Etcetera

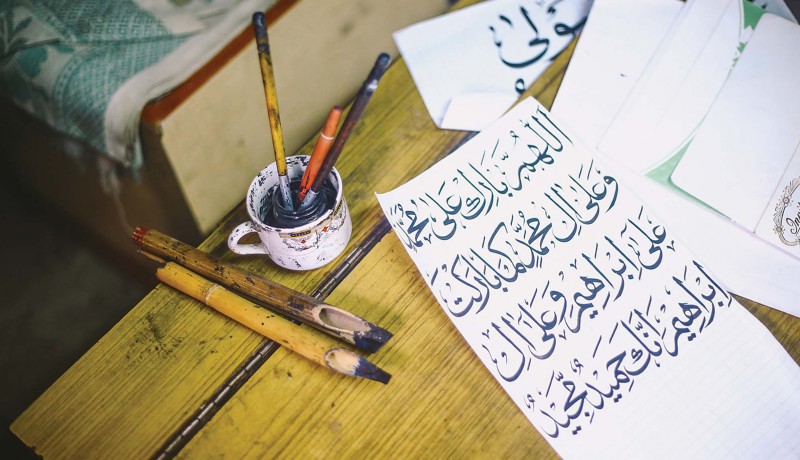

Delhi’s katib write the last chapter in the city’s Urdu Bazaar

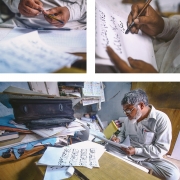

Katib Mohammed Ghalib, 54, has very little to do these days. There was a time when he would stay seated for hours, head bent almost reverentially over sheets of paper, and leave a trail of beautiful handwriting in his wake.

As the hours wore on, Ghalib brought poetry to life, imprinted news on handwritten newspapers and magazines, and etched stories in books whose covers were decorated in gold foil. He is one of only three surviving katib or Urdu scribes in Old Delhi’s Urdu Bazaar, a market near the southern gate of the Jama Masjid.

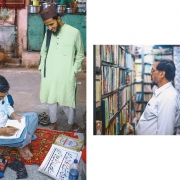

Till a couple of decades ago, the market was a hub for Urdu poets, writers, scholars, intellectuals and publishers, and it teemed with scribes like Ghalib, whose Urdu, Arabic and Persian calligraphy has graced the pages of religious texts, travelogues, essays, speeches, biographies and fiction. Today, Urdu Bazaar has more eat-outs and noisy clothing stalls than bookshops, and its three scribes have been reduced to writing the titles of books, wedding invitations, and wedding and birth certificates.

“A few months ago, a man from Chandigarh came looking for us. He phoned me but I was not feeling well that day, so he returned without getting his work done,” says Ghalib, who works out of the Kutub Khana Anjuman-e-Taraqqi-e-Urdu bookstore, one of the biggest bookshops in the market.

Ghalib, a native of Ambala, was the first person in his family to receive an education. He, like several other katib, learnt the craft at Darul Uloom Deoband, an Islamic school in Saharanpur, Uttar Pradesh, close to Ambala. “I elected to learn calligraphy because this was a respected profession, one from the time of the Mughal kings,” says Ghalib, twirling a flat-nibbed, hollow wooden pen that doesn’t see much work these days.

“In the old days, it took 50 to 60 scribes working eight to 10 hours per day to complete a newspaper. When I was young, it would take me up to three months to complete a 200-page book, while also working on other assignments,” reminisces Ghalib.

A few lanes down, we find Katib Abdur Rahman, 62, who learnt his craft at the Ghalib Academy in Nizamuddin, New Delhi. “I have six children but I don’t see the point in them taking up this work, when the art is trying hard to survive,” he says.

Not only is there little demand for handwritten literature these days, few are willing to commit the patience and dedication it takes to become a calligrapher, says Rahman. “I invested two years learning to write Urdu and two years to write Arabic. These days, there are no returns on that investment.”

Our third scribe, Mohammed Tehsin, a septuagenarian, is nowhere to be found. Neighbouring shopkeepers say he hasn’t been coming around much, instead spending most of his time with his children and grandchildren. Tehsin knows that his beloved Urdu Bazaar is writing the last chapter in its history.

Photos: Sumukh Bharadwaj Text: Natasha Rego Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine April 2017

you may also like to read

-

Cracking the longevity code

Small yet impactful choices can be game-changers, writes Srirekha Pillai At 102, there’s no stopping Chandigarh-based Man Kaur, the world’s….

-

Home, not alone

While a regulatory framework is vital for senior-care facilities, the need of the hour is to develop an ecosystem to….

-

Birthday Girl

Published in a special edition to honour Japanese master storyteller Haruki Murakami’s 70th birthday, Birthday Girl (Penguin; Rs 100; 42….

-

A huge treat for music lovers

Published as the revised and updated second edition, Incomparable Sachin Dev Burman (Blue Pencil; Rs. 599; 470 pages) the authoritative….