People

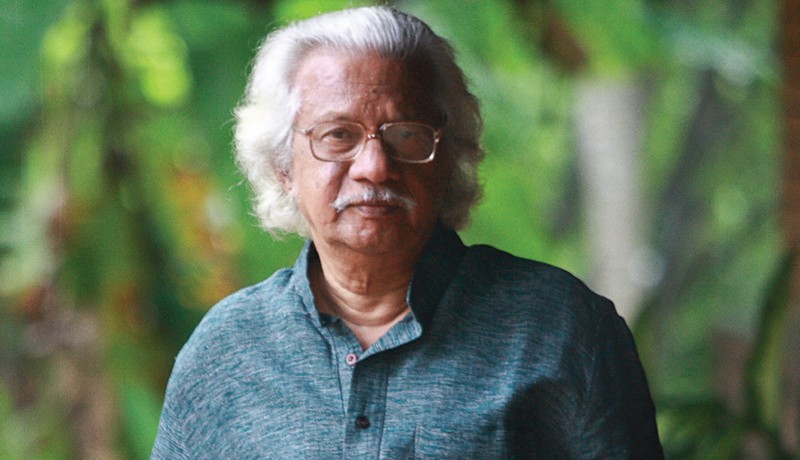

In a career spanning 38 years, Adoor Gopalakrishnan has made only 11 films—all of them have won the National Film Award in one category or the other, and been screened at film festivals across the world. India owes much of its éclat in world cinema to the director who wears his brilliance as casually as the halo of his silvery hair. Dhanya Nair Sankar meets the man who could have been a bureaucrat but chose to spend his life changing our worldview

In Sreekaryam, Thiruvananthapuram, if you ask for Darshanam, you will be politely directed towards a large compound in which stands a charming wood-and-brick house. When we approach the place, the gate is open. There is no peremptory signboard informing visitors of any guard dogs. For a man known for his reticent nature, director Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s house appears warm and welcoming.

We tiptoe around puddles in the compound, a remnant of the previous night’s downpour, and ring the doorbell. Gopalakrishnan opens the door, but instead of a smile bears a frown. He asks us how we managed to lose our way despite his precise directions to our driver. When he notices we have nothing to offer but a sheepish smile, he smiles back and waves aside the awkward moment to welcome us into his private space.

The living room is minimally yet tastefully done with simple furniture, though it’s hard to miss the abundance of magazines, books, Kathakali motifs and artefacts. The shadowed space seems to be a faithful reflection of the idealism of his youth, when his stint at Gandhigram Rural University in 1960—where he went to study economics, political science and public administration—instilled in him an appreciation for austerity.

As soon as we step inside, the rains lash out with full fury. The hall turns perceptibly darker. Yet there is a smile lighting up his face: “I love the drama of the rains.” As we talk to him, we notice that his moods are as dramatic and unpredictable as the monsoon; he is fiery while talking about contemporary Indian cinema, passionate while discussing films, stern when making a statement on cultural monopoly, and downright playful while talking about his family.

Familial bonds and memories mean a lot to him. Born in rural Pallickal and growing up in the village of Adoor, his childhood was filled with simple pleasures: playing around the large trees of mango and jackfruit; chasing squirrels; watching Kathakali; and getting drenched in the rains. The bucolic scene is far removed from the world of films. So it’s hard to say if Adoor Gopalakrishnan came to cinema or cinema came to him. By the looks of it, cinema came to him to gain some respectability.

His first film Swayamvaram (1972) is a tale of a young couple who elope from their village, aspiring for a better life in the city only to be sucked into a life of endless penny-pinching that ultimately drives them to the slums. The film portrayed the angst of post-Nehruvian times and the transition of Kerala’s middleclass into a modernist society. While some cinema aficionados squirmed at the stark portrayal of reality, one thing became clear: the film marked the arrival of a man who had no qualms shaking the underpinnings of Malayalam film aesthetics. His second feature film Kodiyettam is a heart-rending portrayal of the transition of a village simpleton from a carefree soul to a responsible family man. The movies that followed were as uncompromising in their value: Mathilukal, Vidheyan and Nizhalkkuthu. All his films have one thing in common—the protagonists are ordinary people with their flaws in place. “Flaws lend contrast and colour in the characterisation of a person,” he says. Like his protagonists, he understands the perpetual conflict between our expectations and experience.

