People

Artist Lalitha Lajmi’s brushstrokes mirror a life well lived, writes Rachna Virdi

Art often reflects life, more so if the artist is sensitive to her surroundings. One of the best water colourists of India, Lalitha Lajmi’s works are powered by an autobiographical streak, exploring gender politics and highlighting the natural bonding between women, particularly mother and daughter. She experiments with mirrors (reflecting the landscape of the mind), masks (concealing alternate undisclosed identities) and performers (playing out different roles), and uses grey, Prussian blue, black and sepia tones time and again to tell stories rooted in melancholia.

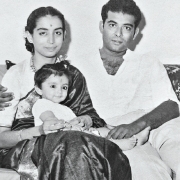

Born in Calcutta, Lajmi grew up around the oleographs of Raja Ravi Varma. Her tryst with paintings, however, began at the age of five when her uncle B B Benegal, a commercial artist, gifted her a box of paints. An early marriage and children didn’t deter the self-taught artist. Modernist K H Ara, who saw her work, encouraged her to display it. Over the decades, her works have been exhibited at prestigious galleries in India, Paris, London and Holland. Lajmi’s works, with their monochromatic effect and melancholic worldview, have often been compared to the films made by her famous sibling Guru Dutt. “We had a disturbed childhood. Economically, too, we were not very sound,” she points out. “So the pathos and subdued style may spring from that.”

A huge poster of Dutt’s classic film Pyaasa at her Lokhandwala home is testimony to the deep influence art and films wield on the family. Besides Dutt, Lajmi’s family boasts filmmakers such as Atmaram (her elder sibling), Shyam Benegal (her cousin) and daughter Kalpana Lajmi. A gigantic bookrack—with a stack of classics, bestsellers and old and new titles—covering an entire wall, reflects the family’s eclectic reading habit. One cannot miss the twinkle in the proud mother’s eyes as Lajmi says, “Kalpana is a voracious reader.” Many books in the collection, especially on art, were gifted by Benegal. Pointing to a section on astronomy and philosophy, she says, “Those belonged to my husband. We bought a lot of books from Strand Book Stall on a monthly instalment of ` 30 in those days.”

While one wall is dedicated to books, the other showcases Lajmi’s paintings. Her women are strong and assertive. “My paintings reflect my life and the crises I faced,” says the soft-spoken artist. Draped in a lavender cotton sari, her bright smile complements the kohl-laden eyes. “I buy my saris from Kolkata,” she shares.

Even before the old-world charm of the place sinks in, the 85 year-old takes us to another room to recount her journey as an artist spanning five-and-a-half decades over a leisurely Konkani Saraswat meal. With effortless ease, she turns gracious host, serving us sambhar along with chana ghassi, parval subzi, rice and kheer.

Along the way, she introduces us to her two female dogs Scooby and Kali, who haven’t left their owner’s side all this while. “This one is old and suffers from arthritis,” she says, pointing to Scooby, while instructing the attendant to take them away for their afternoon nap. After the interview, we get a visual treat of the artist’s studio, where her finished and unfinished works, canvases, colours, paints,

paintbrushes and easel lie quietly, waiting to come alive at the dexterous hands of the artist.

EXCERPTS FROM AN INTERVIEW

In your latest exhibition A Pale View of Hills, the overriding themes are death and melancholy. Are these a reflection of a personal crisis?

I had done some etchings and drawings on death earlier too. I’ve seen many deaths in the family, beginning with my grandmother, father, mother, husband, my brothers Atmaram and Vijay as well as my eldest brother Guru Dutt who died very young. His death at the age of 39 left a deep void in our lives. Besides, death is universal. Also, very few artists like to show death on canvas because it is a part of one’s personal life that one doesn’t wish to share. Moreover, collectors and buyers want to see happy pictures on their walls. I explored death as a theme as I like to express myself. I’m also a pessimist by nature. Kalpana’s ill health has also impacted me—she is suffering from a renal disease and undergoes dialysis, which takes a huge toll on her. I suppose that reflects in my works too.

Despite being self-taught with no formal training, you have carved a niche in art. Please share your journey.

