People

The multitalented, multifaceted M K Raina is impressive on every platform he graces and expressive over every cause he embraces, discovers Irfan Syed

With his twinkling eyes, silver beard and easy demeanour, Maharaj Krishna Raina comes across as the soft-spoken sort. But engage in deeper dialogue with him or talk about causes close to his heart (there are many) and he proves to be outspoken. Raina doesn’t lose his cool—he seems too dignified for that—but ensures his viewpoint comes across resoundingly, using his theatre-cultivated cadence to precise effect.

He is also quite individualistic and a bit of a non-conformist. After passing out of the National School of Drama (NSD) in the early 1970s, with an award for acting no less, he was clear about being only a freelancer—and has remained so ever since. Where does this rebellious streak come from? “My Kashmiri arrogance,” he replies, with a mix of jest and candour.

From his family, MK—as friends and acquaintances call him—also seems to get his activist genes. His father Janki Nath Raina was a renowned political activist of his time. MK’s thespian and creative talents, though, seem to be all his own. Born in a large brood of doctors and engineers, the stage called him early. He acted in a play in Class 5 and was immediately given in to the proscenium. It also helped that he had an encouraging principal, the illustrious poet Dinanath Nadim, or Nadim sahib, as he was popularly known.

Raina joined NSD after college, clear on pursuing direction. But the school and its then director, theatre doyen Ebrahim Alkazi, had other plans for the young man. He was urged to sign up for acting instead, as the direction classes had too many takers and the acting ones too few. He agreed, but resolved that he “would join direction classes when available”. At the hallowed school, Raina handled every aspect of the stage, from lighting to set design. He eventually graduated with a best actor award, but not without a head-versus-heart tussle during his final viva. He had an opportunity to go to Paris on a scholarship but his heart was keen on discovering India. “I hadn’t even seen the Konark temple,” he recalls his frame of mind then. In the end, even after an intervention by Alkazi, he did neither—life again seemed to have other plans.

MK started his career, work and life as an independent artist, which brought him to then Bombay off and on for work. In the city of dreams, he met theatre pole stars P L Deshpande and Vijaya Mehta and luminaries of Hindi art cinema like Kumar Shahani and Mani Kaul. The latter affiliation paved the way for his first film, 27 Down (1974). The film is about a young man caught between the path his father foists on him and forging his own. Raina plays the protagonist, rather unrecognisable with a black beard and full head of hair. Starring Rakhee as his love interest, the film enjoys cult status even now among aficionados of ’70s and ’80s Hindi parallel cinema.

Raina soon found himself being cast in other ‘art’ films, including Mani Kaul’s Satah Se Uthata Aadmi (1980), Kumar Shahani’s Tarang (1984) and Kasba (1991), Mrinal Sen’s Genesis (1986), Buddhadeb Dasgupta’s Andhi Gali, Govind Nihalani’s Aghaat (1985) and Basu Chatterjee’s Ek Ruka Hua Faisla (1986), based on Sidney Lumet’s classic courtroom drama 12 Angry Men. The latter two also star K K Raina—here, this Raina answers an oft-wondered question: no, they are not brothers or even related, just contemporaries, although amicable ones; MKR is older to KKR by a few years.

Raina’s parallel cinema journey hit a roadblock soon after, during the filming of Panchvati (1986), where this theatre maven from Delhi was “made to feel like an outsider” in the Hindi film industry. He was next seen in Bollywood only over a decade later, in Lakshya (2004) and later as the school principal in Taare Zameen Par (2007). After that, as he says, smiling, he appears in a film whenever “they want a daddy”.

In theatre, the recently turned septuagenarian is more of a grand-daddy—and this is neither in reference or deference to his age. He has been the architect of over 200 plays, grand and small, mainstream and experimental, in various languages and locations, including one 12,000 ft above sea-level. His plays have drawn on works of legendary playwrights and writers, such as Bhasa, Brecht, Gorky, Manto, Dharamvir Bharati, Premchand, Bhisham Sahni, and many more.

