People

Shailesh Gandhi is not only a whistleblower to a corrupt government administration but inspiring a generation of RTI activists to take the battle forward, writes Shail Desai.

Shailesh Gandhi is the public face of citizens’ power in India, a man who fearlessly brought many a crooked politician, bureaucrat and government servant to book. More important, he has proved to nameless, faceless citizens that information is power, and inspired them to join the ‘revolution’ ushered in by one of the most powerful tools ever given to the common man: the Right To Information Act (RTI).

Gandhi’s foray into public service took place soon after the RTI Act was introduced in Maharashtra 13 years ago. But what makes his decision to become an RTI crusader even sweeter was that it was a deliberate choice. It was not Gandhi’s first calling but one he discovered thanks to a chance comment made by a former faculty member at an alumni meet, reveals the 68 year-old, Mumbai-based RTI pioneer.

Gandhi became an activist at the age of 55. It was the culmination of a series of serendipitous events that brought him to this juncture. When he was very young, he dreamt of becoming a lawyer. However, coming from a family of engineers and doctors, whose impression of a lawyer was a man in a black coat chasing potential clients outside a court, it was not to be.

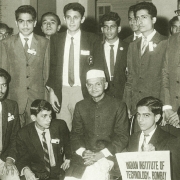

After his schooling, he acquired a degree in civil engineering from the Indian Institute of Technology – Bombay (IIT-B). Even that happened quite by chance. “I was to opt for mechanical engineering but the idea of starting my own enterprise always appealed to me,” recalls Gandhi. “Somebody told me that if I pursued civil engineering, I could get into the contracting business with an investment of ₹ 10,000-20,000. So I jumped right in.”

Those were times when banks were nationalised and they offered schemes with zero margins for young engineers. On graduation, in 1969, Gandhi had made enough money in the contracting business but he found it “rather slow”. So he took a loan and set up a factory to manufacture plastic bottles and caps—and soon made it big in the business.

However, doing something that was socially relevant was always on his mind, a thought that was reaffirmed a good 30 years later. “At an IIT-B alumni meet in 1998, I met a faculty member who casually reminded me how critical I was of society at the age of 20, when I was in college. He asked me whether I had made anything of that. I was around 50 years old then and I didn’t feel India was much better. It triggered a cascade of thoughts again and I decided to do my bit.”

Gandhi had to wait five years before he could actually embark on this course-correction. In 2003, he sold his business and got together with like-minded folks who wanted to bring about change. He had learnt of the newly promulgated RTI Act, which had been introduced in Maharashtra the same year, and also found his first assignment!

“I met former police officer Y P Singh, who mentioned a major racket when it came to police transfers. That set the ball rolling for me,” says Gandhi, whose name subsequently went on to become synonymous with the RTI Act.

The following day, Gandhi sent an assistant to procure a copy of the RTI Act, studied it and soon filed his first application. He asked the Public Information Officer of the Police Commissioner of Mumbai for the names of political leaders who had recommended police transfers. “I was refused initially but I got the information after six to eight months,” he says. “It made a small difference, at least for a while, and opened up a new world for me.”

The budding activist soon began to realise just how explosive a tool the RTI Act could be when used appropriately by common citizens. He began to understand how the Act worked, its potential to monitor the government’s functioning and expose corruption, and its ability to empower regular folk to become change-makers. These were exciting times as the RTI landscape was just beginning to take shape. Gandhi worked quickly, collaborated with other RTI activists and even became a part of drafting the national RTI Act. What followed was a full-time shift to social work.

Encouraged by the sheer power of the legislation and buoyed by the momentum he had built, Gandhi battled the mighty without fear or favour. He took on the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation, state and central governments, elected representatives and government officials, as well as conducted RTI workshops for citizens’ groups interested in learning how to effectively use this tool. Alongside his work as an activist, he also groomed other RTI activists so they could take the battle against corruption forward.

Asked to name some of his memorable cases, Gandhi points to the Crawford Market redevelopment plan where, thanks to his RTI application in 2007, he saved ₹ 1,000 crore of the taxpayers’ money and preserved the heritage structure. Then, there was the case of Police Inspector Prakash Avare of the Mumbai Police, who had been accused of raping a minor in 2004 but had been reinstated in the force the following year. After applying for a copy of the letter that had reinstated Avare, Gandhi received a reply from the Mumbai Police, saying the cop had been dismissed from service. He also names the case where his RTI application exposed Maharashtra minister Swarup Singh Naik, who had taken the medical route to avoid a jail term in 2006.

Gandhi had thus thrown down the gauntlet more times that he cared to count, and received wide recognition for his work. Then, in 2008, destiny had a bigger role for him—and it came with an ironic twist. He was appointed as a Central Information Commissioner (CIC), an appointment he is critical about to date!

“The law states that a CIC must be elected in consultation with the prime minister, the leader of the Opposition and a minister of the Union Government,” he explains. “But appointments to this post have always been arbitrary, based on political patronage rather than a merit-based selection process. We had forwarded four names of our own citizen candidates, along with recommendation letters and sent them out without expecting anything to really happen.”

