People

Not far from Bengaluru, Deepa Narayanan finds Dr Prabhakar Rao reviving the biodiversity of fruits and vegetables in the hope of revolutionising agricultural practices around the world

Dr Prabhakar Rao’s produce, carefully cultivated on his farm on the outskirts of Bengaluru, reads like the fine print on a pricey menu—purple, pink and black corn with a lemony flavour; mustard leaves with a wasabi bite; and apple-shaped cucumbers that leave a hint of lemon in your mouth.

A stroll around the 2.5-acre farm, close to Kanakapura town about 30 km from Bengaluru, is an eye-opener. Thriving in different lots are about 20 varieties of mustard leaves, over 20 varieties of tomatoes, and many varieties of tulsi leaves including one that boasts a cinnamon flavour and another with a strong, camphor-like taste. As magical as these varieties appear, it makes one wonder whether these exotic-looking fruits and vegetables were created by genetic manipulation, not natural processes.

But here’s the shocker. While these varieties of herbs and vegetables look like the result of some pretty fancy cross-breeding and genetic modification, these are not hybrids. “Hybrids are contrary to what nature does. And I do not do or encourage that. What I grow on my farm is entirely indigenous,” emphasises Dr Rao, pointing to the patch of tulsi that radiates liquorice, lemon and cinnamon flavours.

The varieties flourishing on Dr Rao’s farm grow out of ‘heirloom seeds’, also called indigenous or desi seeds, which are completely natural, passed down thousands of years by a process of open-pollination, far from man’s meddling ways. In simple terms, heirloom seeds are those that grow plants exactly like the mother plant, producing more such seeds for the next season.

Jolting us out of these musings, Dr Rao, an agriculturist with a doctorate from the University of Agricultural Sciences, Bengaluru, says, “Humans took to agriculture around 10,000 years ago but thanks to industrial cultivation the creation of hybrid seeds and commercial farming, we’ve lost almost all the biodiversity in vegetables and plants in the last 100 years. And all the varieties I now grow on my farm thrived in India a long time ago, of course, in the pre-industrial age.”

When humans began farming, they were also ‘seed keepers’, traversing the seven seas and bringing back more seeds of newer vegetables. “Back then, nobody bought seeds,” explains Dr Rao. “People planted a certain vegetable, and if it grew well, it became part of the local diet, whether or not it was native to the land. For instance, except for a couple of greens and tubers indigenous to India, most of what we eat today in our country, including potatoes, comes from somewhere else.”

In the 1970s, around the time India was seeing the advent of industrial agriculture, Dr Rao was working on his PhD in agriculture. Belonging to the generation of scientists who rolled out the Green Revolution, Dr Rao also encouraged farmers to use hybrid seeds, urea, fertilisers and pesticides for industrial agriculture—all for better yield and to fortify crops from diseases.

But the era of industrial agriculture was a turning point for India, just as it was for every other country that embraced it, for it took away seed production from farmers and turned it into an industry. Seed companies created hybrids, and soon, hybrids that brought them the most profits. Now, every season, farmers needed to buy seeds from manufacturers, and they became dependent on these large corporations. “Deep inside, I remember feeling unsure whether industrial agriculture was a sustainable model for the earth,” muses Dr Rao.

Dr Rao changed his field of study to architecture and set up practice in Dubai, where he worked for over 20 years. But he was still intrigued by the loss of biodiversity in the fields and forests. While his work commitments took him to remote corners of the world, he took time there talking to older generations of farmers and collecting seeds they had once used. “That became my passion and I wanted to see how to get people to become aware of this problem, and inspire them to take forward the legacy of the ancient guild of seed keepers,” he reveals.

Then, in 2011, Dr Rao and his family decided to return to India—to his hometown, Bengaluru—for good. That’s when he chanced upon an article published in National Geographic magazine. It talked about a 1983 research study conducted by what was then called the Rural Advancement Foundation International in the US, now called the National Centre for Genetic Resources Preservation (NCGRP). The study compared the biodiversity among 10 varieties of vegetables available across the world in 1983 against those available 80 years before that, in 1903.

“The article revealed that even among these 10 vegetables, the world had lost 93 per cent of their biodiversity in merely 80 years,” explains Dr Rao. “So a hundred years ago, if you went to the market, you would find 543 varieties of cabbages, 307 varieties of sweet corn, 490 varieties of lettuce, 408 varieties of peas, 463 varieties of radishes, 408 varieties of tomatoes, and 385 varieties of cucumbers. Today, you’d be lucky to find four varieties of lettuce,” he smiles, confident that his point had hit home.

So while, earlier, all Dr Rao did was collect seeds from farmers, he now felt compelled to work full-time on his passion. His involvement in the Art of Living programme led him to become a trustee in the agricultural trust of the establishment, which gave him access to 20 lakh farmers across the country. “It was just the platform I needed to promote sustainable, chemical-free, natural farming technologies across India, especially in climate-resilient agriculture,” he says.