Coming up, as a part of Mahatma Gandhi’s sesquicentennial celebrations that commenced this October, are four plays on the Mahatma. The first, Stay Yet a While, based on communications between Gandhi and Tagore, was staged on Gandhi Jayanti. The second, Hatya Ek Aakar Ki, debuted a few days later to appreciative reviews. Yes, he is a Gandhian, he declares, as also “the best child of India’s socialism”. He has studied on scholarships, gone to places on fellowships and “has a home in every state”. When travelling for work or workshops, he puts up with friends, family and fraternity.

Gandhian values and principles will no doubt be invoked in a big way over the coming year. But it’s also compelling to ask Raina about Mantoiyat. Both because the writer is being celebrated at present, with the release of his biopic, and owing to the attacks some artists have come under in the past few years, like Manto in his time. Raina is immensely familiar with the beleaguered writer’s work, having staged a play drawing on several of Manto’s stories, and has been his vocal self during the siege on artists. So, (how) is Manto relevant in today’s times? Raina responds with Manto’s famed aphorism: ‘Why do I write? I write on society’s blackboard with a white chalk so that the blackness of the board becomes even more evident.’

Another question about the artistic ethos, this time about Raina himself… if he loves theatre so much, having spent more than half his life here, why didn’t he set up his own theatre company—like so many theatre artists—since he was clear about being on his own? His response is candid: “I didn’t have any back-up.” He adds, though, that he is regularly approached by corporates to help set up theatre companies. He turns down these offers because he knows they are looking for “a shop and not an institution”, which will need to begin showing profits soon; an actual theatre company would “only give dividends in its seventh year”.

This characteristic forthrightness and desire to do the right thing had two distinct triggers, Raina recalls, one coming on the back of the other in the early ’90s.

In 1989, close friend and theatre activist Safdar Hashmi was attacked by political goons during the performance of a street play, succumbing to his injuries the very next day. Hashmi’s death left Raina deeply shaken. Putting his anguish aside, he decided to respond affirmatively. He spearheaded several communal harmony campaigns and marches and also became a founding member of the Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust (SAHMAT), which works to engender creative and cultural expression.

In 1991, insurgency hit his home state Kashmir, forcing him to move his entire clan to Delhi, where he has been living since 1970, after graduating from NSD. The artist may have left his home, but home didn’t seem to leave the artist. Raina was restless. He longed to go back to Kashmir and help in some way. But how?

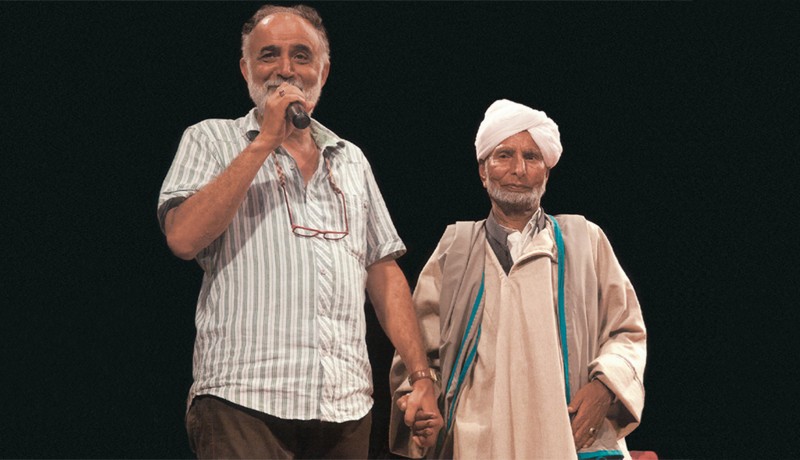

One day, “without thinking”, he left for the valley state. On getting there, he was witness to heartbreaking sights, among people in general but especially among rural artists. The militants hadn’t spared even art. Folk theatre venues had been attacked and their instruments broken. The artists were in deep mourning. But seeing Raina, a familiar face and fellow artist, they felt they had something to hold on to. Raina, too, saw how he could help, through the only way he knew: theatre. Returning to Srinagar, he first started theatre workshops and then initiated collaborations between city actors and their rural counterparts. Eventually, he moved the theatre scene from the city back to the villages. He remembers that when he started the collaborations, a couple of actors from the villages let out painful howls. They had found their release.