In a career spanning over three decades, he has made 30 short films and documentaries and 11 feature films. Each film, he says, is a reflection of his experiences through life and the ensuing transformation. One can’t help but notice that his experiences come with a winning streak. Besides several national and state honours, he has been decorated with the title of The Commander of the Order of Arts and Literature by the French government in 2004. Earlier, in 2002, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington held a complete retrospective of his works. In 2005, he was felicitated with the Dadasaheb Phalke Award, and in 2006 he was conferred with India’s top civilian award, the Padma Vibhushan.

The trophies may take up significant space in his house, but they don’t occupy much room in his head. All that matters to him—and drives him to make a movie—is his conviction. He is not distracted by statistics or numbers. And though that may make him appear like an unbending man, truth be told, he is a self-confessed softie when it comes to his grandson, five year-old Tashi Norbu whose photographs adorn his walls. The mere mention of Tashi makes his eyes dance. When Tashi comes visiting, he opens up his collection of cameras (he has half a dozen) and goes on a clicking spree.

An indulgent grandfather; uncompromising filmmaker; thorough idealist; the voice of the common man; a monsoon lover. We have seen many facets to him. And it dawns on us that he will reveal his layers only if we are willing to wait and listen and observe—much like what he does with his films.

IN HIS WORDS:

I was lucky to come from a family that was passionate about art. I grew up watching Kathakali; it was an integral part of our ancestral house. We even had our own Kathakali troupe called Kaliyogam. As a child, I used to watch the performances sitting on my mother’s lap. My mother knew all the stories and could decipher the gestures accurately; my fondest memories are of her patiently explaining the nuances to women around her.

Cinema came quite accidently to me. I used to act in plays in school, and later even in college. At eight, I essayed the role of Lord Buddha in a school play. I was never an ardent fan of cinema. I could have seen a lot of films if I wanted; my uncle had a couple of theatres at Adoor, Enath and Parakkode. But I never bothered to take a look. My original plan was to join the National School of Drama but I was told the medium of instruction was Hindi. And I had no intention of producing or acting in Hindi plays. Just then, I came across an advertisement inviting applications for the screenplay writing and direction course in the Film Institute (later christened as FTII). The institute was only a year old then [in 1962]; I got the first rank and the only scholarship available that time; a princely sum of ₹ 75. And thus my tryst with cinema began. And I have loved every moment of it.

I think the Adoor who quit his government job would be happy to meet Adoor, the filmmaker. I have never regretted anything in life because I have made all my decisions with utmost conviction. Before going to Film Institute in 1962, I had a regular job in the National Sample Survey as investigator. It was interesting work as it gave me an opportunity to travel and live in remote places. The pay was good, about ₹ 400 per month. Then gradually I came to dislike the lack of dignity the job entailed. Even if I did a good job, my boss would find some fault, which irritated me. When it became a routine, I thought it was time to quit and save my self-respect. Moreover, the job was also making my theatre work difficult. I would be preparing for the production of a play when I was asked to travel to Malabar. Above all, my mother fell ill at that time and I wanted to be near her. My initial excitement of becoming an earning member of the family was all gone by then. Filmmaking seemed to be a far more endearing process.

The Film Institute was pure education in every way. It taught me a thing or two about frugal living. The meagre scholarship amount had to be supplemented with money orders from my elder brother back home. The institute had a very good library where I spent a lot of my time after classes. In the second year, Ritwik Ghatak joined as our teacher. I never met any of the teachers outside the classroom. I was also a very shy person and found it difficult to make acquaintances. When I was handed a still camera, I did not know what to shoot. And after a lot of deliberation I clicked with many apprehensions. However, the teachers liked what I had produced. During weekends I went to downtown theatres to watch old Hindi and English movies; they had special shows at half the rates. Ghatak was quite an influence; he was well-read and well-versed in Sanskrit texts like the Veda and the epics. His lectures, especially on his own films, were very inspiring. He had a great understanding of and admiration for Ray’s films.

