setting up village activity centres through state government and local administration support,” says Baliga. “Additionally, in Hyderabad, we are in the process of setting up a toll-free number to enable solutions for the elderly through a single platform.” This will provide free information, counselling and field services that will focus on the needs of the elderly.

“The main problem is that we, as citizens, view elders as a problem. Treat elders with dignity and respect,” urges Col Sridharan. He recommends the creation of a separate ministry apart from the appointment of a minister, both at the Centre and state level, holding independent charge. “Undertake a study or call all stakeholders who have studied this segment to find solutions. Where the Centre and state governments are involved, commitment in terms of finance must be accepted for the elders living in rural areas or those who are marginalised and have nowhere to go. Lay down minimum standards.”

Proposing a multi-dimensional approach towards ageing, Mishra says, “Strengthen and empower families, encourage start-ups, promote social enterprises, allow second careers, start universal social security at a young age.”

We couldn’t agree more!

“What we are doing is Citizen Social Responsibility”

Colonel Achal Sridharan, managing director, Covai Property Centre, charts the way forward for senior-care facilities in India

According to the Report on Old Age Facilities in India by Tata Trusts, senior citizens’ homes run by private organisations and charity homes only address the needs of a fraction. In fact, the need for senior living may rise to around 8-10 lakh beds in the next 10 years, an eightfold to tenfold increase over the current base. Are we ready for this challenge? How can we prepare ourselves?

The report is indeed right. We need to discuss two segments: old-age homes run by the Government, charitable institutions and NGOs; and senior care facilities run by private players.

At a time when 98 per cent of our seniors live outside retirement communities, home care has become a necessity. Unfortunately, we do not get trained caregivers for home care and the available untrained caregivers do not stick to one job.

We need to look at senior living and care separately for urban and rural areas. While private players are necessary, the rules and regulations thrown at them should not deter more players from entering this segment, where today most service and care providers have a real-estate background. While urban areas can have retirement communities, we need CSR funding in the rural segment. Except for a few big corporates, such as Tata Trusts, not many funds are available from CSR. The Centre and state governments may not have the means to pump in resources and manage these old-age homes. And CSR for this segment is a pittance.

In this scenario, we, at CovaiCare, care not only for the seniors but, after their demise, their children with special needs. Such requirements are not even considered but the need cannot be wished away.

The findings of the study also reveal a yawning gap between expectations and delivery of services at most elder-care facilities in Tier 1 & 2 cities. What needs to be done to improve their conditions?

Seniors go to a particular retirement community after vetting and checking the antecedents. They know what they will get and how much it will cost. Yes, there are a few black sheep but the majority are committed to the cause of seniors. Many of us have moved with the times to not only improve services but check our own quality of services with the help of technology.

Further to the ‘Model Guidelines for Development and Regulation of Retirement Homes’ released last month, do you think it is time for the residents of old-age homes in urban and rural areas to get their dues?

I wish ASLI, HelpAge India and some of the trusts involved in elder care had been consulted before issuing the guidelines. I am not of the view that elders in retirement communities are not getting their dues. That question would be from a preconceived mindset that all of us are out to make money and make the elders suffer. Please ask our residents. Do a survey. Barring a minuscule few, who have been named in the PIL in Madras High Court, we as a company or individuals toil for the seniors in our community.

In 15 years of Team CovaiCare looking after elders, not one has died while being evacuated to a hospital in an emergency situation. From mere ‘living’, we have graduated to ‘care’ in its various manifestations. Please visit Ashiana, Mantri Primus, Brigade Group, Tata Housing and many more in this segment. Some are doing yeoman’s service in looking after dementia and Alzheimer’s patients. There are many unsung heroes too. Many of us do much more that what is stated in the guidelines issued last month.

CovaiCare is the only one in the world that cares for persons with special needs after the demise of their parents until their death; we run workshops for elders to prevent falls; we have a PolyCare Centre connected to all our retirement communities through the Internet and provide telemedicine facilities so that our elders need not go to hospitals, spend time and waste money. These services cost a pittance and are mostly funded by us.

As for rural areas, the requirement is large. Seventy per cent of our elders are in rural segments and their problems are worse as many of their children have moved out of the villages. The Government—the Centre and states—cannot provide for the rural elderly. However, corporates can do this through CSR. We not only need funds but commitment to care for them.

Despite provisions in the National Policy, nothing substantial has been implemented to address the needs in elder care. Please comment.

