People

Articulate and informed, Goa Governor and prolific writer Mridula Sinha has an inclusive vision for India, discovers Arati Rajan Menon

Elegant and warm, Goa’s new Governor Mridula Sinha is the picture of simplicity as she welcomes us into her office in Raj Bhavan in the picturesque Dona Paula area. As we start speaking, the many layers to her personality reveal themselves—this prolific writer and activist has a definite, inclusive vision for India, where tradition is not sacrificed at the altar of modernity; where three generations walk together in progress and women are celebrated for their uniqueness; and where social progress goes hand in glove with infrastructural advancement. “As a country, even when we lose our way sometimes, we find ourselves again, find the solutions,” she says. “That’s the great thing about India.”

Her idea of India has been forged through years of service. Born in 1942 in the village of Chhapra Dharampur Yadu in Bihar’s Muzaffarpur district, she was encouraged by her father to pursue her education, a rarity for the times. Her husband—lecturer Ram Kripal Sinha—broadened her intellectual horizons further, encouraging her to complete her master’s in psychology; hone her writing skills, which became apparent at a very young age; and become an educationist. Intellectuals and social activists both, the couple engaged themselves in rural development in Bihar. While her husband entered politics and progressed from the district to the state and eventually national level—he served as a cabinet minister in the Bihar government and minister of state in the Union Government from 1977-79—she began to write extensively, with a focus on community-centred themes and village traditions.

She also intensified her commitment to the country, choosing to focus on social welfare than electoral politics. Indeed, she has served as member of the Delhi Women’s Commission (1996-98), chairperson of the Central Social Welfare Board (1998-2004) and Prabhari (in charge) of the BJP Mahila Morcha, before her appointment as Governor in August 2014. With 46 books to her credit, this mother of four (and member of the BJP’s national executive from 1981-2014) also found time to start a magazine Panchva Stambh (Fifth Pillar), which showcases the role and potential of the voluntary sector in the nation’s progress—her daughter-in-law runs it today while she is still a regular contributor.

So where does she get the time? Her response: “The busiest person always has time, because he knows how to manage it efficiently.” We were privileged enough to share some of that time with the highly articulate governor; here are some excerpts from the conversation:

Your Excellency, you come from a village in Muzaffarpur, Bihar. However, your childhood was anything but typical.

Yes, I come from a small village and a simple family but my childhood was empowered. The credit goes to my father. He was a teacher and was known by everyone in the village as ‘Master’. My mother was known as ‘Masterni’ because she was his wife. But she was illiterate. My father was insistent that I get an education. I was one of three siblings; my sister and brother were much older. Although my elder sister was somewhat educated, my father regretted that he couldn’t educate her more. He didn’t have the capacity. With me, he decided to do things differently.

He sent you to Balika Vidyapeeth, a residential school—what a progressive step for the times!

Everyone in the village gathered to see me go; they just didn’t understand what it was all about. It was an extremely rich environment. I studied the Gita, learnt dance and yoga. We did all the exercises Baba Ramdev teaches today, like pranayama and surya namaskar. We learnt many life skills as well; we were taught to cook, sweep and swab, clean our bathrooms, wash our own clothes.

Did marriage change things?

I was in the second year of college when I got married. I was fortunate that my husband, father-in-law and mother-in-law were equally supportive. I was actually pampered. Nobody expected me to confine myself to housework and cooking; my husband never asked me to cook for him. I was encouraged to study all the time. The entire family has truly had a hand in my success. Even after I became a mother, my mother-in-law, sister-in-law and mother all chipped in to look after the baby and let me study. I just had to feed the baby!

They seemed to have recognised your potential….

Everyone recognised that I was a padhne wali bitiya, a girl who would study. They saw something in me. I was very shy, quiet by temperament. I had no burning ambition. But I suppose there is always an inner voice that spurs you on. Even when I was very young, I would write verse, songs. Later, I wrote my first story in one of my exercise books. My husband, a lecturer and intellectual himself, recognised my talent.

Interestingly, when I graduated, my father wanted me to enrol for my MA. Despite being so liberal, my father-in-law was not very keen as my husband was an MA. He thought man and woman shouldn’t be equal; that it may create problems. I was a little sad but then my husband struck upon the perfect solution. ‘It’s fine,’ he told me. ‘Go ahead and do your MA; I’ll just get a double MA!’ And then he went ahead and did his PhD and said, ‘Now, how can you be equal to me?’!

Your father must have been pleased!

It really was very important for my father that the villagers should know that this girl, one of their own, has finished an MA and become a lecturer. None of the girls in the village had studied so this was an important message to send, that it was indeed possible.

You went on from being a lecturer and educationist to author and activist. How did the transition occur?

Becoming a lecturer gave me great pleasure. But living in a separate city from my husband was difficult. After two to three years, we came back to be together in Muzaffarpur. Nanaji Deshmukh, a great neta of the Jana Sangh, would visit our home. He recommended I start a school to help mould young minds. The result was the Bharatiya Shishu Mandir, which I ran for eight years. It gave me so much joy to shape young minds, teach them our culture and values. Then, my husband entered active politics, becoming an MP and then a minister. When he was a minister I stayed back but later, when he moved to Delhi, he wasn’t keeping too well. It was difficult to leave the school behind but I decided to join him. That’s when I started writing actively.

Your writing has been nothing short of prolific, with 46 books to your credit. Is it fair to say family and community have always been central to your work?

The family is definitely at the core of all my writings. I lay a lot of emphasis on keeping family bonds intact across the generations despite changed circumstances in a changing world.

That is intrinsic to the idea of Harmony-Celebrate Age.

