Etcetera

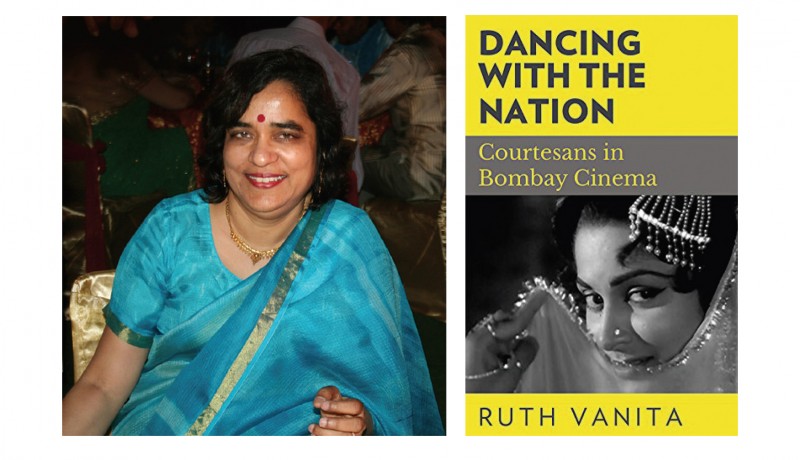

Reading Ruth Vanita’s latest title Dancing With The Nation: Courtesans in Bombay Cinema inadvertently brings to mind Mahasweta Devi’s quote: “Indian culture is a tapestry of many weaves, many threads. The weaving is endless as are the shades of the pattern. Somewhere dark, somewhere light.”

Given that Hindi films constitute an integral part of everything that is casually termed Indian, the book is truly fascinating and insightful. Although, as Vanita clarifies in the introduction, “My book is not primarily a film studies work.” The intensely researched work examines gender and sexuality through a stratum of courtesans. Though socially ostracised, courtesans, according to historical records, were considered custodians of etiquette (naffassat). In Dancing With The Nation, the author’s study of over 250 Hindi films spanning 1930s to the present highlights a little known fact: courtesans emerge as the first group of single, working women showcased in South Asian cinema.

Prior to teaching South and Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Montana, Vanita taught at Delhi University. She is known for her specialisation in British and Indian literary history with a focus on gender and sexuality studies. She is also the co-founder of Manushi, India’s first feminist magazine. Some of her better known titles include Gender, Sex and the City: Urdu Rekhti Poetry in India 1780-1870; Love’s Rite: Same-Sex Marriage in India and the West; and Gandhi’s Tiger and Sita’s Smile: Essays of Gender, Sexuality and Culture. In addition, Vanita has translated works of writers such as Premchand, Rajendra Yadav and Mannu Bhandari. In an email interview with Suparna-Saraswati Puri, she talks about modernism of courtesans and the vast Indian heritage of erotic art, literature and thought. Excerpts:

How is Dancing With The Nation different from your other books?

All my earlier books were on written literature—poetry and fiction in different languages. This is my first book on cinema, though I have been writing film reviews for decades. I wrote this book for everybody who enjoys watching Hindi movies. I wanted to write about movies other than the over-examined Umrao Jaan and Pakeezah. So I watched lots of movies, right from Aadmi (1939) and Raj Nartaki (1941). I was excited to watch so many heroine-centred movies from every decade, with courtesans often being the heroines. What was pivotal to me was recognising the way the lives of real-life tawaif, many of whom were directors, producers, actors and singers in early films, were refracted in movies. Courtesans are the first group of single, working women in films. They are also highly independent in the modern way, owning houses and driving cars (Shair, 1949; Benazir, 1964). Some form their own alternative families by adopting sisters (Sunny, 1994), brothers (Gomti Ke Kinare, 1972; Dream Girl, 1977) and children (Amar Prem, 1972). Most courtesans on screen are shown living a hybrid Hindu-Muslim lifestyle.

What were the challenges while working on the book?

Some old films were hard to find. I posted queries on Facebook and received helpful replies. YouTube was invaluable. Finding the right stills from old films to use in the book and finding the right cover picture were difficult. I was very lucky that Priya Dutt kindly gave permission to use the picture of Waheedaji from Mujhe Jeene Do.

What inspires or intrigues you about sexuality, given your insightful contribution to the subject through your earlier works?

The fact that although humans often mistrust and suppress desire or kama, it manages to find myriad creative ways to express itself. This is why Kamadeva is a God and kama is one of the goals of life. As the Kamasutra playfully puts it, “Who knows when, where, why and how one does it?”

Does Dancing With The Nation provide fresh perspectives on the subject?

This book pays tribute to the way courtesans, shown in films as working women, intellectuals and artists—all of which they were in real life—bring music, dance, ideas, and the playfulness of Eros to modern Indians across all divides. Even in the films of the 1940s and ’50s, courtesans make their own choices regarding whom they want to love, live with, and marry. They often take the initiative in pursuing a man. Courtesans are models for the modern ways of loving and desiring; romantic heroines incorporate many elements of courtesan eroticism into conjugal eroticism.

In India, do you think the discourse on sexuality, gender and culture outside intellectual circuits is often misconstrued, if not misunderstood?

Thanks to the puritanism of 19th century British rulers, which Indian social reformers and nationalists by and large embraced, 20th century Indians have tended to be embarrassed about our wonderful heritage of erotic literature, art and thought. Despite this, our many traditions of erotic fun, play and creativity did survive; for example, in popular film songs such as the mujra, the sarapa and funny, over-the-top songs like Jaane kahan mera jigar gaya ji. Courtesans used to perform not just romantic or mystical songs but humorous, non-mystical ones, which I studied in my 2012 book on Urdu poetry in Lucknow, titled Gender, Sex and the City. Today, many Indians are shaking off the burden of colonialism and acquiring a new self-confidence with regard to many aspects of life, including pleasure and sexuality.

How do you balance academic responsibilities and literary engagements?

I’m fortunate to be able to teach many of the subjects I am interested in and research whatever subject I want to. My research has, therefore, not remained confined to one area but has ranged widely over different cultures and topics, from the epics and Purana (I have just written an essay on male-female dialogues in the Mahabharata) to Shakespeare, from translating Hindi and Urdu poetry and fiction to the cycles of influence between Indian and European writers. I find research very pleasurable, especially working with manuscripts and forgotten texts. I had a great time watching over 250 films for this book. My partner Mona is a great support in all my work.

How frequently do you visit India?

I don’t see them as visits or trips. I see India as my home. For now, I am living both in Missoula in the US and Gurgaon. It was great to meet many old and new friends at the Delhi release of Dancing With The Nation in December.

How do you like to relax?

Chatting with friends in person or on the phone, reading for pleasure, playing with my son, listening to music, watching movies and going for walks.

Photo: Mona Bachman Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine May 2018

you may also like to read

-

Cracking the longevity code

Small yet impactful choices can be game-changers, writes Srirekha Pillai At 102, there’s no stopping Chandigarh-based Man Kaur, the world’s….

-

Home, not alone

While a regulatory framework is vital for senior-care facilities, the need of the hour is to develop an ecosystem to….

-

Birthday Girl

Published in a special edition to honour Japanese master storyteller Haruki Murakami’s 70th birthday, Birthday Girl (Penguin; Rs 100; 42….

-

A huge treat for music lovers

Published as the revised and updated second edition, Incomparable Sachin Dev Burman (Blue Pencil; Rs. 599; 470 pages) the authoritative….