Etcetera

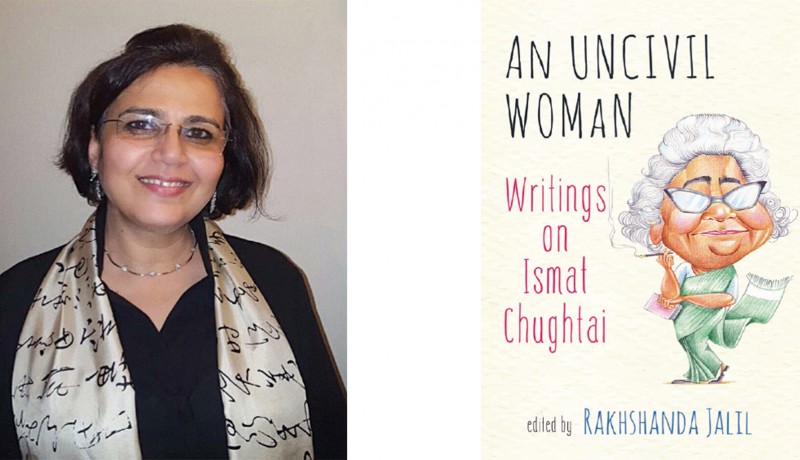

Known for her prolific writing, Rakshanda Jalil is a litterateur of eminence. As a critic and literary historian, her body of work, particularly on Urdu literature, is impressive. Her doctoral thesis on ‘Progressive Writers’ Movement as Reflected in Urdu Literature’, published by Oxford University Press as Liking Progress, Loving Change, is acknowledged as seminal research. Best known for her book on Delhi’s lesser-known monuments, Invisible City: The Hidden Monuments of India, Jalil was honoured with the Kaifi Azmi Award for her contribution to Urdu literature in 2016 and the First Jawad Memorial Urdu-English Translation Award in 2017.

It’s apparent where her love of books stems from. “My father was a doctor; my mother retired as the librarian of the school I studied in. She still reads more books than I do!” says Jalil, who has authored more than 20 books. “Books figured prominently in our lives. My brother and two sisters are all avid readers; what’s more, all of them write and are published authors.”

Jalil was also co-editor of Third Frame, a journal devoted to literature, culture and society brought out by Cambridge University Press from 2007 to 2009. Her biography of feminist Urdu writer Rashid Jahan, A Rebel and Her Cause, is a bestseller. Among Jalil’s translations are The Temple and the Mosque, based on the short stories of Premchand, and Naked Voices and other Stories, based on Saadat Hasan Manto’s works. And her translation of Intizar Husain’s novel Aage Samandar Hai as The Sea Lies Ahead won the German Embassy-Karachi Lit Fest Pakistan Peace Prize in 2016.

Jalil’s recent works include Footprints on the Zero Line: Writings on the Partition, a translation of short stories and poems by Gulzar; The Traitor, a translation of Krishan Chandar’s novel Ghaddar; and An Uncivil Woman: Writings on Ismat Chughtai. At present, she is working on a critical biography of Urdu poet Shahryar. In an email interview with Suparna-Saraswati Puri, the 55 year-old, who is the founder of Hindustani Awaaz, a platform that promotes Hindi-Urdu tehzeeb, talks about her passion for Urdu. Excerpts:

What drew you to Ismat Chughtai?

I had read Ismat in dribs and drabs over the years, both in Urdu and in excellent English translations by Tahira Naqvi. More than anything else, I was drawn by Ismat’s clever use of language. Here was a language I had heard being used by my grandmother and an assortment of older female relatives in towns and hamlets across western Uttar Pradesh; it was a living language for me. To read it in a book, coming from the mouth of characters who seemed real and believable, made the stories come alive in a very special way. The language—idiomatic, flavoursome, pungent, vigorous—and those characters, so lifelike and rooted in reality, combined to create a world I could identify with. At the same time, even though her stories seemed located in a certain time and place, they spoke of universal concerns. No matter how whimsical she painted her characters, her concern seemed to be with those values that transcend time and space.

As one writer to another, has Chughtai been intimidating or intriguing?