The agriculturist, who was invited to give a talk on the popular online platform, TEDx, titled ‘Let’s Save The Vegetables’, in December 2017, built the necessary infrastructure to test and plant the seeds he had brought back to his farm. He proceeded to conduct extensive testing of over 500 seed varieties, for genetic stability and environmental suitability.

Using certain processes to stabilise genetic varieties, his lab maintained the purity of the seed lines. Dr Rao has since stabilised around 142 rare, indigenous vegetable varieties, collected both from within the country and abroad, which can be grown successfully anywhere in India.

“My travels through India, after I got back in 2011, made me realise that in the last 30 years, farmers all over India had completely stopped making seeds. An unbelievably large percentage of vegetable seeds sold in the market were hybrids, adding to the rapid depletion of the little biodiversity left in vegetables. In fact, if in the last 100 years, we had lost 93 per cent of biodiversity in vegetables and fruits, in the last 10 years, we’d lost 99 per cent of the 7 per cent that was left,” he says.

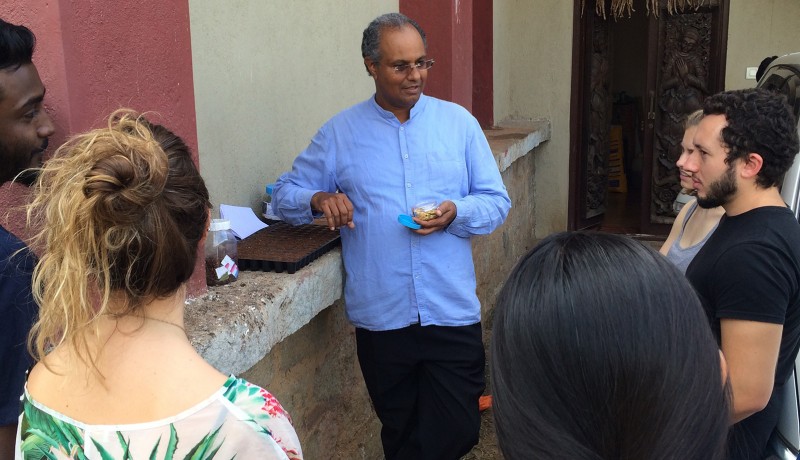

Today, to popularise heirloom seeds and the importance of sustainable agriculture and maintaining biodiversity, Dr Rao conducts workshops for families and school students on his farm, where he encourages people to taste the vegetables and greens he grows. And for those really interested, he even conducts lessons on how to care for the plants, harvest and store the seeds, and parts with recipes for delicious salads from the produce. “I decided to create a nascent guild of seed keepers, by talking to kids about the loss of biodiversity so that they would become sensitive to the losses in the field. That way, we can stem the rot and slow it to some extent,” says a hopeful Dr Rao.

The agriculturist also shares and sells his heirloom seeds with urban gardeners, kitchen gardeners and friends via his online portal www.hariyaleeseeds.com. The idea is to inspire people to become seed keepers. “People buy seeds from the farm and grow a purple variety of okhra, or a green-coloured okhra with a pink tip, take a selfie with that and post it online,” he says, excitedly. “Some of those posts have received as many as many 1,000 ‘Likes’. Then those people become influencers and are approached for the seeds, which they distribute at family gathering or parties.”

Of course, there are others who promote heirloom seeds both abroad and in India. Navdanya, a research-based initiative founded by world-renowned scientist and environmentalist Dr Vandana Shiva, for instance, is one such Indian seed savers network, comprising seed keepers and organic producers across 22 states in India. For the last two decades, the network has helped set up 122 community seed banks across the country and trained over 900,000 farmers in seed sovereignty, food sovereignty and sustainable agriculture.

Dr Rao uses some more shock therapy to encourage more and more people to embrace heirloom seeds. GMO hybrids across the world are a major threat to open-pollination agriculture. For instance, a single pollen grain from a GMO plant that possesses the Terminator Gene is enough to destroy a whole field of vegetation, thereby forcing farmers to buy GMO hybrids to produce their food, he reveals.

“What I do on my farm—collecting, conserving and reproducing heirloom seeds—is the simplest way to get these players in the market off the chain linkage. If I can connect producers to the consumer, the GMO and hybrid seed-producing companies will organically fall out of the chain. The only way to fight these companies is to bring back into the world the heirloom seeds and as much biodiversity in vegetable varieties as we can,” says Dr Rao.

Why heirloom seeds are important

| INDIGENOUS SEEDS | HYBRID SEEDS |

| Farmer can produce his own seeds | Farmer has to buy seeds from the producer every season |

| Cost of producing seeds – very low | Cost of buying seeds – very high |

| Suitable for organic farming | Suitable for chemical farming |

| Very hardy and easy to grow | Requires a lot of inputs and care |

March 2018

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….