Of the four names, one was that of R B Sreekumar, Director General of Police during the Gujarat riots, who had then voiced his opinion against the Narendra Modi-led government. He was instantly rejected as a candidate the night before the names were to be declared. Much to his surprise, Gandhi found that his name had suddenly been recommended!

“It was a random occurrence, more to do with blocking someone rather than choosing the right candidate. They called up a businessman from Mumbai to ask about me. Although he had never met me, he had followed my work through the newspapers. He recommended me, I received a call from Prithviraj Chavan (then Minister of State in the Department of Personnel and Training, Government of India), and that’s how I was selected,” says a still-incredulous Gandhi.

Ironically, the seemingly whimsical and arbitrary nature of his appointment typified everything that was wrong with governance in India—and the biggest weakness in the system set up to support the RTI Act. “I could have been a complete idiot. Nobody up there knew me, yet I was selected for this post. This is a deeper problem, for RTI and most of our governments. Some say I did not deserve to be commissioner but the truth is that there is no real process in place anyway.”

Extending the same logic to other statutory watchdog bodies, Gandhi points out that there are no criteria to fill top positions in the National Commission for Minorities, National Human Rights Commission and Lok Ayukta. “These are our checks when it comes to the balance of democracy but as the right people aren’t a part of it, they don’t work,” he rues. “As a result, the nation lands up spending a lot of money without actually getting anything out of it.”

In his role as a CIC, Gandhi delivered a number of landmark orders. Satyananda Mishra, who also worked as a CIC, says his colleague’s appointment was like a breath of fresh air in the commission. “He was the first non-civil servant to be appointed and he brought in a different dimension to the whole place,” he affirms. “He believes transparency is supreme and is a very passionate person. His commitment to RTI is unmatched.”

Among Gandhi’s most crucial work during his stint as CIC was to direct the Reserve Bank of India and other banks to disclose information under the RTI Act, something they had stubbornly refused to do up until then. It was an uphill battle but one that ended in eventual triumph. In December last year, the Supreme Court upheld 11 orders delivered by Gandhi, a landmark judgement in terms of transparency and accountability in government functioning. “I think it was one of the high points of my career because I was often criticised for being an activist and for having little idea of how the government functions,” says Gandhi, who has received numerous awards for his colossal body of work.

In a lighter vein, he recounts one of his most unusual RTI requests. “The Public Information Officer (PIO) once came to me and insisted that I look at a query. Someone who was dissatisfied with my decision had put in another query—to find out ‘how much bribe has Shailesh Gandhi collected in the last few years?’ I asked the PIO if we had any records on this and he looked back at me in amazement, asking how that was possible. So I told him to reply, saying there was nothing on record; it was the truth!”

Gandhi also focused on clearing the backlog that had accumulated before he joined office, having had a good understanding of it during his days as an activist. “My team of volunteers would sit during hearings, analyse what had actually happened during these hearings and how much time it took to clear a particular query. We then came out with a report on our findings.”

While most commissioners across the country disposed of 1,500-2,000 cases every year, Gandhi proved it was possible to clear at least 4,000 cases. “My average each year was about 5,400 cases and, in the last year, 6,000 cases,” he reveals. “It is possible to address 7,000 to 8,000 cases each year. The delay is negatively impacting the RTI movement.”

Although the tenure of a CIC is five years, Gandhi retired prematurely in 2012 after serving for three years and nine months as he had reached the retirement age of 65. During this time, he also received his fair share of criticism, which he took in his stride. “In his hurry to speed up case disposal and clear the backlog, he at times refused to hear a complete plea. He always had the public’s interest at heart but his approach could sometimes be very frustrating,” says Krishnaraj Rao, a Mumbai-based RTI activist, who credits Gandhi with grooming activists like him during the early days.

On his return to Mumbai, Gandhi resumed work as an activist but is now selective about the issues he takes up. “What is most remarkable about Mr Gandhi is his utter dedication and humility. After he came back from Delhi, he quietly slipped back into activist mode and is evangelist-in-chief for the RTI Act,” says senior journalist Sucheta Dalal, the managing editor at Moneylife India, a financial publication and online portal that has organised several RTI workshops with Gandhi.

Gandhi is pleased at the way ordinary citizens have reacted to the RTI, and avers that there were 6 to 8 million applications received last year. Many, he rues, are unnecessary. “A lot of the issues for which we file RTIs are sorted out over the phone in other countries,” he points out. “For instance, if you need to check the status of a ration card application, it is impossible to even think of receiving a rational answer over the phone here. Such issues should be ironed out.”

To get more citizens enthused about in the RTI movement, a part-time certificate course has been started by the University of Mumbai, thanks to Gandhi, who has since approached the NMIMS School of Law in Mumbai to introduce it as a subject in the third-year curriculum. “I am designing the syllabus and setting question papers, which is a very different experience for me. After all, the last question paper I saw was back in 1969!”

While his crusade on the RTI front will continue, Gandhi is currently working on a book that decodes the language of the law to eliminate its misinterpretation. “I want to simply look at the language of the law, without referring to anything else, and interpret what it means. I would also like to present a view and a counterview, and let people decide for themselves.”

Photos courtesy: Shailesh Gandhi Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine July 2016

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….