People

Lata Mangeshkar confesses she is not keen on giving interviews. It took days of relentless pursuit by our director and publisher Dharmendra Bhandari before Indian cinema’s greatest playback singer finally agreed to give us 15 minutes for an exclusive interview. The allocated time was forgotten when she started talking–shyly at first and candidly later—and the interview lasted for more than an hour. Though the conversation was conducted over the telephone, the wires could do nothing to diminish the vitality of her presence. Rajashree Balaram remembers an ordinary day in her life that was made unforgettable by one of the most beautiful voices on earth

IN HER WORDS…

Being chosen to sing Ae mere watan ke logo still remains one of the greatest moments of my career. I was in the midst of preparations for my sister’s wedding, which was scheduled for February 1963, when the great composer C Ramchandra informed me that I was supposed to sing on Republic Day in the presence of Pandit Nehru in Delhi. I had very little time to rehearse. Initially, Asha and I were supposed to sing it together, but Asha had many work commitments in Mumbai so she couldn’t make it. I carried a tape recorder with me and practised on my flight to Delhi. After the song, when I saw Nehruji’s eyes moist with tears, I too felt very emotional.

I feel sad that I do not see much patriotism around me today. These days, our pride and faith in our country surfaces only when the Indian cricket team is in a defining match. We cheer loudly for our team—even I do—but all of it is forgotten when the match gets over. How many kids today really know enough about Indian culture and history? Even most parents take great pride if their children can speak English; it doesn’t matter if they have no clue about their mother tongue. I have nothing against English; after all, the British ruled over our country for 200 years so we cannot do without their language. And it’s a beautiful language. There are so many English words that we have appropriated as part of our vocabulary. For instance, it sounds funny saying, ‘Ek pal rukiye’ in conversational language; it somehow seems so much natural to say ‘Ek minute rukiye’. Yet, it’s inexcusable that we are losing touch with our mother tongues. Even in my family, the younger generation seems more comfortable with English. I urge all young parents to instil respect in their children for their mother tongue. Bachche mitti ke ghadhe jaise hote hain, jaise hum unhe dhaalenge woh waise banenge [Kids are like clay pots, they become what we make of them].

There’s this hilarious incident that happened when I visited Paris with my brother [singer Hridaynath Mangeshkar] and sisters, some years ago. Hridaynath saw this lovely pen at a shop and asked for its price in English. The shopkeeper refused to answer and stared at him stonily. He was so exasperated that he asked him the same question in Marathi: ‘Yha penchi kimmat kaay aahe?’ And funnily, the shopkeeper understood and stated the price! In many countries abroad, they have this innate pride in their language and they regard you with respect when you know yours. Internationally, your status as a person is not judged based on your command over English.

You may call me old-fashioned but I belong to a generation where Rama and Krishna were names uttered with great reverence and not as part of jokes. Today, we have crossed all boundaries of propriety on TV shows. We don’t even stop at reducing our deities, or legends like Tansen, to caricatures on comedy shows. A similar trend is followed in musical talent shows— which is why I don’t watch them. Kids from small towns, when they first enter the show, have this touching innocence when they sing; they have simplicity in their appearance that vanishes when they survive the first round and enter the second. They are made to look glamorous with heavy makeup and accessories, in clothes in which they look visibly awkward. The focus is more on the ability to look ‘smart’ than singing correctly. It saddens me. That’s also why I don’t agree to be a judge on their panel—for which I have been approached many times.

Even TV commercials have become blatantly sleazy. A man sprays a perfume over his body, and eight women can’t keep their hands off him, or leave their boyfriend to maul him! Aren’t we responsible for the statement we are making to our next generation through mass media? Do we really want them to grow up thinking everything is okay and acceptable? Am I ranting? [laughs]

I cannot blame contemporary music directors or singers for the music being churned out today. We don’t have stories where a mother sings a beautiful lori [lullaby] or the heroine sings a classical number. We are living in the times of the item number. Songs today are being composed and sung in a way that they can be danced to, and not necessarily enjoyed for the sentiment they express. There were peppy numbers earlier too but singers got the opportunity to sing many different kinds of songs for a film. For instance, in Mughal-e-Azam, I’ve sung 11 songs, which included a sad one, a romantic number, and a dance number; there were songs for different moods.

Today, songs have a very short shelf life. They don’t linger in our minds the way they did earlier. But then, how many movies hit a silver jubilee? In our times, even if the film flopped, the song would survive in public consciousness for years. Many of the films in which the songs were composed by Shankar Jaikishan used to cross silver jubilee. I used to tease them that the ‘S’ and ‘J’ in their names stood for ‘silver’ and ‘jubilee’.