Though I wanted to pursue fine arts, my mother insisted I study commercial art and work simultaneously. I joined a course in commercial art at Sir J J School of Art in Mumbai and looked for a job. I wasn’t lucky in my job search and failed in one of the subjects in the third year. I discontinued the course and got married the very next year. Bitten by the art bug, however, I continued painting at home. In the process, I learnt and explored a lot in art. Some years later, my sailor-husband Gopi Lajmi was on a voyage with J D Gondhalekar, the dean of Sir J J School of Art. After the trip, Gondhalekar came home for dinner, saw my paintings and enquired if I was an artist. My husband replied, ‘No, but she wants to be one.’ He insisted I join the institute. But I felt too shy as I was expecting my second child then. Later on, in the ’80s, I did enrol myself at the college to complete my master’s in teaching.

Like other well-known artists of my generation, I also dreamt of studying and experimenting at Ecole Des Beaux-Arts, the famous school of arts in France, and joined French classes. However, the responsibilities that came with marriage didn’t let it materialise. Interestingly, later on, I was offered the job of a visualiser in an ad agency with a starting salary of ` 1,800, but my mind was attuned to fine arts and I didn’t want to commercialise my work. It has been five-and-a-half decades now. When I look back, I feel everything was destined.

Do you regret getting married at an early age?

Times were different then. In the Saraswat community, the moment a girl turned 16, the family would look for marriage proposals. The first proposal came for me when I was 17. The prospective groom, Gopi Lajmi, then 23, was with the merchant navy, and the youngest captain with the Scindia Shipping Company. He was appearing for his exams then and also sailing between Bombay and Mangalore. We got engaged. Before marriage, I had gone to Calcutta with my uncle for one-and-a-half months and was keen on joining Santiniketan. But my future in-laws were conservative and insisted the wedding take place within a stipulated time. I was forced to return to Mumbai. We got married in December 1952. I kept painting after marriage, but had to give it a break every time my in-laws arrived from Madras.

Where do you draw inspiration for your work?

There is no inspiration in art; it comes from everyday practice. Art is a gift from Goddess Saraswati. However, there are some people who have influenced my life: my mentor K H Ara, cousin Shyam Benegal and German archaeologist Heinz Mode, who bought my first painting. A friend’s wife introduced Mode to me at Jehangir Art Gallery. He asked, ‘Young lady, where can I see your work?’ I stayed behind Taj Hotel in Colaba then, so I took him home. He wanted to buy one of the paintings but I didn’t know what price to quote. I faintly knew Ara was selling his paintings for ` 100, so I quoted the same amount. That’s how my first painting got sold! Mode would visit India every year and I would always give him a painting. He didn’t have much money on him because of the war in Germany, so in return he would send me books by post.

Ara helped initiate your first exhibition. How has he influenced your work?

I met him through my filmmaker brother Atmaram, who had made a film on the Progressive Artists’ Group, to which Ara belonged. I had a huge collection of my paintings at home. After seeing some of my works, Ara said, ‘You should continue painting. I will select some of your paintings for a solo show.’ I began painting seriously in 1961 and he helped me launch my first solo exhibition at Jehangir Art Gallery. Some of my early works may have been influenced by his style. Later, I moved away from that and followed my own style.

While working as an art teacher in a school, you continued painting. How did you strike a balance?

I remember telling my professor Vasant Parab that I wasn’t able to sell my paintings. I expressed a desire to take up a job as I didn’t want to depend on my husband. He suggested I join a short-term teacher’s training course. Even during my teaching days, I kept painting at home.

It was tough to strike a balance between work and art along with managing kids and family but I worked very hard. I did a whole series on relationships during that time in oils and etchings. A lot of people have told me that, that particular period of my work was excellent. Besides painting, I did story illustrations for publications such as The Times of India, Indian Post, Femina and Eve’s Weekly. I also took private tuitions in art during weekends. When I look back, I feel amazed at the way I handled things.

You underwent psychoanalysis for gaining clarity of purpose….

In the early ’80s, I had done two exhibitions of abstract paintings. But there was no sense of direction in my work and I felt completely confused. Someone suggested I go in for a psychoanalysis session. The session gave me clarity and helped me work on my skills. By the mid-’80s, I started focusing on etchings, oils and water colours and never went back to abstract.

You’ve had many solo and group shows. What are the significant highlights of your career?

