Etcetera

We’ve all been weaned on Indian mythology—captivating tales with larger-than-life characters told in binaries, virtue and valour pitted against villainy and venality. The women in these narratives are, more often than not, relegated to the side lines or rendered one-dimensional.

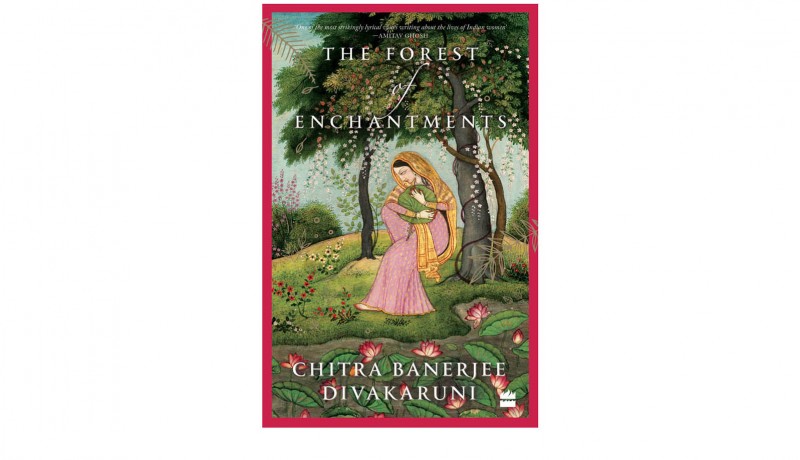

That’s what makes writers like Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni so important. Her insistence on bringing women to the centre of her canvas, making them real and relatable, and amplifying their voice, is more relevant than ever today. And her ability to do this with such facility and grace of prose makes not just her characters but her writing accessible to readers across generations and geographies. The success of her rendering of Draupadi in The Palace of Illusions is testament to this.

Now, with her latest offering, The Forest of Enchantments (HarperCollins; 372 pages), it’s Sita’s turn.

How else could I write my story except in the colour of menstruation and childbirth, the colour of the marriage mark that changes women’s lives, the colour of the flowers of the Ashoka tree under which I had spent my years of captivity in the palace of the demon king?

Thus begins the Sitayan as she sits in Sage Valmiki’s ashram and dips her quill into red ink, telling her story that remains ageless and timeless. The difference is that Divakaruni’s Sita is everywoman—she is abundantly human, brimming with hopes and talent, not the passive, meek goddess popularised in lore but a livewire, as quick to irritation as she is to joy, a prisoner to duty but freed by the courage of conviction. And there is so much of the quotidian in her interplay with Ram (who is as complex and imbued with the same mortal failings) that it sometimes makes you forget their ‘divinity’.

But this book is not just about them. The women usually consigned to the fringes of this epic are brought to its heart: Kaikeyi, Kaushalya, Surpanakha, Mandodari, Ahilya and, notably, Urmila, “the forgotten one”, all find a voice. For, without them, as Sita acknowledges, her story “can’t be complete”. The telling of their realities, in conjunction with hers, reinforces certain truths: while female strength can take innumerable forms and the resilience of women is inestimable, their talent and worth are often ignored, their potential overlooked. And as they age, they are even more marginalised. As Divakaruni tells us in an exclusive interview, “Women face the same challenges as Sita even today.”

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of this book, though, is that it is equally a treatise on the nature of love as both an enabler and obstacle to happiness.

Sita’s first lesson on the nature of love—that in a moment it could fulfil the cravings of a lifetime, like a light that someone might shine into a cavern that has been dark for a million years—is followed by deeper learnings on its contradictions: Even the strongest intellect may be weakened by love. This struck me as paradoxical. Shouldn’t love make us more courageous? And even more significant: Such is the seduction of love: it makes you not want to think too much. It makes you unwilling to question the one you love. And finally: Because this is the most important aspect of love, whose other face is compassion: It isn’t doled out, drop by drop. It doesn’t measure who is worthy and who isn’t. It is like the ocean. Unfathomable. Astonishing. Measureless.

Interestingly, while her love for Ram often shackles her, it is her love for her children that, ultimately, sets her free. A single mother in every sense of the word, she vows to teach them everything they need to know to be princes. But more than that, I’ll teach you what you need to know to be good human beings, so that you’ll never do to a woman what your father has done to me. And that duty done, when Ram demands she prove her innocence one last time, she brooks no further injustice: Because this is one of those times when a woman must stand up and say, ‘No more!’

Indeed, Divakaruni’s Sita is, as she describes in her beautiful foreword, a goddess, daughter, sister, lover, warrior, mother—and role model. “Sita’s story has much in it to inspire and console us all,” she writes. “And…I hope that it brings new meaning to that old blessing: May you be like Sita.”

I think we already are—and it is a thought both empowering and sobering.

—Arati Rajan Menon

Read our exclusive interview with Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni

March 2019

you may also like to read

-

Cracking the longevity code

Small yet impactful choices can be game-changers, writes Srirekha Pillai At 102, there’s no stopping Chandigarh-based Man Kaur, the world’s….

-

Home, not alone

While a regulatory framework is vital for senior-care facilities, the need of the hour is to develop an ecosystem to….

-

Birthday Girl

Published in a special edition to honour Japanese master storyteller Haruki Murakami’s 70th birthday, Birthday Girl (Penguin; Rs 100; 42….

-

A huge treat for music lovers

Published as the revised and updated second edition, Incomparable Sachin Dev Burman (Blue Pencil; Rs. 599; 470 pages) the authoritative….