People

Travel writer, historian, photographer and co-director of the Jaipur Literature Festival, this Scot has made Delhi his home, India his muse and the world his oyster, discovers Suparna-Saraswati Puri

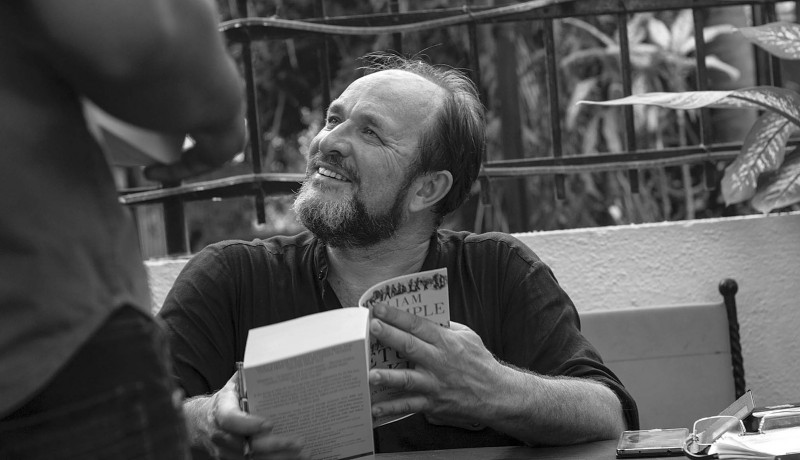

Living in a sprawling farmhouse on the outskirts of Delhi with homes in England and Scotland, “it’s a ridiculously indulged existence,” he confesses. But William ‘Will’ Dalrymple is so much more than the archetypal burrah sahib. Travel writer and historian, critic, curator and photographer, his palpable love for India and impassioned engagement with its history have won him the love and loyalty of millions of readers.

From his debut, In Xanadu: A Quest (1989), a 22 year-old’s experiential walk tracing Marco Polo’s travel from Jerusalem to Inner Mongolia, and his labour of love City of Djinns: A Year in Delhi (1994), after he moved there in 1989, to his personal favourite, From the Holy Mountain: A Journey in the Shadow of Byzantium (1997), which details “the demise of Christianity in its Middle Eastern homeland”, Dalrymple succeeded in converting his wanderlust into an art form. Then, the historian in him firmly took the wheel with the celebrated ‘East India Company’ trilogy: White Mughals (2002), “a book that took forever in terms of writing” and will be made into a film by Academy Award winner Ralph Fiennes; The Last Mughal: The Fall of a Dynasty, Delhi, 1857 (2006); and Return of a King: The First Battle for Afghanistan (2012).

Along the way, he also released Nine Lives: In Search of the Sacred in Modern India (2009) exploring varieties of religious devotion, whose release saw the Scot tour the US, UK, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Holland and Australia with some of the mystics featured in the book performing music and poetry; scripted and presented shows for British TV and radio; founded the Jaipur Literature Festival (JLF), the world’s largest free event of its kind; released a music CD, The Rough Guide to Sufi Music (2011); and curated Princes and Painters in Mughal Delhi (2012), a major exhibition for the Asia Society in New York. That’s not all. In 2016, he showcased his “first love”—photography— with the release of The Writer’s Eye, a collection of 50-odd black-and-white images without captions shot across the world over two years with a mobile phone. The book was the unintended outcome of his travels after Return of a King “from Leh to Lindisfarne, from the Hindu Kush to the Lammermuirs and across the rolling south of Sienna and the deserts of Iran, writing small stories in the dark”, as he told Forbes India last year.

This impressive oeuvre notwithstanding, Dalrymple is remarkably unassuming as he warmly welcomes us on a spring afternoon to the farmhouse he shares with his artist wife Olivia (“Oliv”) Fraser and an assortment of peacocks, pigeons, turkeys, chickens, goats and stray dogs. There’s also a large chameleon seductively parked at his feet—“What a gorgeous creature!” he exclaims. “Haven’t seen one so big, ever.” Over a delightful garden-to-table terrace lunch, he shares more about his work, from his latest book, Kohinoor: The Story of the World’s Most Infamous Diamond, to the JLF experience; his perspective on the world today; and how India has changed his life “completely”.

EXCERPTS FROM THE INTERVIEW

When did your fascination with history begin?