It is very close to my heart too. I have written a lot about elders and their place in society. I say, sangh chale jab teen peedhiyan, chadhe vikas ki sabhi seediyan. [When three generations walk together, they can scale the stairs of progress.] In fact, I wrote a story called Dattak Pita [Adopted Father], which has been made into a film by NFDC [National Film Development Corporation of India]. I have urged people to ‘adopt a father’, ‘adopt a mother’. In my view, elders don’t belong in an old-age home, they belong at home. There’s a question I’ve been asking for years now. When you look at all the flats being made for the middle class by agencies like the DDA or private developers, why are there only two bedrooms? If one is for the couple and one for the children, what about the elders? In one fell swoop, you have destroyed the idea of a joint family. Instead of focusing on old-age homes, the government and institutions should focus on educating people to take care of their elders. I endorse the idea of putting old-age homes and creches together.

How does one go about this?

It needs to be done on so many levels. From the beginning, children have to learn respect for their elders; it won’t come from slogans and speeches. I once organised a painting competition for children on the theme of family—it was astonishing how few children included their grandparents as part of their family.

I’ve also been advocating the concept of premarital counselling to this end. By this I don’t mean sex education but teaching young women and men how to adjust to a new family with their spouse, in-laws; tackling the many problems that will arise over the years. Both girls and boys don’t really know what to expect from marriage; many think marriage is enjoyment. Actually, marriage is a duty. In looking for individual satisfaction, we often forget the larger family picture. What kind of life is it when you only live for yourself? When we were growing up, we never thought we would live apart from our parents. In fact, when we were deciding our son’s marriage, I didn’t choose my daughter-in-law based on her looks or qualifications. I was impressed because she lived in a two-bedroom DDA flat with both her dadi and nani [paternal and maternal grandmothers]. I knew such a family’s values would be different. We shouldn’t lose our values in the name of modernity.

This brings us to another subject close to your heart: women. Today, while the Indian woman is more independent and has broken so many barriers in terms of employment, she is still the target of discrimination and violence. What is your view on this?

There is a definite contradiction in our society. We urgently need to change society’s mindset about women, beginning with how we perceive the girl child. I’ve tried to do this through my writings and social programmes.

Also, let’s look at the idea of equality; equality ke naam pe humne akhara bana diya hai. [We have created a battlefield in the name of equality.] Women are not equal; they are special. On the one hand, they are capable, politically aware citizens, on the other, God has empowered them to perform certain special duties. In my extensive interaction with women across India since 1980, I have always laid emphasis on celebrating the birth of the girl child as Kanya Janmotsav. Discrimination begins when children are born. People celebrate more when boys are born. They make different sweets. In Bihar, there is a special song sung when boys are born; we have undertaken many drives to see that the birth of a girl is feted in a similar way.

We need a lot of social programmes across India to effect this change in mindset and draw once again from our heritage, which teaches us to respect and protect our women. That’s what festivals like Raksha Bandhan are about. Folk songs speak so much about the relationship between brother and sister; when you learn to respect your sister, it should become part of your nature and extend to other women.

Why doesn’t this seem to be happening naturally?

From my perspective as a psychologist, I do feel that there is a lot of resentment among Indian men over the strides women have made. This manifests itself as aggression and violence. There is an inferiority complex among many men. Even husbands who encourage their wives professionally sometimes begin to feel jealous about their success. Have you seen the movie Abhimaan? That’s the subject of the film! It was on TV the other day and my husband and I were watching it.

Do you get much time to yourself? How has your routine changed since becoming governor? Please share a day in your life with us.

My mornings start the same way they always have. I wake up between 5 and 6 am; the only thing that’s different is someone gets hot water for me now! Then, I start writing—it’s my time, the Brahma muhurta, the time when creativity flows. After that, it’s time for my yoga practice and a morning walk, followed by reading the newspaper and discussing issues with my husband. Then, I get ready for the day and all my meetings. A quick nap after lunch is essential; it keeps me fresh till 10 pm. Afternoons are again packed with meetings and social engagements while evenings are relatively relaxed with some TV. I’m not too interested in serials anymore; we watch the news.

How do you perceive your role as a governor?

People say that it is an ornamental post but I believe a governor can do a lot. Most governors are over the age of 70; they have so much experience to share and a lot to contribute to society. While chief ministers are so busy with all the administrative responsibilities of running a state, governors can look at more societal aspects. They don’t need to command or demand, just interact with organisations and participate in a process of change.

Goa is such a culturally rich place with so many festivals, so much harmony. I have been here before as a visitor; now, it is my home and I want to dedicate myself to the people here, their needs and aspirations. We have received such a warm welcome and the people have great expectations from us. Further, as one of the nine original ambassadors of our Honourable Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Swachh Bharat Abhiyan [Campaign Clean India], I plan to organise a host of activities; we have set up a 12-member committee for the path forward. We will look at schools, beaches, colleges, hospitals—it’s not just about going somewhere and cleaning up. It’s about changing attitudes and habits.

Will you still find time to keep writing?

Oh yes! I have written a new novel on Mandodari, Ravana’s wife, and five more books will come in due course. Mandodari was a strong, remarkable woman. A chapter from the book, which is titled Paritapt Lankeshwari [Aggrieved Queen of Lanka], was published in a literary magazine and received tremendous response. People are very eager to read it. It will also be translated in English. Then there’s a book of poetry, articles and columns. I’ll never stop writing—for me, it’s like breathing.

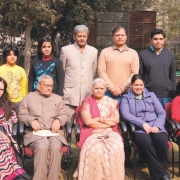

Photos: Aaron De Souza Archival images courtesy: Mridula Sinha Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine December 2014

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….