I don’t agree with the term ‘parallel’ cinema at all. I think it was a term created by journalists to distinguish films cut off from the set formula; films that lacked big stars, song and dance. If you notice, there was nothing parallel about the cinema made by other directors who refused to conform to a formula. They too used the same distribution and exhibition channels. Of course, those who stuck to a formula didn’t have to really worry about distributors and producers unlike other filmmakers. In India we need to have different producers and distributors who are not afraid to defy the norms, or else Indian cinema will get stuck in a rut.

I don’t think my films are elitist. I have to really work hard to get the nuances right. Every time I make a film, I want more and more people, especially Malayalis, to watch it. Cinema doesn’t make any sense if it has no audience. Fortunately, I have a fairly good audience outside Kerala as well. Nobody makes films only for festivals; only those films that are aesthetically rich get selected. So it’s nice to be appreciated on such a platform.

I make cinema that enthuses me as a person, and as a filmmaker. I don’t want to simply use my skills as a craftsman to make a film; it has to be a culturally engaging experience. I look out for stories that touch a deep chord. I never give my actors a script because I don’t want to invite the danger of misinterpretation. I coach them personally to get exactly what I want.

I hope I have improved at my craft over the years. I find it very difficult to analyse myself. With each film, I’ve tried to better myself. As I have been formally trained in filmmaking, I have the ability to appreciate novel ideas in the medium and I like to try new experiments. My first film Swayamvaram had many rough edges. With time and experience, one learns to keep away the non-essentials. With experience, ideas also come from various different sources; sometimes you hear things, just observe, and you store them intuitively in your mind, not necessarily thinking about what you are going to do with them.

I think only a discerning audience can create good cinema culture. If the audience only wants melodrama and exaggeration, or confuses vulgarity for art, they lose the ability to face the realities of life. I am not really surprised that a film that deals with life as we live it attracts less audience. Any work of art especially cinema should shake you up; it shouldn’t leave you unaffected. Aesthetically and intellectually, it should stimulate you, disturb you. Not that I think that cinema can bring about a big social revolution. But it can certainly create awareness, which forms the base of any social change.

Our audience loved spectacle and mythological characters—it hasn’t changed much today. But now the spectacle is brought about by immense use of technology, and mythological characters have been replaced by larger-than-life stars. Sometimes I feel the audience only goes to see their favourite stars in extraordinary situations. For the masses, cinema remains a spectacle of improbabilities.

It is unfortunate that a certain monoculture is monopolising the cinematic world. And it’s not restricted only to cinema. ‘Small’ cultures are now increasingly made to feel as if they are inferior. Today, our children don’t know their own mother tongue, but their parents take pride in them speaking a foreign language. Exposing ourselves to other cultures is fine, but it should not inhibit us in any way; it should open us up mentally and culturally. When it comes to cinema, I think people’s expectations have gone down. They hardly get to taste meaningful cinema produced even in our own country. Unless we are exposed to a different kind of cinema, a better culture cannot evolve.

I started the Chitralekha Film Society with a few friends to promote good cinema. Well before I started my career, I realised that films didn’t enjoy any respect from the masses or classes. I became aware of the fact that the only way out was to expose our audiences, especially the young lot, to the charms of great cinema. I was motivated by my professors who often spoke about the role of film societies abroad and their commitment to spreading appreciation for cinema. Chitralekha took shape in 1964 to set up film societies, publish film literature and make quality films. Chitralekha Film Souvenir, the first ever serious publication on cinema in the language, was brought out that year. It was to make a comprehensive intervention in the film media. On the one hand, we wanted to show classics, discuss them and publish writings. On the other we wanted to distribute and produce films. For the latter, we decided to establish a studio of our own. Chitralekha’s biggest success, though, was that in just 10 years it spawned 110 film societies. We started linking cinema to the world of art and literature. And it worked—cinema started getting the respect it deserved. Even small towns started having film societies attracting newer enthusiasts.

My last two films Oru Pennum, Renda Annum and Naal Pennungal were both inspired by the works of Thakazhi Shivasankara Pillai. The last film Oru Pennum, Renda Annum was a project initiated by Doordarshan. They wanted to do a tribute to regional language writers of some standing. Thakazhi was the chosen writer from Malayalam. As I had not made any film based on short stories, I took it up as a challenge. Malayalam literature has given the world some brilliant writers. Pillai is a class apart. Another writer I admire is Vaikom Muhammad Basheer. I am attracted to any form of art and literature that makes me sit up and think about life, and reveals new and fascinating insights into life.