History has always been my consuming interest. When I was small, really small, I was fascinated by ancient history and archaeology. I was brought up in rural Scotland. My first trip to London was when I begged and screamed, threw a tantrum and begged some more to be allowed go to London to see the Trinity Carmen exhibition. And it continued to be my passion. When I was leaving school, I arranged to go and dig on an ancient Syrian site in Iraq called Tabraq. It was cancelled at the last minute; they closed it down saying it was a nest for British spies—it probably was, for all I knew! Instead, my friend was going to India so I joined him. I’m still on that year off, 30 years later. I think my gap year is the longest in recorded history!

You have said, ‘Photography for me long preceded writing. In fact, it’s in my blood.’ Tell us more.

There is a little notebook somewhere at home in Scotland, in which I wrote when I was six or seven. They sent us an essay in primary school asking what we wanted to be; I said an author and an archaeologist. But soon after, my other big passion was photography. I would go somewhere looking at ancient ruins with my parents, photograph them. I think the first prize I ever won was at an archaeological photography competition. People who knew me at school would think of me as an archaeologist who took photographs, which is not so apart from who I am now: a historian who takes photographs! My other thing was organising lectures. I used to love getting famous historians and archaeologists to come to the school and give lectures—and that’s more or less the Jaipur Litfest!

How difficult is it to take a chastening view of British imperialism, as you have done in your books?

It’s not too difficult. I think as a historian you’ve got to evaluate things as they strike you, according to your moral views. If you read about British soldiers running amok and murdering people in Delhi, you don’t hush it up. You write it straight and I think the British support that. I have never got attacked in Britain for plain speaking. But they are also very ignorant because it’s not in the school curriculum. In general, the British are brought up believing that theirs was a very benign one as far as empires go. At least not like the very horrible, racist German empire or the racist Belgian empire; everyone else’s empire was horrid. This was a widespread view. It was echoed by Andy Roberts at the Jaipur Litfest 2017 when he said, “…how you’ve been spared the horrors of French colonialism, subject to the glories of the British”. People don’t know the fine print. And they are very surprised by what they find. At least I was, initially.

You’ve just co-authored Kohinoor with Anita Anand. In view of the lawsuits filed by Indians and Pakistanis to reclaim the rock, do you think the Kohinoor is more of an emotive issue?

Well, not only Indians and Pakistanis. There are also specific claims on it by the Sikhs, who want it back at the Golden Temple… and even Iran, Afghanistan and the Taliban! So, it’s a much claimed diamond. We went into fifth gear with this book when solicitor general Ranjit Kumar made a bizarre announcement formally to the Indian Parliament in April 2016 that the Kohinoor was given to the British by Ranjit Singh as a gift and was not, therefore, loot. Now, everything about that statement is completely unhistorical. There are many, many mysteries about that diamond. It being passed from the Sikhs to the British is not a mystery; it is there in black and white in the Treaty of Lahore, Article 6, that this was part of the condition of ending the hostilities of the Second Afghan War and part of the long treaty that brought peace to Punjab under the East India Company and dissolved the government of the Khalsa. Actually, I don’t think anyone would dispute that.

So at that point, we began to realise how much heat was being generated by this diamond but no light! According to this version of events, it was this mined antiquity that entered the eye of an idol in a Kakatiya dynasty temple, passed into the wicked hands of the destroying Khiljis who lost it to the wicked idol-destroying Lodis and then the idol-destroying Tughlaqs and finally the Mughals, who lost it in a turban swap with Nadir Shah (because he hid it in his turban), who slept with a dancing girl! Not one single detail of any of that is true or has any tangible evidence to support it.

The first reference to the diamond occurs in 1750 after Nadir Shah has been assassinated and in the retrospective history of his reign by one of his soldiers, who writes very clearly and unequivocally: ‘I saw the Kohinoor; it was on top of the peacock throne attached to the heads of one of the peacocks.’ There is not a squeak of solid evidence of where the diamond was before that moment! There are references to a stone that Babur held that may be the Kohinoor but may also have been other diamonds knocking about at that time—two of the most famous, most probably originally larger than the Kohinoor, were the Daria-i-Noor, which is in Tehran, and the Orlov diamond, which everyone else has forgotten about. No one’s claiming them; they must feel very lonely! Kohinoor stole the spotlight only quite late, in 1851, with the beginnings of a legend growing around it during Ranjit Singh’s time because he singled it out for state occasions. He wears it; it becomes this symbol of sovereignty. But it only becomes the rock star everyone’s heard of in 1851.

How do you juggle different roles—historian, writer, critic, curator and photographer—with such ease?