After meeting theatre legend Ebrahim Alkazi and doing two solo shows with him, I got calls from art galleries in Delhi and Mumbai and things fell in place. I did numerous solo and group shows and showcased my work extensively in prestigious art galleries and museums in various countries including the US and Germany. I also did art camps and travelled a lot in India and abroad. Two of my etchings got selected for the India Festival in 1985 in the US. In those days, there were no art festivals but I got invited to biennales for graphics.

Tell us about your early years of marriage.

Before marriage, my husband was posted on the ship sailing between Colombo and Calcutta and later on, he joined Bombay Port Trust, after which we got married. As a young bride, I was too shy and introverted while my husband had a friendly and gregarious personality. He was the youngest pilot and his European bosses were very fond of him. We got accommodation in a quarter right at the harbour. As a girl coming from a large family in Matunga, it was frightening for me to live in that huge house, especially at night, when I could hear the roar of sea waves. I used to communicate with him through letters; many a time he was sailing and the letters reached after he had moved to another port. Much later, he became the deputy conservator for the harbour and we shifted to Colaba. There, too, we had a massive quarter of 6,000 sq ft and lived a luxurious life. One year before his retirement, he took up another job in Marine Club at Ballard Estate for five years. We lived in Colaba for almost 40 years before shifting to Lokhandwala in Andheri. Though my husband was not involved in my work, he was very encouraging. After retirement, he even accompanied me for my openings and other artists’ exhibitions.

Can you share your journey as a mother?

Kalpana was born when I was 20. She was good at performing arts and participated in dramas and elocution in Hindi and English at school and won prizes. I was always supportive of her. At one point, she was keen on joining the National School of Drama (NSD). Once I took her to a Japanese play by Alkazi. After the play, I met Alkazi backstage and told him Kalpana wanted to do dramatics but I couldn’t afford the fees at NSD. He said, ‘You just send her and don’t worry about the fees. There are scholarships too.’ However, at the last minute, Kalpana backed out. According to her, all those who did theatre had to take up jobs to earn but she wasn’t keen on that. Then, I tried at the Film and Television Institute in Pune, which was then chaired by Girish Karnad, whom I knew. However, Kalpana didn’t join the institute.

She worked with Shyam Benegal as an assistant director, and later went on to make art films such as Ek Pal, Rudaali, Daman, Darmiyaan and Kyon. Kalpana is bright, highly philosophical and unconventional in her attitude and a great follower of Mata Amritanandmayi. She lived with music composer Bhupen Hazarika for many years; they used to travel together wherever he was invited till he passed away in 2011. Devdas, my younger son, joined as a cadet on a ship, taught navigation for many years and worked his way up to become the captain. He’s posted in Greece as the deputy director of North of England (a North Insurance Management Ltd company), and is settled in England with family. His daughter Simran aged 21 years is a lawyer.

What was it like to be raised in a creative family with your father a poet, mother a writer and two of your brothers acclaimed filmmakers?

I was born in a middle-class family. My father was with Burmah Shell Oil Company during the war and my mother, who knew many languages, was a teacher. My father got transferred to Bombay and we all shifted to Matunga. I spent my childhood partly in Calcutta and the formative years in Bombay. I did my schooling at Balak Mandir in Matunga. It was wonderful growing up with four brothers—two older and two younger. Though the only daughter in the family, I wasn’t pampered. On the contrary, there were responsibilities since my mother was working. Right from the age of 10, I cooked, bought vegetables and milk, and looked after my younger brothers. Now, when I look back at 65 years of running a home, I feel my early days made me tough and grounded.

We believe your uncle bought you a box of paints when you were five….

Yes, my uncle gifted me a box of paints and gave a box camera to my brother Guru Dutt. He even enrolled me in a drawing competition on the animation series Pinocchio and Donald Duck, which I won. Looking back, the box of paints was so symbolic. I was destined to become an artist. I also learnt classical music for a short while and gave my first solo performance at the age of eight. I was fond of poetry and classical dance too but my mother didn’t let me pursue dance because of financial constraints. Much later, I learnt dance from my sisters-in-law Geeta [Guru Dutt’s wife] and Nagratna [Atmaram’s wife], who was a Bharatanatyam and Kathak dancer.