I must be honest here: Ismat is not a terribly nuanced writer. In many ways, she is an open book; you can read her at a gallop or you can read her slowly but it isn’t as though you will derive more from her from subsequent or leisurely readings. She is what she is; she calls a spade a spade. So, frankly, while I may enjoy reading and rereading a particular story again after a gap of many years, it isn’t as though the story will reveal itself to me in a new light each time.

While compiling An Uncivil Woman, what was of crucial significance to you as an editor?

I wanted to go beyond hagiographical accounts. I wanted a warts-and-all critical study of a writer who is an important contemporary writer, one who has cast a long shadow and influenced many younger writers. Such a critical reading of Ismat seemed to be woefully lacking. Now that Ismat is being taught at the undergraduate level in many universities and colleges—both in departments of modern Indian languages and centres of gender studies—it seemed imperative that we provide students with some reference material. A brief translator’s introduction can no longer suffice. In Urdu, too, serious, scholarly studies on Ismat are virtually absent. Most literary commentators agree that Ismat is an important writer; no one tells us why and how. An Uncivil Woman was put together as a tribute to Ismat in her centenary year and to fill a gap.

Do you feel Chughtai’s voice as a writer needs to be heard today more than ever before?

Clearly, Ismat’s voice needs to be heard because the values she stands for are still important and relevant: gender justice, anti-fascism, democratic values, secularism, etc.

How was the experience of putting together An Uncivil Woman vis-à-vis A Rebel and Her Cause, which is on the life and work of Rashid Jahan?

My biography of Rashid Jahan was a labour of love; it was a book I needed to write. I wanted to share my great joy and admiration for such an exceptional human being with a wider audience. The book was a biography that included translations of some of her stories and plays. In the biographical part, I wanted to trace her family background, her exceptional, visionary parents who founded a girls’ school at Aligarh, her attraction towards communism and decision to join the Communist Party of India, her work as a doctor and later as a founder-member of the Progressive Writers’ Association (PWA) and the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA). The Ismat book, in a sense, came from this. All through A Rebel and Her Cause I was referring to Ismat and her many anecdotes about Rashid Jahan, about how the latter influenced Ismat. But I must point out, An Uncivil Woman is an edited volume; I have commissioned essays and translations from different contributors. In that sense, it is not my work alone.

Tell us about Hindustani Awaaz. How do you balance your time between organisational work and writing?

Like many other things in my life, Hindustani Awaaz is a labour of love. The impulse behind it is sheer jazba, the desire to make a difference, no matter how small. Hindustani Awaaz is about content, not numbers. Launched in 2003, it is an organisation dedicated to the promotion of Hindustani literature and its rich oral tradition. It seeks to publish, position and popularise various elements culled from the different genres of Urdu and Hindi language and literature. In the broadest sense, it endeavours to provide a platform for scholarly and non-scholarly views and voices in Hindustani on Hindustani. In doing so, it also seeks to showcase the rich pluralistic heritage of India that is also known as Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb.

Yes, it is a challenge to find a balance between running Hindustani Awaaz, which incidentally I do all on my own—from conceptualising events, finding venues/partners, designing e-invites and posters, sending invites on email, WhatsApp and Facebook, handling media and publicity. So, yes, I am proud to say I am a one-woman army and it does take its toll. But then one learns to multitask!

What do you like to do when not writing?

I love gardening; I enjoy growing my own vegetables. And travelling, for work or pleasure, is a great stimulus.

Tell us about your family.

My grandfather was a poet, a literary critic and teacher. I am happy to say I am passing on the same ‘germs’ to my two daughters—both love to read and write, so much so that the younger one has turned the walls of her room into a huge scrapbook covered with handwritten lines of poetry and quotations from all her favourite writers.

Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine April 2018

you may also like to read

-

Cracking the longevity code

Small yet impactful choices can be game-changers, writes Srirekha Pillai At 102, there’s no stopping Chandigarh-based Man Kaur, the world’s….

-

Home, not alone

While a regulatory framework is vital for senior-care facilities, the need of the hour is to develop an ecosystem to….

-

Birthday Girl

Published in a special edition to honour Japanese master storyteller Haruki Murakami’s 70th birthday, Birthday Girl (Penguin; Rs 100; 42….

-

A huge treat for music lovers

Published as the revised and updated second edition, Incomparable Sachin Dev Burman (Blue Pencil; Rs. 599; 470 pages) the authoritative….