It basically boils down to one talent, which is writing, one of the few things I can do! My career was made easy by the fact that I have very, very few talents. Unlike my children [Sam, Adam and Ibby] or wife, I am pretty ropey at languages, I haven’t got any business sense, I can’t control money and I would never manage to be a lawyer for five minutes. I am really not being sort of mock modest here. I’d be a nightmare to have in an office, any office. Something I can make a living with is writing. As a writer, you can choose what you want to write about, whether it’s a book review or a travel book or history book. And history books and travel books aren’t as different as they sound—the travel book is full of history and the history book is full of travel! I’ve got small-time photography as well. And I enjoy organising lectures and festivals and can rope in my friends to come and speak.

How was your introduction to India as a backpacker?

I had a very sheltered upbringing. My parents lived in a very beautiful part of Scotland. Their friends would come and visit them in summer; we never went anywhere as we were always entertaining. So I was very untraveled and very naïve. But I loved history and I was already used to beetling in my spare time on my bike to churches or archaeological sites, old castles, that kind of stuff. The moment I arrived in India, I was amazed. And within about two weeks, I was thinking, ‘God! I really love this place!’ I went on this long train journey right through India. I went for a job in Dehradun, which didn’t quite work out, and then continued travelling for a few months, through Agra, Delhi, Gwalior, Orcha, Khajuraho, Aurangabad, Goa, the South, all those wonderful temples. I had a budget of 35 rupees a day in those days; you could still get a room at the Archaeological Survey guesthouses and chai was for one rupee or 50 paise and a thali was often five or eight rupees. You can still get a thali for that amount at the National Archives! I had no money, which meant that you had to choose between travelling or a hotel. You didn’t eat lunch, only biscuits or a kela at bus stops. Often what we’d do is keep looking around in the day and take a night bus; so, a day wouldn’t go by without travelling.

Does it really take an outsider to show us what’s really wonderful about our country and culture?

It is not an India-specific thing. The existence of travel writing is predetermined on the fact that an outsider sees things more clearly than locals, wherever you are in the world, whoever the local is. Ibn Jubayr in Norman Sicily sees and records stuff that no normal Norman is able to see. Vikram Seth is able to see a Tibet that no Tibetan can see. If went to London, you’d see stuff I simply don’t notice.

How do you stay motivated through the long years of research each book demands?

It is important to find a subject you want to live with for three to four years. Kohinoor is a slim book and co-authored. But the big fatties—White Mughals, The Last Mughal and Return of A King—are each four, five, six-year projects and you need to be completely passionate. The challenge each time, which gets more difficult, is to find a subject you are going to be fascinated by; have something new to say about; and for which there is a market, because I am not paid by a university department. Take the book Vikram Seth wrote about his dentist uncle, Two Lives; it was nice but no one bought it. I think it was his first book after A Suitable Boy, which sold 25 million copies around the world. Two Lives sold 5,000 copies. So, however grand you are, there is no guarantee on the readership that will follow you.

Is there any particular Indian historian you enjoy reading?

Well, it’s a strange situation in India because—and this is in a sense the space I filled—you don’t have a huge body of historians writing for the general public. You have some amazing historians doing amazing research but, by and large, 99 per cent are writing for their fellow academics, in academic prose, and often with a post-colonial jargon attached. All of it is perfectly legitimate but it means your average Indian reader going into a bookshop has to choose between some pretty turgid academic work and work by popular, often foreign, writers. However, there are exceptions that are growing in number now. Obviously [Ramachandra] Guha; he writes for the academia, he writes for the general public. He has worked in the academia in the past but is now, like me, outside the ivory tower. He has got his chela in Srinath Raghavan, who is very good. There are lots of non-fiction writers coming up… Sanjeev Sanyal, Suketu Mehta, Basharat Peer, Pankaj Mishra. So it’s changing. But it is nonetheless an odd situation that you have extraordinary, complicated, fascinating history, yet you are trying to find writers that are writing cutting-edge history respected by their peers that is based on primary sources but is also well-written. Where I come from, bookshops are pretty well weighted 50-50 between fiction and non-fiction. The non-fiction bestseller list often outsells the fiction. For instance, a book like Longitude, a very clever little slice of intellectual history, sold 11 million copies, selling as much as John Grisham or Rushdie. When I arrived here, that is the vacuum I felt. Now, I think it would be much more difficult for a young Brit, Italian, American or someone coming here. They would face much more competition. There is a publishing structure that wasn’t available when I came; there was only Penguin India. Also, there weren’t any litfests when I started off.

JLF has just completed its 10th edition. How do you see the festival growing organically while retaining the original flavour?