Tell us about your bond with Guru Dutt. It is believed you played a part in the romance between Dutt and playback singer Geeta Roy.

Looking back, I feel fortunate to have had Guru Dutt as my eldest brother. Through him, I met all the great poets and film personalities of his time. Also, I have such wonderful memories of going to Eden Gardens for picnics during our childhood. Once, my uncle’s neighbour, who was also a distributor, came along with his wife to the picnic. His wife enthusiastically took some of us kids to one side of the garden to enact a scene with some dialogues. I played saint Dyaneshwar’s brother Nivrutti. Guru Dutt surprised us all by performing a snake charmer’s dance. Probably, a large painting of a snake charmer at my uncle’s place had influenced him; he created the whole dance on his own.

It’s true that I played a part in the romance between Guru Dutt and Geeta. I didn’t know what it really was back then, but I tried to bring them together. I also played a postman and exchanged their love letters. Geeta was a successful singer and my brother was still trying to make it big in films. She visited every day in the evening in a swanky open car and we went out for long drives. She even gifted me a ring, which I still have.

It must have been tough to see your brother face the highs and lows in his life and career.

Guru Dutt was like a father figure. He was elder by seven years, so there wasn’t any open communication between us. He was a man of few words and not the type who sat and talked for hours. However, he always gave his first scripts to my mother and me for reading. He invited us for his film rushes and would ask, ‘Lali, how’s the film? What do you like in it?’ After he joined Prabhat Films in Pune as assistant choreographer and then assistant director, he came to Bombay and got a chance to direct Baazi for Dev Anand’s Navketan Films. Dev Anand and Guru Dutt met in Pune and became very good friends.

Guru Dutt later went on to make path-breaking films such as Pyaasa, Kagaz ke Phool and Chaudhvin ka Chand. His early death came as a huge blow to the family; both my mother and I underwent a lot of trauma. It was an honour to have been invited later as the chief guest by writer Nasreen Munni Kabeer and Mahatma Gandhi’s son Gopal Gandhi for the Guru Dutt Film Festival at Nehru Centre in London and Birmingham in 1994, where I gave an illustrated talk on my works.

Your art uses subdued colours mirroring your brother’s films. Did cinema come into your art?

The melancholy and subdued style may be the outcome of our childhood. Much later, I worked as a graphic artist for Govind Nihalani’s Aghaat and Shashi Kapoor’s New Delhi Times and did a small cameo in Aamir Khan’s film, Taare Zameen Par.

Can you share your experience of working with Aamir Khan?

I had volunteered with spastics earlier during my teaching years. Probably because of that, Aamir Khan considered me for Taare Zameen Par. Once I got a call from his office, asking if I could meet him to discuss a film. At first, I thought they were mistaking me for Kalpana but they insisted on talking to me. The same evening, Aamir called from Panchgani and told me he wanted me to do a guest appearance in his movie. I told him I was a great admirer of his work but wasn’t an actress. His secretary sent flowers and cake for me and later he sent a car to pick me up from Mumbai to Panchgani. I was put up in a hotel and the same evening, Aamir came and told me about the role. I was very reluctant about the dialogues, so he got them removed. This is how I came to be a small part of the movie. Later on, I met him at some events and even called him home for Saraswat food, but he said, ‘Do you know my wife is also a Saraswat!’ Aamir is a gracious film director. Both Aamir and Kiran have bought a lot of my works.

How do awards and accolades make you feel?

Awards are important when you are young. At this age, I don’t feel awards are important. Today, I see young women painters winning international awards and recognition but in our times we never reached that stage.

How has age made a difference to your work?

I work in my studio that is located in the garage of my building. Physically, it’s tough for me to handle the canvasses and frames. I get tired standing for hours at stretch while painting. But my passion keeps me going.

AWARDS & ACHIEVEMENTS

- 1977: Bombay Art Society Award for etching

- 1978: Maharashtra State Art Exhibition Award

- 1979: Bombay Art Society Award for paintings

- 1979-1983: Recipient of Government of India Junior Fellowship

- 1983: ICCR travel grant to Germany

- 1997: ICCR travel grant to Oakland, California

Photo: Haresh Patel Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine September 2018

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….