I agree. A lot more needs to be done if the Government is indeed serious about elder living and care. I suggest we have a separate ministry and minister instead of dealing with senior citizens under Social Welfare and Justice.

The problem is that the National Policy on Elders is to be implemented at the state level whereas the policy has been issued by the Centre. In a federal structure of governance, this will always be a problem. No one has given this segment of senior care the importance it deserves. Guidelines, rules and regulations will only be on paper. While all of us feel society’s attitude has changed, elders are not getting their dues in terms of services and care. Our tradition of looking after our elders is thrown to the winds; they are being abused and neglected. Who is to take the blame? All of us, of course. In such a scenario, if some of us are willing to go that extra mile to provide services and care, it is not because of money but passion and commitment. What we are doing is Citizen (not Corporate) Social Responsibility. And we get nothing in return and our senior citizens in our retirement communities are asked to pay 18 per cent GST for services and 5 per cent for eating food. Is this fair?

What needs to be done to increase the number of affordable senior homes?

Thanks to longevity, the senior communities planned and executed today are in the affordable housing model of the Government of India. This is because seniors need to save money for care requirements with advancing age. Corporates can chip in by helping those in rural segments with housing, services and care. We need data to work out the requirement of affordable retirement communities in the private sector as well as rural areas.

Country insights

SINGAPORE: With a senior population of 1.8 million, Singapore needs 17,000 senior care units by 2020. To prepare for the ageing population, the government is working towards a successful ‘ageing-in-place’ lifestyle and accessibility as a key enabler. The government has actively incorporated barrier-free access and ‘Silver Zones’ to enhance road safety for the elderly. Various models are under evaluation to allow elders to stay in their homes, or to share residences between three to four seniors who can live together.

CHINA: With over 1.4 billion people, the senior population in China is among the fastest-growing demographics. Although China’s great potential in the senior housing market has attracted investor interest, the entire market is at a preliminary stage, facing challenges such as insufficient effective demand, a mismatch between supply and demand, unclear micro policies and financing channel restraints. About 6-7 per cent of the senior population lives in community-based senior living and 3-4 per cent lives in institutional housing. China will need 4.0-5.2 million senior units by 2020.

AUSTRALIA: With a senior population of about 36 million, Australia has one of the best aged-care systems in the world. The most popular form of senior living in Australia is retirement villages; there are approximately 2,000 retirement villages supporting 190,000 residents across Australia. Villages offer an independent lifestyle with one-to-three bedroom units.

THAILAND: As Thailand becomes an ageing society with 7.5 million seniors above 65, more senior housing projects by both government bodies and private developers are emerging across the country. While most of these projects are aimed at accommodating the ageing Thai population, luxury senior housing developments in the country’s resort destinations are springing up to cater to foreigners and affluent Thais. The demand for senior-living units in Thailand is about 800,000 units.

Source: CII – Senior Care Industry Report 2018

Demand-supply gap in senior living in India

The current senior housing demand from the urban and rural sectors is about 2.4 lakh houses and 51,500 houses respectively, of which the higher-income group (HIG) is 60,000 and middle-income group (MIG) is 70,000. The current senior housing supply across 37 senior living players across all formats and economic segments is 20,000 units. Fifty-three per cent of total senior living units are operational, comprising 10,722 functional units, followed by 20 per cent under-construction units.

Source: CII – Senior Care Industry Report 2018

Old-age homes in India

- Total no. of homes: 1,279

- Homes that provide services free of cost: 543

- Pay-and-stay homes: 237

- Homes with both free and pay-and-stay facilities: 161

- Homes that provide medical/constant care: 214

- Homes exclusively for older women: 133

Source: Help Age India

Photo: iStock April 2019

you may also like to read

-

Cracking the longevity code

Small yet impactful choices can be game-changers, writes Srirekha Pillai At 102, there’s no stopping Chandigarh-based Man Kaur, the world’s….

-

Birthday Girl

Published in a special edition to honour Japanese master storyteller Haruki Murakami’s 70th birthday, Birthday Girl (Penguin; Rs 100; 42….

-

A huge treat for music lovers

Published as the revised and updated second edition, Incomparable Sachin Dev Burman (Blue Pencil; Rs. 599; 470 pages) the authoritative….

-

Second wind!

Written all of 50 years ago, Whispering Waves (Yatra Books; Rs 599; 300 pages) by Sita Nanda is a nostalgic….