It is a magnificent success. With 190 imitations, it is the biggest literary festival in the world; we had close to half a million this year. The problem is that it is hugely crowded. Through the five-day festival, it’s busy; on Saturday and Sunday it’s bursting, I think the solution is to open up a second venue next year during the weekend only, which would be called Jaipur Plus or JLF Plus or something. Basically, where we move some of the more pop stuff—Bollywood stars, television hosts, cricketers—into a big separate venue with a capacity of 7,000-8,000. Hopefully, that would also drain off some of the holiday-making crowds because there are lots of school kids who come just to take selfies and that sort of thing.

With Bollywood hopping on the bandwagon, can JLF claim to be purely about literature?

The original idea of promoting literature is totally intact—people come as we have the best writers inthe world there. We’ve never been snobs and always believed that there’s room for a chick-lit session. We don’t just invite a Bollywood star; there has to be a literary aspect. If Amitabh Bachchan has published an autobiography, it seems perfectly legitimate to host him. We usually only have one Bollywood superstar a year—it was Rishi Kapoor this year; Sonam Kapoor in 2016, Amitabh two years ago, Aamir Khan 10 years ago. For every one of those, we have 10 sessions on translating Punjabi Dalit poetry, which don’t get reported! Another problem is the press we get because, in reality, there are only about 10-15 full-time literary journalists in this country, like Nilanjana Roy for example. Often, you have these journalists sitting on the press terrace and smoking, having a glass of beer in the sunshine, waiting for something to happen, while actually a Nobel prize-winner is speaking or two Man Booker awardees are in conversation or the greatest voice of Urdu poetry is there!

You now have JLF extensions outside India, in Boulder, London and Melbourne. What is the purpose behind these?

This is not my initiative, it is Sanjoy’s. [Sanjoy Roy is managing director, Teamwork Arts, which organises JLF.] All four extensions are very small but it’s been nice to carry the flag to new pastures. As a founder, I am proud that JLF is an international brand. It is a serious programme in the sense that we cherry-pick the best sessions from each year and take them abroad. Also, it’s a slightly different exercise: in Jaipur, we bring the world’s greatest literature to India while showcasing Indian literature to the world. In the extensions, we are very much flying the Indian flag abroad with Indian writers and subjects and showcasing the best of our Indian programming.

Besides photography, travel and reading, what are your other interests?

When I am doing focused research on a history book, I will be reading fiction only during Christmas or the summer holidays. The rest of the year, it’s my job to be engaged with the subject, read exclusively and dedicatedly on it. Unless am reviewing a book or something, I will not be reading for pleasure. At the moment, I am back on an East India Company book that has been bubbling for a couple of years. My other great loves in life are history, travel, walking, the mountains and music. In fact, one of the best bits of doing JLF is not so much its programming of authors, who I already know and hang out with, but inviting some of my favourite musicians and organising the music stage.

Do you think age is just a number? How has life changed for you after 50?

Age is very real. I have just lost my mother. Suddenly at 51, about to be 52, I do feel things are very different. The biggest thing by a long way is the absence of the kids—two years ago, we would have had them around this table listening to the conversation. I love having my kids around and I miss them very much when they are not here. We will have one kid for half term by the end of next week but, in general, they are only there for Christmas and the summers. There is also, gradually, the reality of mortality to bear. I had a minor heart issue while I was in Italy, something that was easily sorted. So, yes, age is a very real thing. The lucky thing, though, is that as a writer you have a much longer shelf life than a rockstar or actor or musician or footballer; you are old in sport by 28!

You and your wife share a passion for India and her monuments. What else do you bond over?

Oliv and I have amazing amount in common. She shares my love of travelling, music; we have a similar aesthetic sense. We never disagree about painting the walls of the house or which pictures we can have up. You’d be hard-pressed to guess whether I chose the bedcover or she did. I am also extremely reliant on her for editing. She’s quite a brutal editor. I’m less of an assistance to her with her art. I’m partially colour-blind so she doesn’t always take everything I say terribly seriously! We do have our fair share of disagreements. She’s slightly keener on cold weather in Scotland; I’m probably keener on heat, deserts, the tropics. Some different friends. But by and large, most things come within the shared Venn diagram.

You seem to enjoy an idyllic life in your farmhouse. Do you miss it when you travel to London and Edinburgh in summer?

It is a ridiculously indulged existence. We are very lucky; both of us have careers that have so far paid our bills. It’s a perfect life. We have nine months here and then we take off in May when it gets hot and come back in September. We have a lovely house in London. We don’t own this farmhouse; it’s rented. We pay the rent for this by renting out the London house nine months a year.

Given recent developments, from Trump’s victory in the US to the vote for Brexit, do you think we are becoming increasingly insular across the globe?