I miss all the singers from the past—I regarded many of them as my brothers. I used to tie rakhi to Hemant Kumar and Mukesh. Whenever we sang together, we always had a great time in the studios. We rehearsed, discussed, argued, laughed, and ate together. Today when I hear a song sung in the style reminiscent of Mohammad Rafi, I miss him acutely and wish he was around to sing it. Earlier, people could discern between an Asha and a Lata, or a Rafi and a Kishore. Now people cannot instantly zero in on the singer when they hear a song. Among today’s playback singers, I like Sonu Nigam, Udit Narayan and Alka Yagnik. Sunidhi Chauhan too has her own unique style. Sadly, many of the good singers now prefer to do stage shows; we don’t get to hear them as much as we’d like to on playback.

I like listening to old songs. Some of my favourites are Rasik balma, Ajeeb dastan hain yeh, and Aayega aayega, aayega aanewala. It’s not that composers earlier didn’t experiment with different styles and techniques; they did. But they were not overly influenced by Western music the way composers are today. Our songs now don’t always reflect our unique cultural identity and musical heritage. Among the new movies, I liked watching Munnabhai MBBS, Baaghban and Lagaan. I specially loved the songs in Lagaan. A R Rahman did a wonderful job. The music and lyrics have a lovely vintage classical touch to them.

I have been fortunate enough to compose songs for a few films. In 1962, noted Marathi film director Balji Pendharkar phoned me during a crisis and told me about a film, Maratha Tituka Melvava, that he was making. He wanted Vasant Desai or Sudhir Phadke to compose for the films and they couldn’t give him dates as they were very busy. Baba, as I used to call him [Pendharkar], told me worriedly that he would be forced to shelve the film. On an impulse, I volunteered to compose. Initially Baba said, “If you go wrong, the press will lambast you and I don’t want that” [laughs]. I suggested that I would compose under a pseudonym ‘Anand Ghan’.

In the studio, we got music composer Datta Dajekar to conduct the musicians and tell everyone that the boy Anand Ghan who had composed the songs could not come for the recording and so he, Dajekar, had to conduct the songs. It was funny how we acted our way through the whole episode. Dajekar would even correct me so no one could suspect I had anything to do with it [laughs]. The film was received well and I got several awards for it. I continued that way with two other films. By the third film, the cat was out of the bag and people had figured out it was me. Later, I was approached by Hrishikesh Mukherjee to compose music for Anand. I didn’t; and I love the beautiful songs Salil Choudhary finally gave us.

I always wanted to be a classical singer. But I had familial responsibilities thrust on me by destiny at a very young age so I ended up pursuing playback singing. My father died when I was just 13. He used to tutor me whenever he found the time. I acted in a couple of films as a child artist and then got into singing full time.

So far, I have sung in 36 languages. No matter which language I am singing in, I write the lyrics in Devnagari script and refer to that. I find singing in Russian and Tamil very difficult. Years ago, I felt very happy when a Tamilian man came and complimented me on the authenticity of my diction. Just as my voice is a gift from the gods, I think my command over language is also a divine benevolence.

Besides singing, I love reading and photography. My eyesight is weakening so I don’t read as much as I used to. But I used to devour books, especially all Hindi and Marathi classics. I also enjoyed photography, but with the new digital camera, I feel it’s not as challenging any more. The manual camera teaches us how to handle light, colour and shadow sensitively. With the digicam, everything can be achieved by calibrating the camera to a certain degree.

There was a time I even enjoyed cooking a lot. I am known to make very good non-vegetarian food. Even now, my grand nephews and nieces ask me to cook. But I no longer have the patience to stand in the kitchen and grind masala [laughs]. Though I love feeding people, I am not a foodie—probably because I never really had the time to savour food between recordings. Sometimes I used to eat a packet of biscuits at five in the evening after a long day of recording. All those bad food habits have led to colitis. And no, before you ask, I do not follow a special diet to maintain my voice. I eat pickles and have cold water.

Life wasn’t easy when I was growing up. In 1942, my father died of an illness in the midst of a curfew. We could not afford to give him the best medical care then. My mother then told me that someday when I had made enough money, I should build a hospital. I did build one in 2001, the Deenanath Mangeshkar Hospital in Pune. Some things are non-negotiable there: poor people get heavy concessions; nurses and ward boys are strictly told not to accept any monetary gift from patients; and we do not keep admission formalities on hold for patients categorised as ‘police case’. I just feel sad that my mother could not see her dream come true; she died in 1995.

I don’t believe in dreaming. I prefer to make the best of what life gives me every day. And life has been very kind. Fame has brought with it a huge responsibility to live up to people’s expectations. Even today whenever I sing, I never let myself forget that. Ever.

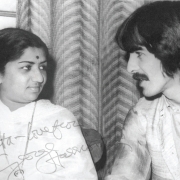

Photos: Lata Mangeshkar...in her own voice (Niyogi Books; 2009) Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine August 2011

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….