Etcetera

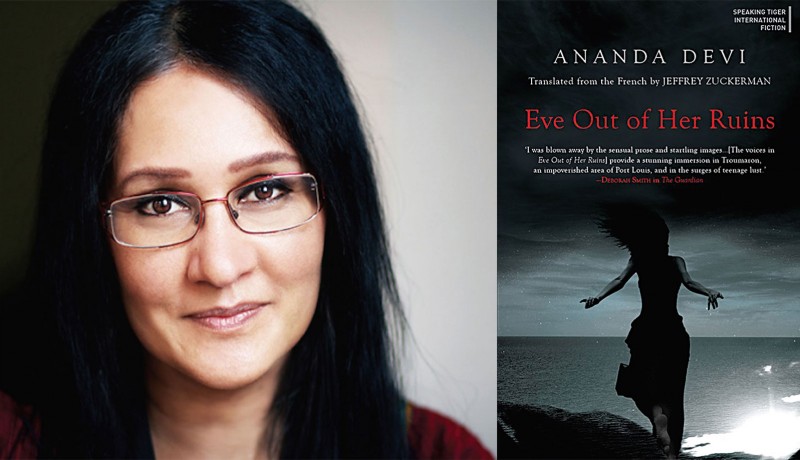

Narrating the bad and ugly can be an exhausting and difficult exercise for a writer, especially if the stories pivot on human inadequacies, suffering and violence. Mauritius-born writer Ananda Devi is widely acclaimed for her profound understanding of the undesirable side of the human psyche. Known for her sensual prose and startling images, Devi’s characters chart a course of their own in tales that do not necessarily have happy endings. “I always go towards ambiguous characters, because that’s what human beings are, not black or white but in innumerable shades where the same character can be courageous and cowardly, loving and hateful, generous and cruel,” observes the 60 year-old writer.

Interestingly, her writing skills got noticed at a rather young age when she won a short story competition organised by French television, open to all Francophone countries. At 19, she published her first collection of short stories. Since then, she has authored 11 novels. Her latest, Eve Out of Her Ruins (Speaking Tree; ₹ 299; 174 pages), is poignant. Translated from French by Jeffrey Zuckerman, the story revolves around the lives of four young Mauritians compelled to survive poverty and squalor on a ‘paradise’ island that perpetuates hate and violence. Through a morbid yet engaging story, Devi unveils the ghastly reality of those “who do not belong”; unfortunately hemmed away under the mesmerising beauty of one of the world’s most popular tourist destinations: Mauritius. Awarded the prestigious Prix des Cinq Continents for the best book written in French outside the country, Eve Out of Her Ruins is already a prescribed text in some universities in France and Mauritius.

Translated into several languages, Devi is the recipient of numerous awards including the French state honour, Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres (2010), and Prix du Reyonnement de la Langue et de la Litterature Francaise (2014). In an email interview to Suparna-Saraswati Puri, the multilingual author, who lives in a small town on the French-Swiss border, talks all things literary, including dark narratives, gender discourse and translations. Excerpts:

You seem comfortable with intense and seemingly dark narratives.

I have had, since my childhood (and despite having had a very happy childhood with gentle and supportive parents), a kind of contemplative and questioning outlook upon the world. I have always felt that I was an observer on the edges, teetering in front of a darkness that seemed to grow out of human tragedies, especially those of individuals who were rarely heard. As I grew up, and as my writing grew up with me, I became more fascinated with the origins of violence, trying to understand where this human paradox—the possibility of immense generosity and of abominable cruelty—comes from. From novel to novel, I have pursued this thread as if it were Ariadne’s thread in the labyrinth, leading towards the Minotaur rather than away from it.

Is there a bedrock of emotions that surfaces every time you create your women characters?

As a writer, I delve into this bedrock of emotions because they are a prerequisite for my becoming fully immersed and engaged in a story. It so happens that it is women who are the most marginalised even among the marginalised, and this exploration has thus led me towards complex characters such as Eve, who is both sinned against and sinning, to quote Shakespeare, although I wouldn’t use such moralistically charged words in this context where survival means you are prepared to go beyond morals. I like to toggle with the full gamut of human emotions and passions. But I also want my female characters to go beyond all the barriers and walls that enclose them, including their bodies, and repossess who they are, without counting on any external help, be it man or divine intervention.

What are your views on the existing gender discourse in recent Indian English writing?

There has been so much exciting writing coming out in recent years, as well as in not so recent years, that it would be difficult to summarise or isolate a few. Recently, I read an autobiographical text by Meena Alexander entitled Fault Lines (first published in 1993 and republished in 2003) that I found absolutely superb, encompassing the experience of a child and young woman going from India to Sudan to the US with an absolute, raw and poetic honesty. I also loved A Restless Wind by Shahrukh Husain, a novel that moves between the UK and India and has a strong female protagonist as well as a range of wonderful female characters, and at the core of which is the quest for identity—if such an identity exists. There is obviously a very large number of books that come out in India every year and that, I am sure, explore perhaps even more unflinchingly the condition of women. There is a certain fearlessness in some of the younger writers. I hope they get recognised in the West.

Is feminism an overrated element in contemporary literature? Do you identify yourself as a feminist writer?

When I was in my 30s, I recused the term ‘feminist’ because I did not like the pejorative connotations of the word, and was against any kind of label appended to my name as a writer. However, over the past decades, I’ve come to terms with this because I realised that feminism wasn’t a label but a commitment that women are still among the most downtrodden in the world, that violence is still directed towards them even more than towards men.