Oru Pennum, Renda Annum is not a sequel to Naal Pennungal as the popular perception goes. The English title of Oru Pennum Renda Annum is A Climate for Crime. It was a sheer accident that both revolved around the plight of women but the last one is more about the small crimes committed during famine and scarcity. It’s based in Kuttanad, the rice bowl of Travancore in the 1940s.

Most of my characters are common people. I like to root my characters in reality because we are all tortured by our thoughts. My prototypes are real people with real issues, not imagined or fake ones. For instance, Nizhalkkuthu was born after I read a newspaper report about the oldest hangman in Kerala.

Contemporary issues don’t really intrigue me while making movies. What is a contemporary issue? In Malayalam, all filmmakers seem to be doing it; it’s like a newspaper report or endorsement. I like to make movies of lasting human emotions and experiences so that they can be fresh even tomorrow. Any good film has to survive the period of its making.

Most commercial filmmakers think the more distanced they are from reality the better, as more people will come to watch their films. Cinema can make you better equipped to deal with life’s realities. Today commercial cinema in Kerala is blindly copying from Tamil films. In fact, Kamal Hassan recently said that once people used to look at Malayalam cinema for inspiration, not anymore.

It’s not the name of the filmmaker that attracts me but the story and its treatment. A film has to talk to me, and it should do that interestingly. There is no one director I admire; there are many. Sometimes, even big names disappoint you. I respect Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky and Japanese filmmakers Yasujiro Ozu and Akira Kurosawa. These directors engaged the audiences deeply in what they were trying to communicate. Closer home, I respect Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Ritwik Ghatak, Shyam Benegal and among the young directors, I like Girish Kasaravalli’s work.

At 70, I feel I have more enthusiasm for cinema and life. Age is the best teacher. I am able to deal with both failure and praise with equanimity. I have realised that while failure isn’t a nice thing it’s only a temporary setback. I am also very aware of undue praise from anyone and stay away from such people.

Even after all these years the grind doesn’t bore me. I do travel, but not a too much. I can’t choose my favourite country but I like Thailand and Sri Lanka. I feel very much at home in these countries. The people are very warm and hospitable and even the food is a lot like ours. I like meeting new people and learning about different cultures. Though giving too many interviews can get taxing, I look forward to them if the interviewer knows the subject. When I attend film festivals, I look forward to interacting with other filmmakers and enthusiasts.

I miss my venerated big brother M F Husain. Husain saab was very affectionate towards me; he used to like my work. Once I had gone to Hyderabad where he wanted to screen my film Nizhalkkuthu

He had invited a few friends over for the screening. After the screening, when he discussed every detail of the film with them, I felt really happy. Next day, to my great surprise, the 90 year-old Husain saab was at my hotel to take me to the airport at 4 am. I wondered if I really deserved so much affection.

I am glad to be surrounded by a lovely family. My late mother Gauri Kunjamma and my wife Sunanda have been my greatest support. I bounce ideas off my wife and, even after so many years she listens to them ‘patiently’! My daughter Aswathi Dorje is an IPS officer. My son-in-law Dr Chhering Dorje, also an IPS officer, is a Buddhist. They have a five year-old son Tashi Norbu, which means Dear and Precious—which he is to me.

I have no regrets in life, whether it was leaving the government job, or making the cinema that I do, or having made only 11. I have been totally convinced about everything I have done. I don’t go by people’s expectations; only I need to be sure of my moves. I don’t make any compromises in my profession. But I am not a rebel either. I have used the same system for my films. It’s just that I don’t feel the compulsion to do what others do.

FILMOGRAPHY

Swayamvaram 1972

Kodiyettam 1977

Elippathayam 1981

Mukhamukham 1984

Anantarm 1987

Mathilukal 1990

Vidheyan 1993

Kathapurushan 1995

Nizhalkkuthu 2002

Naalu Pennungal 2007

Oru Pennum Renda Annum 2008

Photo: Sivaram V Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine July 2011

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….