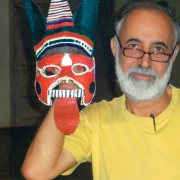

Raina, in addition to other Kashmiri artists, has also helped sustain bandh pather, the local folk theatre where men enact storylines often satirical or farcical in nature, offering a comment on some aspect of social or cultural life.

But Raina is also drawn to causes beyond theatre. Better still, and perhaps owing to his standing and outspokenness in the artistic sphere, the torchbearers of various causes are drawn to him. He is often called upon to speak on issues such as attacks on writers and other creative folk and the need to protect vernacular languages.

The artist-activist is especially close to the latter cause. He is a multi-linguist, knowing tongues as diverse as Bengali, Rajasthani, Dogri, Punjabi, Sanskrit and Urdu apart from Hindi, English and Kashmiri. This aptitude also comes from the fact that he’s directed so many plays in so many different languages.

His love for Urdu is evinced—apart from his knowledge of Manto’s works—from his WhatsApp profile picture, which is his speaker profile for Jashn-e-Rekhta, the annual festival held in Delhi to celebrate the language. And his familiarity with Bengali is evident in his voice, which bears a hint of the rosogolla-laced tongue. That, he says, is because, he’s done some plays in Bengali but also because his better half is half-Bengali.

There seems to be little in the public domain about his family but now that it comes up, Raina is obliging. His wife is a doctor; they have been married for 40 years, bringing up another personal milestone this year apart from turning 70. His son has followed somewhat in his footsteps. A photographer and filmmaker, he has made documentaries on, among other subjects, Sufi music and more notably Zohra Sehgal. Raina himself was acquainted with the feisty and zestful dancer, choreographer and actor, having directed her in a play and film. Raina also has a daughter, who is into public policy.

Personal milestones do not seem to mean much to him. His 70th birthday earlier in the year, he says, “was like any other day”. But on the work front, he seems to have moved toward new horizons.

Three and a Half / Teen aur Aadha is a bilingual (English / Hindi) film about love, longing and loss, told as an anthology of three stories across three time periods, each story filmed in one continuous shot. Due for theatrical release early next year, the story featuring Raina is perhaps the most intriguing. It’s about the relationship and reflections, not all happy, of an older couple, and includes a lovemaking scene or two, going by the trailer.

Was filming it uncomfortable, given that we live in a country and time where dada-dadi and nana-nani are meant to be seen more in a park than in a bedroom? Raina shares that on coming to know the hues of his story, he had put forth the name of his co-star Suhasini Mulay (a shining silver and artist in her own right), as he shared a good rapport with her, having known her for the longest time. It would be easier navigating those scenes with her, you decipher. It seems to have worked.

Raina will also be taking a step into the mainly millennial playground of web series, with Kabir Khan’s upcoming The Forgotten Army, based on Subash Chandra Bose’s Indian National Army.

In between, he regularly features in ads, as the affable senior. Most memorable is the Visa card ad from early last year, which depicts him as a literature professor haplessly seeking change in a post-demonetisation world. He is eventually helped out by a student he took to be a drifter, but not before the actor delivers a few dozen brilliant micro-expressions aptly conveying the plight of the suddenly cashless citizen. Similar themed, but more cheery, are the Amazon Fire TV Stick spots, which present him first as a quizzical granddad learning the use of the device from his granddaughter and then as a savvy senior showing off the powers of the gadget to his grandkids.

How tech-savvy is he in real life? Well, he is on Facebook and uses an iPad to check and respond to emails. He has been learning technology and its benefits, slowly but surely. “How else would we be able to have this interview with you [in Mumbai] and me here, sitting on the footsteps of this room in Bhilai?” he exults.

Plays, films, ads, web series, workshops, tours, talks, causes…. how does he manage to stay fit and healthy for all this? “I lead a straight life. No late nights… helps me have a clear day.” He doesn’t smoke, but enjoys a drink from time to time. Like the elixir of many a silver, he practises yoga, thanks to which he was able to jump into a moving train with alacrity in a scene for The Forgotten Army.

While on matters physical, a trivial question pops up. What explains the bearded look, which he’s sported for over 40 years now and has gradually gone from pepper to salt? “Oh, that is just being too lazy to shave!” And then, “The few times I shaved, I noticed I have dimples… so I stopped!”

Photos courtesy: M K Raina Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine December 2018

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….