I was born in the 1960s, which was the height of the rise of the Left, when Marxism seemed to be spreading throughout the Third World. The Left was triumphant. I was at university in the 1980s when in Britain, certainly, there was a swing to the Right with Mrs Thatcher, when retrenchment, hard work and entrepreneurship were the values and not free love and exotic drugs. There was a swing back to the left under Obama, and now we seem to be coming back right again. These are pendulums that swing backwards and forwards every 10 or 15 years. That said, this is different. Trump is far more nuts than any other US leader and Brexit is a catastrophe that was very much avoidable. I think it’s going to lead to the acceleration of Britain’s economic decline, which has been kind of arrested for 30 years, since Thatcher. You [India] have already overtaken us this year because of Brexit. The pound has fallen, so we are now officially behind small economies, and I would imagine that for the rest of my lifetime. Britain is still a prosperous place and a world leader in all sorts of stuff with a very high GDP per head. But I would be very surprised if Brexit does not have an extremely corrosive effect on that. I would imagine that living standards would begin to fall strongly over the next 20 years if we remain outside the EU.

In case of India, well, it led the pack in the rise of Narendra Modi. I was much more worried about the BJP when I was here as a correspondent [for The Guardian], when half my work was to cover communal riots during the rath yatra. And I saw some pretty grizzly stuff in one of those riots. And while things are far from perfect now and the RSS is resurgent, the odd lynching over beef is a much less dreadful thing compared to the stuff I was covering across India from 1989 to 1992. I’d be very surprised if India goes very far along the path of becoming a ‘Hindu Pakistan’. Liberals must remain vigilant as there are all sorts of places where freedoms are being restricted and institutions are being repressed. However, frankly, it’s less worrying than I thought it might be. We haven’t had any more Gujarats, for example.

What’s your key learning from life in India?

India has changed my life completely. I would have been a completely different person with different tastes, different knowledge if I hadn’t come to this country. I have been here for 30 years; it’s my home and it has changed everything about my life, across the board. From my religious views through to morality, perception of the world, sense of nationalism and nationality, India has radically changed me. Coming to India, choosing to live here, has unquestionably been the turning point in my life—I landed here on 26 January 1984 and my life divides in two around that date.

WORKS

- In Xanadu: A Quest (1989)

- City of Djinns: A Year in Delhi (1994)

- From the Holy Mountain: A Journey in the Shadow of Byzantium (1997)

- The Age of Kali (1998)

- White Mughals (2002)

- Begums, Thugs & White Mughals: The Journals of Fanny Parkes (2002)

- The Last Mughal: The Fall of a Dynasty, Delhi, 1857 (2006)

- Nine Lives: In Search of the Sacred in Modern India (2009)

- Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan (2012)

- The Writer’s Eye (2016)

- Kohinoor: The Story of the World’s Most Infamous Diamond (2016)

TV & RADIO

- Stones of the Raj (writer & presenter; Channel 4; 1997)

- Indian Journeys (writer & presenter; BBC; 2002)

- The Long Search (writer & presenter; Radio 4; 2002)

- Sufi Soul (writer & presenter; Channel 4; 2005)

- Love and Betrayal in India: The White Mughal (based on White Mughals; BBC; 2015)

HONOURS

1990: Yorkshire Post Best First Work Award for In Xanadu

1990: Scottish Arts Council Spring Book Award for In Xanadu

1994: Thomas Cook Travel Book Award for City of Djinns

1994: Sunday Times Young British Writer of the Year Award for City of Djinns

1997: Scottish Arts Council Autumn Book Award for From the Holy Mountain

2001: Wolfson Prize for History for White Mughals

2002: Mungo Park Medal by the Royal Scottish Geographical Society for outstanding contribution to travel literature

2002: Grierson Award for Best Documentary Series at BAFTA for TV series Stones of the Raj and Indian Journeys

2002: Sandford St Martin Prize for Religious Broadcasting for The Long Search

2003: Scottish Book of the Year Prize for White Mughals

2005: French Prix d›Astrolabe for The Age of Kali

2005: Sykes Medal from the Royal Society for Asian Affairs for contribution to understanding contemporary Islam

2007: Duff Cooper Memorial Prize for History and Biography for The Last Mughal

2007: Vodafone Crossword Book Award for best work in English non-fiction for The Last Mughal

2008: Colonel James Tod Award by Maharana Mewar Foundation for excellence in his field

2010: Asia House Award for Asian Literature for Nine Lives

2011: The Media Citizen Puraskar by the Indian Confederation of NGOs

2015: Hemingway Prize for the Italian version of Return of a King

2015: Kapuscnski Prize for Return of a King

Photo: Bikramjit Bose Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine May 2017

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….