So, yes, I am a feminist because I believe that we have something to say to the world that is different and might provide solutions to the disasters we are facing. And by this, I don’t mean that we need to take on ‘manly’ attributes, as too often successful women have had to do, whether in politics or business. I believe female artists have a way of looking on the world, a Weltanschauung, that can change the position of women in the world. It is paradoxical because I don’t want to be categorised as a female writer—a writer is a writer, without labels—but, at the same time, I feel I have something to say about women and from their point of view that is necessary, because the battle is not won. Far from it: men haven’t changed.

The issue of rape in India that came to a head a couple of years ago is still as frightful and urgent now as it was in the past centuries. The way women are seen everywhere as being somehow responsible for attracting this kind of violence is something that fills me with rage and a kind of boiling impotence. How can this be changed? What can we do to modify men’s way of looking at women’s bodies? In Eve Out of Her Ruins, Eve says that men take possession of her body even before they’ve touched her, just by looking at her. The answer is not to hide this body, but to change the look.

How does your distant connection with India contribute to your distinct style of writing?

Strangely enough, it isn’t that distant. For all people of the diaspora, the cultural presence of India is both vivid and at the same time a source of strangeness. All immigrants feel displaced and need to hang on to a past identity. The problem is that they also have to build a new identity. I must say that I have no problem with having multiple identities. I believe it’s the only way to avoid fanaticism and fundamentalism: being aware that we have different identities and that none of them justifies killing others.

I acknowledge the richness of my Indian origins, but also that of the African culture that came to me through proximity with the continent and the European culture that I acquired through my education. My Indian ancestry manifests itself mostly in the way I write through the symbolism, the mythical aspects, the need to ground everything I write into a larger story. It’s been immensely enriching to be able to draw from these sources.

How was the experience of writing Eve Out of Her Ruins a departure from earlier novels?

It was a little different in that it started out as a long poem. I had the idea of the title and it sounded like a line of poetry, so I thought I would write something about this girl limping in the ruins of a city at night, but then I began to see it as a story that I wanted to elucidate: who was this girl, why was she limping, why was the city in ruins? And the name Eve obviously has mythical connotations that made me want to tell a story of a ‘fall’, but where the fall is what makes this young woman stand tall and find her own self. She is by no means fallen. She is a heroine of a Greek tragedy, bringing about by her own acts the circumstances that will lead to disaster. This is very much in line with my other novels, but this one struck a chord with readers because it deals with such a contemporary issue, the tragedy of disenfranchised youth.

Was it cathartic?

All my novels take a toll on me because of their content, density and inner violence. I loved these young characters and was heartbroken to have such a bleak ending. I have tried to go inside their head and heart and subconscious to extract their strength, their fragility, their rebelliousness, their anger.

As someone who has done translations, what do you think is the most arduous part of translating?

I absolutely love the craft of translation. It is essential in making literature cross the frontiers of language, but it has long been seen as the poor sister, the Cinderella of writing. I think that a good translator is a good writer and should be recognised as such. As we become more and more aware of the intricacies and complexities involved, we justifiably give more importance to this art and acknowledge the fact that without it, so many great works would have been inaccessible to us.

The main difficulty is to find the voice of the original author and to render it in another language in a way that reads naturally and fluidly. I often tell my translators to allow themselves to take some liberties with my texts in order to make the translated text read more naturally and idiomatically. I am on the jury for several literary competitions, including one for work in translation, and when I read a book that has been well translated, it is an absolute pleasure, whereas when you feel a text is translated, it means it isn’t a good translation. This is why many classical texts are now being retranslated, in order to bring to them this new way of looking at translation.

When not writing, how do you indulge yourself?

I love watching movies, particularly thrillers and science fiction. However, I still look for movies with good screenplays and I don’t enjoy blockbusters that are too formulaic. I recently watched a science-fiction movie with a marvellous screenplay, The Arrival, based on a short story. So, basically, I enjoy intelligent and entertaining movies.

Do awards pressurise you?

Awards are a welcome recognition of my work, of course, but they are not something for which I strive. Maybe I would have welcomed them more in my early writing years, but with four decades of writing behind me, I am more interested in creating an oeuvre, something that will last and live long after I am gone. For this reason, every new work I embark on has to push me beyond my own boundaries, beyond my limits. I love playing with style, with form, as much as dealing with subjects that are harsh and that will lead the reader towards an uncomfortable place. When readers tell me they had to stop reading one of my novels just in order to take a breath because it felt as if they were being pulled into an abyss, I feel as if I have succeeded in pushing these boundaries further away. Once a reader in France came to me at a festival and said: “I am Pagli!”… Pagli is the title of one of my novels and I felt she had completely inhabited the novel, had become an intimate part of it. These reactions mean more to me than awards. Admittedly, receiving the second highest honour from Mauritius and a decoration from France did make me proud, especially when I think of my parents, who had three daughters and who did everything to allow their daughters to blossom intellectually and artistically. All these awards make me think of them with great pride and love, although they are no longer here to witness them.

Photo: Melania Avanzato Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine January 2018

you may also like to read

-

Cracking the longevity code

Small yet impactful choices can be game-changers, writes Srirekha Pillai At 102, there’s no stopping Chandigarh-based Man Kaur, the world’s….

-

Home, not alone

While a regulatory framework is vital for senior-care facilities, the need of the hour is to develop an ecosystem to….

-

Birthday Girl

Published in a special edition to honour Japanese master storyteller Haruki Murakami’s 70th birthday, Birthday Girl (Penguin; Rs 100; 42….

-

A huge treat for music lovers

Published as the revised and updated second edition, Incomparable Sachin Dev Burman (Blue Pencil; Rs. 599; 470 pages) the authoritative….